The sea, the sea. Land-lubbers who write or read England’s history omit it from its heart. At least, we have done so since the aeroplane and electric communications reduced the maritime components of warfare and wealth and travel. The popular imagination banishes piracy, Adrian Tinniswood’s subject, to romance and comic-strips. So we are startled by its modern re-emergence as a major hazard and impediment on the African and Indonesian coasts.

That development is much closer to the 17th-century predicaments recounted by Tinninswood than is the swashbuckling glamour of Captain Kidd or Errol Flynn. Then as now, great powers were taunted by seaborne flouters of international law and by their surreptitious political accomplices. The mightiest state of the 16th century, Habsburg Spain, was harried by the privateering at which Elizabeth I connived. England was itself targeted from Ireland, that ‘nursery and storehouse of pirates’. The phrase was Henry Mainwaring’s, an ex-pirate who had slipped across the thin line between piracy and naval service, between crimes that led to the gallows and honoured national duty. He acquired a knighthood, became vice-admiral of a royal fleet that guarded the Narrow Seas against his former associates, and joined Charles I’s court in the civil war.

Then there were the pirates who found shelter in and near the ports of Dunkirk and Ostend and Brest. At peaks of piratical activity, merchant ships would not put out to sea without government convoys. After the execution of Charles I, privateers fought a proxy war between England and France.

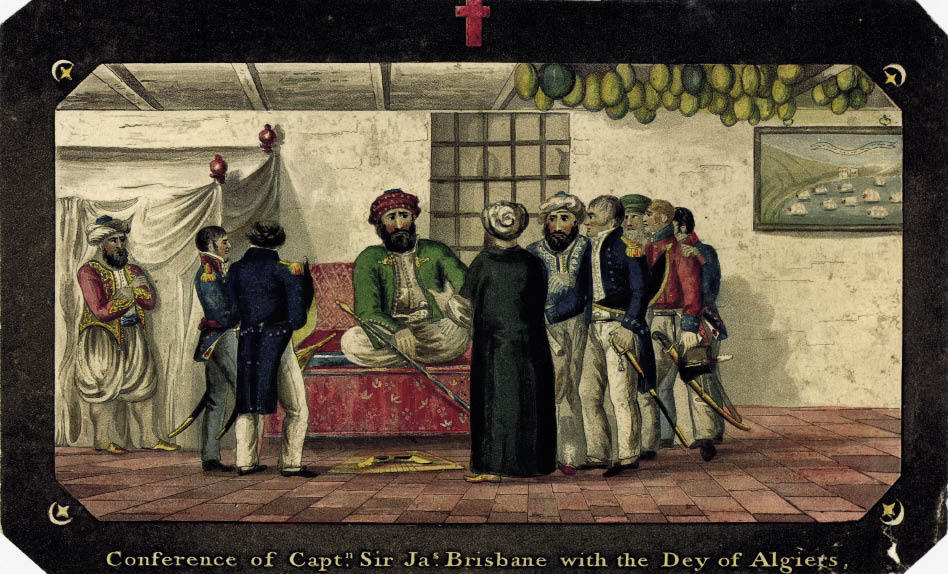

Tinniswood takes us to a larger theatre of piratical enterprise, the coast of Barbary, the 2,000-mile stretch that reached from the Atlantic shores of Morocco, through the Straits of Gibraltar, and along the southern Mediterranean to the Libyan desert. It took in the bases of Salé in Morocco and, east of the Straits, Algiers and Tunis and Tripoli, client states of the Ottoman Empire. Vying for Mediterranean supremacy with Spain and Venice, Istanbul silently welcomed the spoiling of Christian trade and the harrying of Christian coastal settlements. By the early 17th century, commercial expansion had produced giant ships whose rich cargoes offered spectacular prizes. England’s Levant Company, and the officials who taxed it, demanded protection, as its trade and the attacks on it grew. Hatred between Christianity — especially Protestantism — and Islam prompted hideous reprisals. So did the ethnic characterisations attached by the northerners to their ‘Barbarian’ adversaries and by the southerners to the ‘Franks’. Within the Barbary ports the accumulation of booty and the enslavement of captives became a settled industry, with its patterns of investment, its large fortunes, its social customs and rankings. Though most of the piracy was conducted in or close to the Mediterranean, intermittent Moorish expeditions brought dread and hardship to the coasts of the English Channel and Cork and Donegal, or descended on the New World routes. Ships might out-sail their pursuers but could rarely withstand them in pitched battle.

The credibility of England’s rulers was tested and measured by their responses. James I, who hated piracy and renounced the Elizabethan tradition, tried to raise an international fleet to wield ‘the royal sword of justice’ in the Mediterranean, though that pacific and pragmatic king was lured into a policy of amnesty. Charles I, here as elsewhere, was tougher than his father. Having used the public anxiety about piracy to help justify the levy of ship money, he sent a successful expedition under William Rainborow, a senior naval figure, against the Salé corsairs. State propaganda made the most of such strikes. Rainborow’s exploits were hailed in a court masque extravagantly designed by Inigo Jones. Under Oliver Cromwell the burning of the Tunisian fleet by Admiral Blake was comparably applauded, albeit in execrable verse.

Yet naval triumphs, though they allayed the problem, could not solve it. The peace treaties they extracted did not hold. Charles II established a base at Tangier, but had to evacuate it, and was powerless to prevent his consuls from being killed or kept hostage. The eventual solution was a form of institutionalised ransom, which left the corsairs free to assail the ships of other nations, though the system broke down during the American War of Independence and the Napoleonic conflicts. By the 19th century the British navy could more easily enforce its will, but it was only in the 20th, with the takeover of Barbary states by France, Spain and Italy, that the corsair tradition succumbed.

Tinniswood’s artful blend of narrative and analysis brings the pirates’ society to life. He does equal service to the victims and captives and to the ‘stench of brimstone and sweat and fear’ as passengers awaited attack. Beneath the vivid surface of his book there lie, sometimes obscured by the vividness, the careful investigation and astute judgement of one of the most incisive of our popular historians.

Comments