How the pursuit of happiness could lead Britain to the right

The political mantra that the Young Turks in the Tory party live by is ‘in opposition you move to the centre, in government you move the centre’. Before the last election, they would

use the line — often a bit defensively — to justify their passive acceptance of Labour policies. But now that the Tories are in power, albeit in coalition, it has become a cry of

triumph.

After seven months in government, the Conservatives can justifiably claim to have moved the political centre ground. The coalition with the Liberal Democrats has ended the prospect of a

Labour-Liberal realignment for a generation. The Lib Dems who are serving in government have come to hate Labour with a passion. It is not political anymore — it’s personal. One senior

Tory recently became confused when a Lib Dem colleague kept saying angrily, ‘it’s what the animals want us to do’. Eventually he ventured to ask who ‘the animals’

were. The answer: Labour MPs.

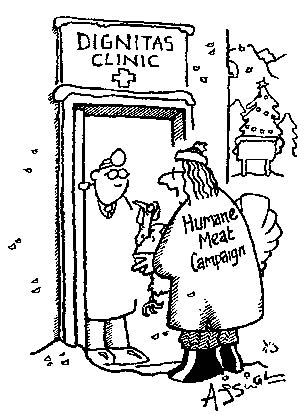

Intriguingly, it is one of their most derided initiatives, the wellbeing index, that will help change the terms of debate. This ‘happiness survey’ makes some in Downing Street very

unhappy. They worry that, at a time when living standards are being squeezed, the initiative makes the government look horribly out of touch. Their great fear is that the index will show that life

isn’t better under the Conservatives, and that it will give the opposition another stick with which to beat them.

Whether Tories see the happiness index as a good or bad thing depends largely on whether they approve of Steve Hilton’s influence on the Prime Minister. Hilton, the chief strategist known for

his ‘blue-sky thinking’, has long been a controversial figure. In opposition, he was behind many of the moves that were designed to ‘detoxify’ the Tory brand, such as David

Cameron’s photo-op with huskies in the snow. Some regard him as a genius; others blame him for the Tory failure to win an overall majority.

Part of the animosity towards Hilton stems from his pointed refusal to behave like a member of the Tory tribe. His failure to dress like they do really does rile some Tories. He routinely walks

around 10 Downing Street in his socks, and during the election was often to be found wearing a T-shirt and shorts at Tory campaign headquarters. Absurdly, his enemies regard Hilton’s casual

dress sense as a sign that he is not a serious figure but an intellectual man-child. He is also, by his own admission, short-tempered. He once startled a senior party figure by calling him a

four-letter word, the same one that recently bedevilled two BBC presenters.

Cameron finds him an invaluable source of inspiration, though. The ideas that have come to define Cameron are Hilton’s. As Michael Gove once put it, when the two men are brainstorming, it is

‘impossible to know where Steve ends and David begins’.

Hilton’s foil within Downing Street is Andy Coulson. A former editor of the News of the World, Coulson is Cameron’s link to Essex man. He has little time for the wellbeing index, and is

worried about the tittering headlines it might inspire. One Cabinet Office source says that ‘the clash between [Hilton and Coulson] is a clash between someone who believes that being

right-wing is about pleasing the Sun and someone who thinks it is about long-term cultural change’.

Coulson has fought a prolonged battle to distance the Prime Minister from the Hilton agenda. But the Prime Minister has overruled him. He really does believe in the importance of general wellbeing.

Cameron believes Hilton’s vision advances values that are intrinsically conservative. He is taken with academic research that suggests that the two biggest factors in human happiness are

employment and family life. The Prime Minister thinks that by making people’s wellbeing into something that must be considered when making policy, he can push future administrations to be

pro-work and pro-family. He believes that Labour’s decision to let five million people stay on out-of-work benefits during the boom would have shown up as a problem in the wellbeing figures

even if it did not feature in the economic statistics.

Another way in which the Tories think they are moving the political centre is by devolving power to the local level. The closer government is to the people, they believe, the smaller it can be.

Advocates of localism argue that it will be impossible for central government to take back the powers that the coalition is giving away. They say that head-teachers who become accustomed to running

their own schools will not hand back control to bureaucrats without a fight. Equally, neighbourhoods that have been given control of their own planning regimes will not easily accept the return of

central interference.

Tory localists think that their reforms go with the grain of the country’s history. They maintain that the last few decades of centralisation — and of massive expansion in the size of

the state — were an exception rather than the rule. It took a war to centralise the government of this country. Barring another struggle for national survival, localist reforms will not be

reversed.

But the most significant way in which the Tories are trying to effect permanent ideological change is through economic reform. Their aim is to grow the private sector while shrinking the public

sector, making the electorate less dependent on state spending and more aware of the burdens imposed on business and job creation by taxation and regulation. This is why the vast majority of the

proposed deficit reduction strategy — some 80 per cent — is coming from spending cuts, not tax increases.

The Office for Budget Responsibility predicts that by the end of this parliament there will be 1.5 million more people working in the private sector and 400,000 fewer in the public sector. This is

the Tories’ opportunity. If George Osborne succeeds in shifting workers from the public sector to the private, he’ll create a country that is more receptive to Conservative ideas and

less invested in state spending. This would move the political centre to the right and the Tories closer to the overall majority that eluded them in May.

Comments