There is nothing quite like a good centenary to remind us how surprising it is that anyone got out of the 20th century in one piece. In the space of a few weeks this spring will be the 100th anniversaries of the Titanic and Captain Scott’s death, and from then on it’s going to be pretty much downhill all the way — the Balkans in 2013, Sarajevo in 2014, the Armenian massacre in 2015, Jutland and the Somme in 2016, the Russian Revolution, Spanish flu, Amritsar, civil war in Ireland, the rise of the dictators … until before we know where we are it will be 2080 and — light at the end of the tunnel at last — the centenary of the birth of John Terry.

Not every centenary works out quite as expected — the Howards’ medieval tournament at Arundel to celebrate the 600th anniversary of Magna Carta had to be abandoned midway when Major Frederick Howard was killed in a cavalry charge at Waterloo — but one that is unlikely to disappoint is that of the Titanic. From the day the ship went down it seized the world’s imagination, and 100 years of controversy, recrimination and obsessive speculation have done little to suggest that one survivor was too far wrong when he dated the birth of the modern world to the night of 15 April 1912 and the loss of a ship that, till that moment, had seemed to symbolise industrial man’s triumph over the natural world.

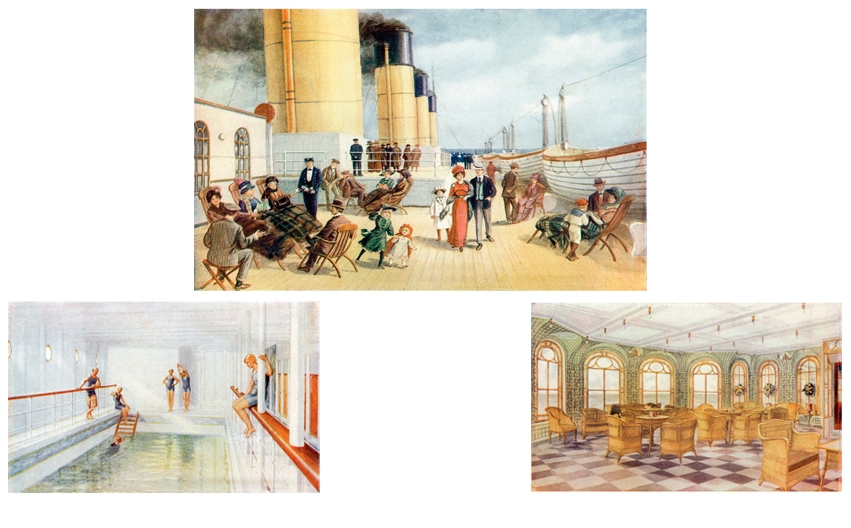

The great thing about ships is that they make ideal symbols, and if symbols tend to end up symbolising whatever people want, there has been a remarkable continuity in the way that generations have seen the Titanic. There may not be many who would join the Bishop of Winchester in seeing God’s vengeance at work, but in its overblown mix of elegance and vulgarity, of extravagant wealth and struggling poverty, of hubristic pride and national navel-gazing, the story of the Titanic still seems a perfect symbol for that endlessly contradictory, self-asserting and self-questioning age that only finally came to an end in the mud of Flanders.

‘It was her first voyage, and she was carrying over a thousand passengers to New York, many of them millionaires,’ wrote Wilfred Scawen Blunt, with a blend of awe, pity and schadenfreude that are still recognisable elements of the abiding fascination of the story:

One thing is consoling in these great disasters, the proof given that Nature is not quite yet the slave of Man, but is able to rise even now in her wrath and destroy him. Also if any large number of human beings could be better spared than another, it would be just those American millionaires with their wealth and insolence.

The other handy thing about the Titanic, as writers from Mark Girouard to the American art historian David Lubin have successfully shown, is that you can say almost anything you like about it and it will probably be true. For a century now authors and filmmakers have used it to explore anything and everything from concepts of masculinity to class divisions, racial stereotyping and anti-Semitism; and Titanic Lives follows suit in the grand style, weaving around the story of one tragic voyage a whole, richly detailed and haunting history of European migration at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries.

The book could, and perhaps should, have been 50 pages shorter, but what ought to go would be hard to say. Henry Harper’s Pekingese, Sun Yat Sen, perhaps, who was rescued in one of the lifeboats? Or Helen Bishop’s lapdog, Frou-frou, bought in Florence on honeymoon? Or the Astors’ Airedale? Or the rare 1598 copy of Bacon’s Essays, which the bibliophile millionaire Harry Widener took down with him? Probably not.

The pity of the Titanic story lies in the detail and it would be as hard to dispense with the few prosaic facts known of a Cornish tin miner or Croatian migrant as it would the more lurid story of Hugh Woolner, one of the first-class passengers who survived. Discrimination would not just be invidious, it would be unhistorical. Ahead of the hundreds of third-class passengers, whose frozen bodies would later be found bobbing in their lifejackets like so many seagulls, had once stretched those same opportunities and hopes that had first brought the Guggenheims and Astors from Europe to America; behind them, in villages across Ireland, Croatia, Syria and southern Greece, they left gaps every bit as desolate as that in the Wideners’ palatial Lynnewood Hall.

This will not be the last book on the Titanic, but it is a safe bet that there will not be a better. It is a grim and harrowing story in its own right, but in Richard Davenport-Hines’s hands it becomes a compelling indictment of the callousness, indignities, greed and exploitation that on both sides of the Atlantic characterised the mass migration of a huge swathe of Europe’s population.

There are the well-known moments of heroism and decency, and contemporaries took what consolation they could out of the Titanic story. It showed how Englishmen could die, the newspapers told them, as they would tell them again a year later, when the news of Scott’s death reached England. It showed, whatever the Bishop of Winchester might preach, that the Anglo-Saxon race was not morally or physically bankrupt. ‘The story is a good one,’ Winston Churchill wrote to his wife.‘The strict observance of the great traditions of the sea towards women & children reflects nothing but honour upon our civilisation.’ He felt ‘proud’, he told her, ‘of our race and its traditions as proved by this event. Boat loads of women & children tossing on the sea — safe & sound — & the rest — silence.’

He was clutching at straws. Faulty design, incompetence, negligence, greed, criminal over-confidence — from shipyard to Atlantic grave, these are the real elements of the Titanic tragedy and the rest is not so much silence as window dressing. Sir Osbert Sitwell was not the only one who looked back on the sinking of the Titanic and saw ‘a symbol of the approaching fate of Western Civilisation’.

Comments