The Duke of Edinburgh, a New Zealand typist claimed in 1954, was ‘the best investment that the royal family has made in all its history’. But would she have thought so had she seen him a few days earlier at a ‘crazy’ party where, according to his first cousin Pamela Hicks, he ‘excelled himself, managing to use three cracker blowers at once — one in his mouth and one up each nostril, the shiny rolls unravelling simultaneously’?

Anecdotes like that are, I imagine, the chief reason why people buy books like this. Lady Pamela tells them well, especially those about her ancestors. The best-crafted character in the tale is her grandmother, Princess Victoria of Hesse, who was capable of carrying on three conversations in three languages at the same time. Another intriguing lady was her great aunt, who was murdered as a Russian grand duchess by the Bolsheviks but was subsequently resurrected by the Orthodox church as St Elizabeth of Romanova; there is a sculpture of her as a 20th-century martyr above the west door of Westminster Abbey.

One cannot pretend that Daughter of Empire is a book of great substance, and like its predecessor, India Remembered, it seems to have been written under family pressure. Its centrepiece — and the justification for its title — is the author’s account of her time in India, when she accompanied her father Lord Mountbatten during his tumultous months as Britain’s last viceroy. She writes vividly of the atmosphere of Partition, but does not tell us much that we have not already learned from her previous volume.

After India she writes as a participant of such well-known set-pieces as the current queen’s wedding, her coronation and her first commonwealth tour. These are described with charm, geniality and a sense of humour. Like the rest of the book, they give us a flavour of the behaviour and attitudes of a certain class in a certain generation, of people who are ‘thrilled to bits’, who tell the ‘funniest anecdotes’, who are ‘reduced to fits of giggles’ and who love pets and nannies, japes and madcap schemes.

The most interesting parts of the book, however, are Lady Pamela’s memories of her parents. Her father gets off pretty lightly, his viceroyalty exalted, his vanity unpunctured and his conduct as a sailor unexamined. We are told he was so bad a driver that he could overturn his car in a Maltese street, but not that his early naval career was so blighted by mishaps and mistakes that he was known at the Admiralty as ‘the Master of Disaster’.

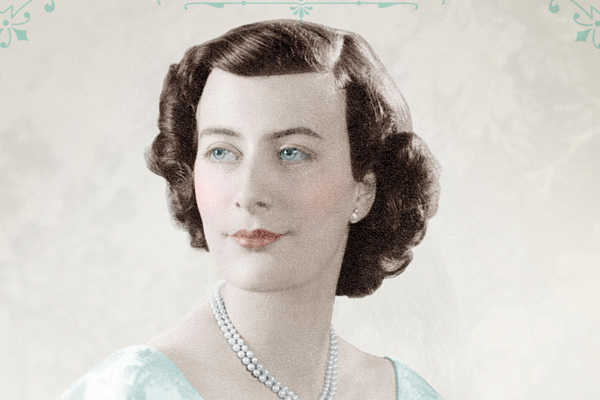

The author’s mother Edwina is treated with less leniency. We are informed early on about her neglect of her children (‘I rarely saw my mother’), her pursuit of pleasure (‘she couldn’t stop herself indulging in this hedonistic way’) and her insensate jealousy when, after years of betrayal, her poor husband found himself a lover of his own. Page after page recounts how Edwina would go off with ‘Bunny’ Phillips for yet another six-month holiday to China or Africa or the Pacific — journeys her daughter can reconstruct from the album in which she stuck endless postcards from Bangkok and Borneo, Hawaii and Sarawak.

Edwina missed birthdays and Christmases; she left her husband alone in Malta, his Christmas dinner consisting of ‘leftovers from the staff lunch’; she abandoned her young daughters with a nanny but no money in a Hungarian mountain hotel and then managed to lose its address. Even when she came home, she was ‘sulky’, ‘brittle’ and ‘very prickly’ unless ‘beloved Bunny’ was at her side. Although her later work in India was a form of redemption for herself, it evidently did little to erase her daughter’s memories of comprehensive neglect.

This is an attractive and generally light-hearted book, but it could have done with some polishing. Although various people are thanked in the acknowledgements, including an editor and a person who brought ‘the book into shape and [made] it readable’, none managed to point out that Spain’s last queen was not called Edna, that Henry V did not address ‘you few, you happy few’, or that overthrowing the Spanish monarchy and setting up the Second Republic was quite the opposite of what General Franco actually did.

Comments