What does superstardom look like? Well, nothing at all. Like anonymity personified. The seriously big celebs, the ones for whom walking down the street is either irksome or potentially hazardous, develop a knack for blending into the background. When Patrick Stewart arrives to meet me at the Young Vic, I scarcely notice him. The jacket and scarf are regulation winterwear. His blue jeans are unexceptional, and his natty trilby is hoiked downwards to conceal his face. Only when he lifts the brim and reaches out to shake my hand does the sonorous magnitude of Sir Patrick coalesce, like magic, before me.

He apologises for arriving 45 seconds late and sits down to sip coffee and eat a chocolate croissant. ‘Bingo,’ he begins. ‘Bingo is a lifelong obsession. Whenever I used to meet theatre producers, here or in the United States, where I lived for 17 years, they’d say, “Is there anything you want to do, Patrick?” And always, always, I would say, “Bingo”. And they’d say, “Bingo, yes. Bingo. Good. What’s that, then?” ’

Bingo is a historical drama by Edward Bond which shows the ageing Shakespeare being tempted by a property speculation which would enrich the local gentry, and himself, and severely impoverish the peasants. Stewart saw John Gielgud play the lead role in London in 1974. ‘The script, as the rare ones do, just stayed in my system.’ It’s a strange title for a Jacobean setting. ‘Yes, there’s a charming rumour that Edward called it Bingo because he wanted to see the word “Bingo” outside the Royal Court.’ Stewart campaigned hard to bring this production, which originated in Chichester in 2010, to the London stage. ‘That puts me under a certain responsibility to do it rather well.’

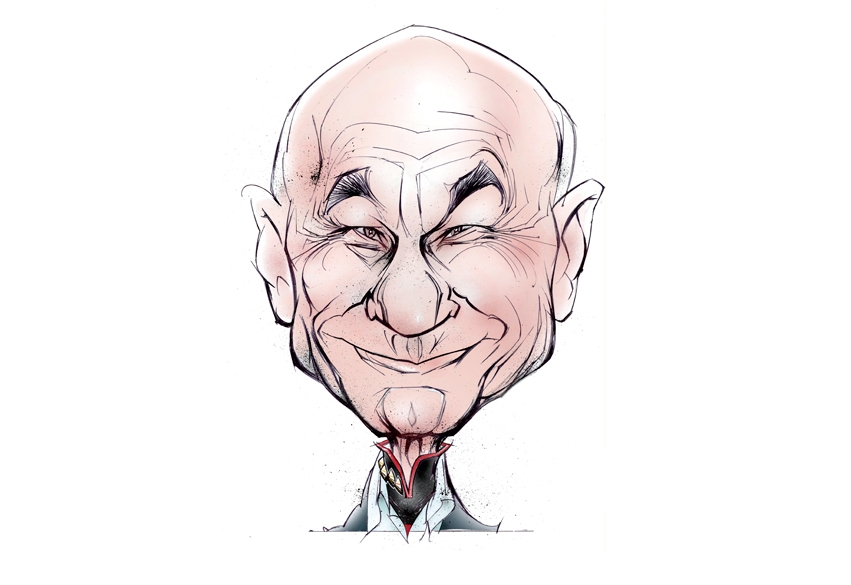

In person, as in the theatre, Stewart exudes a sort of rough-hewn majesty and a certain elusiveness. His voice — dark, richly timbred, mesmeric — suggests an immense range of moods and potentialities. He could be a thug, a womaniser, an emperor, a lunatic, a poet, a lion-tamer, a pontiff, a vagabond, a bouncer, a martyr, a supergrass, a messiah.

And yet something about him doesn’t quite fit. The vocal thunder is an unfakeable gift but the meticulous and percussive exactitude of his Home Counties accent seems almost too good to be true. And there’s the wrinkle. The south of England is alien turf to him. He’s a Dewsbury lad, from a secondary modern school, born in the early years of the war. His mother worked in a weaving mill and his father left the army in 1945 having served as a regimental sergeant-major in the Parachute Regiment.

‘He was brilliant at that job, I’m told. A superstar.’ Stewart pyramids his fingers to indicate his father’s position at the zenith. ‘But like a lot of ex-servicemen he never found the same status again. He was doing semi-skilled work for the rest of his life. It frustrated him and made him often angry and unhappy.’ Stewart’s mother loved her low-paid mill job but the noise and the filth revolted her son. ‘Like one of the circles of hell.’

‘And did you have any expectations as a child?’ He shrugs. ‘Something like that,’ he says, meaning a life of warehouse drudgery. ‘You weren’t planning to become a knight and a global movie star?’ A pause. A slow smile spreads across his lips and a honeyed chuckle rumbles deep in his throat. ‘No-ho ho ho ho ho! They’d have locked me up.’

That his success is an accident, or even a mistake, is a notion that besets him. He’s reluctant to accept the credit for any of his achievements. At school, an English teacher spotted his talent and cast him in productions of Shakespeare. A retired actress living near Sheffield invited him to join the free, informal classes she held for gifted youngsters, among them Brian Blessed. For five years Stewart made the weekly four-hour journey to attend. ‘Very early on she said to me, you have to be able to lose your accent. Acquire RP.’ One of the hardest words, apparently, was ‘war’, which in Dewsbury rhymes with ‘car’. He still has problems with ‘worry’ and ‘hurry’, and their phonetic siblings, ‘curry’ and ‘slurry’. ‘I have to organise my mouth,’ he says and he rattles through them in his posh southern tones. Then he does the Yorkshire version, ‘Wooorry, hoorry, cooorry and sloorry. That’s how I talk when I’m with my family. I revert.’

After training at Bristol Old Vic he joined the RSC and played Shakespeare for 20 years, regularly taking lead roles, without quite becoming a household name. In 1987 he did a series of auditions for Star Trek: The Next Generation. When he learned that the show’s creator, Gene Roddenberry, had ruled him out he was undismayed. ‘I had no interest in it. I looked on the whole thing as a joke but I got these free trips to Los Angeles.’ He landed the part after studio executives lobbied Roddenberry to think again.

Even now he confesses that science fiction holds little appeal. ‘That dismays the fans,’ he adds. Yet he’s happy to show up at Trekkie conventions. ‘In costume?’ I ask gormlessly. A feathery silence follows. And I detect that my question hasn’t quite hit the pleasure button. ‘I don’t show up. I appear,’ he replies softly with the hint of a rebuke. ‘And I don’t wear a costume. They do.’

Good-natured tact governs everything he says about his hard-core votaries — he declines to call them ‘Trekkies’ — and he credits their loyalty with the success of a solo Dickens show he did on Broadway. ‘Nobody wanted to come and see one chap, on his own, in a suit, acting all the characters from A Christmas Carol. So we launched it through the fan clubs. Come and see Jean-Luc Picard. And they did. Filled the theatre for a week. The reviewers followed and we were off and running.’ He has one important reservation about his disciples from deep space. ‘I don’t appreciate people coming in uniform to see me on stage. I’ve made that very clear.’

Seven years ago he left the States and returned to England — ‘the saddest move I ever made’ — to revive a stage career which had evaporated in his absence. ‘Vanished, chyoom, gone!’ But now, having established himself as a West End star, he plans to reverse the process. ‘After Bingo, I’ve a cleared 18 months to investigate the possibility of kick-starting a production career.’ He plans to film a new novel which ‘blessedly came into my hands early on’. Then, tentatively, as if speaking about some weird fluke, he adds, ‘And I’m hoping I shall find my way in front of a camera too, before very long.’

Comments