Five clever updates of Old Testament stories filled Radio 3’s late-night speech slot this week and revealed just how difficult it is to make these stories work in a contemporary setting.

Five clever updates of Old Testament stories filled Radio 3’s late-night speech slot this week and revealed just how difficult it is to make these stories work in a contemporary setting. Without the cadences of the Authorised Version, the rigour of the language, its powerful rhetoric but also its inflated poetic style, Noah and his ark, or Samson and Delilah, can appear quite ridiculous.

How do you make sense of miracles in our enlightened times? A young man who works in a B&Q DIY store follows a ‘vision’ and saves his family from a flood in Lewisham by building a boat out of timber he has stolen off the shop floor? Teenage Samson struggles at school because of his exceptional strength, pulling doors off hinges and breaking chairs, and because his mother, a hairdresser, refuses to cut his hair? But New Mystery Plays (produced by Jessica Dromgoole) just about pulled off this sleight of hand, the quality of the writing (by five different playwrights) packing so much into just 15 minutes, a life story told in fewer than 2,000 words.

Sean Buckley’s retelling of the Creation Story was particularly effective, giving us Genesis through the mind of a young woman in a coma. It was a hard listen, and you really had to concentrate to work out what was going on. Jo (played by Alex Tregear) has been unconscious for three years since an accident. Her nurse (Jonathan Forbes) is waiting for a response, a flutter of the eyelids, a twitch in a finger, anything to suggest that something is going on in her mind. We, as listeners, are taken inside that mind, and into Jo’s struggle to get out of her locked-in state. The beginnings of language. The difficulties of communication.

On Broadcasting House this week Paddy O’Connell and his guests were talking about what makes us listen. What makes us really listen to, instead of just half-hearing, the voices of John Humphrys, Rob Cowan, Nicky Campbell or Chris Moyles burbling away in the background. They decided it was something to do with a change in the tone of voice, either in anger or with emotion. Or because if the news has segued into a drama there’s been a clever creation of atmosphere. It’s the sudden switch into an unusual soundscape that grabs our attention.

In Sean Buckley’s short mystery, it was the intriguing use of language which drew me in. And the echoey atmosphere — clinical, nothing soft, all clipped, hard edges — contrasting with the nurse’s rippling stream of conversation as he tries to make some connection with his long-silent patient. Her father arrives and you hear his car drawing up on the gravel outside. Then the clip-clop of his feet as he walks along the hospital corridor. He enters the room, gives Jo a kiss on her cheek, which is flat and unresponsive, no give, no pulsing flesh. No words were necessary to explain where we were or what was happening.

It’s worth listening to all five plays together (now so easy with Radioplayer) as they are all so different, each adding something to this reinterpretation of these ancient explanations for life’s puzzling cruelty. Creation was almost like poetry, in its rhythms and repetitions, the pauses, the sparsity of words needed to convey the relationships between patient and nurse, father and child. Roy Williams’s David and Goliath was poetry in another guise as Asher, Jase and Moe taunt David into sparring with a very modern giant from a rival gang who are trying to invade ‘their postcode’. The language was straight off the bus — ‘Why don’t ya all give ya rubber lips a rest, yeah?’ — but so fast, so interwoven, like a tapestry, as the gang members each tried to stamp their identity, their personality on the group.

Their ‘miracle’ was all-too-believable; a reflection of far too many newspaper reports. Its soundscape, too, was brilliantly effective — pitch-dark, menacing — and created so simply through a barking dog, the sound of glass breaking, or the wail of a police siren in the distance.

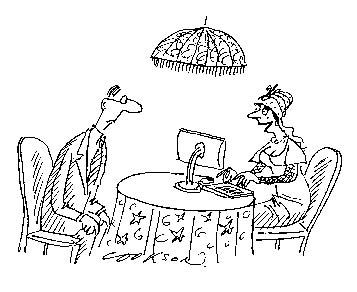

J. Parkes, too, wrestled with a very real life situation in his reimagining of the flight of the Israelites across the Red Sea. In Exodus Moses is translated into Mo, an agency nurse who turns up at a horrid ‘retirement’ home for old ladies run by the dreadful Fay and Helen. You know they don’t care right from the start when the first thing you hear are the keys of a computer relentlessly tapping out a meaningless communication. Fay and Helen spend all their time in the ‘office’ but Mo tries talking to the residents. ‘It’s not the food I mind,’ Miriam tells her over her dish of porridge and prunes. ‘But the sound. The sound of people eating…All those spoons scraping all around…Scraping.’ The hideous reality of life in a badly run home for the elderly was summed up in that one sound.

Comments