Shadow Catchers is an effective title, with its magical and occult associations, and a nice echo of body snatchers into the bargain.

Shadow Catchers is an effective title, with its magical and occult associations, and a nice echo of body snatchers into the bargain. The exhibition (sponsored by Barclays Wealth) it labels is less impressive: a group of five individuals who might be photographers or might be artists showing us their experiments with light-sensitive materials.

Wandering round the more than usually subfusc exhibition space, I wondered whether this was not more properly a display for the Science or Natural History Museums. The dim lighting, apparently dictated by a concern for the durability of these exhibits, confers a reverential if not actively spiritual atmosphere on the proceedings, but could not disguise the fact that here were a load of nature slides and technical adventures. Art has to be more than technological innovation or gimmickry, and in this show the transformation only rarely takes place.

The visitor first encounters the work of the German Floris Neusüss (born 1937), who apparently pioneered the use of life models to make photograms, though I thought Man Ray did that 90 years ago. Anyhow, here are silhouetted female nudes, all looking rather hippy-ish and strongly reminiscent of that flickering flame dance in sexy silhouette that used to grace the opening sequence of the TV adaptation of Roald Dahl’s Tales of the Unexpected. Elsewhere Neusüss shows what he can do to record even more directly the hand of God, by exposing photographic paper to an electrical storm. The lightning was evidently unwilling to conspire — we are shown undramatic scribblings, infantile scratchings on the wall of time, like prehistoric paintings in the cave of memory.

Sorry, I was getting carried away. The tone of the documentary film, profiling each of the five protagonists, must be catching. This film room is the heart and (unwittingly?) the focus of the exhibition: artists doing what some of them do best — talking. With such high-octane competitors, it’s difficult to award first prize for pretentiousness. Better to get back to the exhibits. The work by the mischievous Belgian Pierre Cordier (born 1933) is all pattern-play, geometric-like Arabic tile design, or organic and suggestive, more about texture and depth. The earliest of his ‘chemigrams’ (he uses varnish, wax or oil with the chemistry of photography) is the best here, from 1957, and strangely beguiling. Garry Fabian Miller (born 1957) makes work in which the idea is more interesting than its realisation. ‘Breathing in the Beech Wood’, a set of 81 images of a beach leaf in varying colours, is typical of this. I’m afraid I cannot get excited by his dim and distant work, not even the triple spears of his reeds.

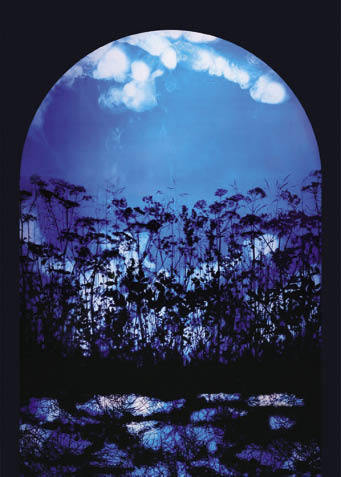

Susan Derges (born 1955) makes poetic statements about a particular place, many of them using water as metaphor. The dissolving and reappearing forms of her River Taw photograms are beautiful and intriguing. Adam Fuss (born 1961) is keen on water snakes and Shaker ladders, a man of the darkroom, not of the light. His ghost images reek of ectoplasmic self-indulgence.

The show is accompanied by a lavish coffee-table hardback book catalogue (Merrell, £39.95), not burdened with too much text and with plenty of juicy reproductions. In fact, looking at the book is nearly as good as visiting the show, though the sense of scale is lacking. At least you can see the photos properly rather than being forced to peer at them through a churchy gloom. It’s rather amusing in this age of digital refinement and ‘anyone-can-be-a-photographer’ that artists using the medium should feel obliged to go right back to its very beginnings in order to try to do something a little bit original or out of the ordinary.

Camera-less techniques were first used in the 1830s when photography was invented, and then enjoyed a resurgence in the 1920s, with Man Ray and Moholy-Nagy. Here they are again for our amusement. Out of the quintet featured here, the only one I can take seriously is Susan Derges: she seems to me to be an artist of real stature.

Upstairs in Gallery 104, should you be able to find your way through the curiously labyrinthine innards of the museum, is a small free display devoted to Edward Gordon Craig (1872–1966). Situated between theatre and rock music, this show has to compete with the distractions of noisy soundtracks, but if you are able to concentrate in the cacophony, your perseverance will be rewarded.

The son of the great actress Ellen Terry and the radical architect Edwin Godwin, EGC trained as an actor before turning to wood engraving and stage design. He is a seminal figure in the theatre, best known for sweeping away the clutter of Victorian productions, discarding gas footlights in favour of electric light from the side and above, and keeping the scenery and sets minimal. He was an inspirational theorist whose influence is still very much felt (the veteran director Peter Brook calls him ‘the origin of it all’), and a printmaker of originality.

The V&A display divides into two sections: the great model of his design for Bach’s St Matthew Passion, which you may sit and study while listening to a commentary about EGC’s life, interspersed with recordings of his own voice; and some 40 wood engravings, woodcuts, etching and wash drawings. William Nicholson taught EGC wood engraving, which enabled him to develop a very particular use of black. His stage designs are all about a sense of space and sky brought into the theatre, as his prints are about light. The etchings of individual stage scenes are particularly effective, but I also liked his series of black figures, his woodcuts from Hamlet and the exquisite ‘Night Sky’ from 1930.

There’s another Gordon Craig show coming to an end at the School of Art Gallery and Museum at the University of Aberystwyth (until 28 January). Organised by Monnow Valley Arts, and accompanied by a useful little catalogue (£10 including postage), this is a selling exhibition of the artist’s exceptionally memorable graphic work.

Comments