Where to begin? Graham Robb, like all dedicated Francophiles, begins early, when his enlightened parents made him a present of a trip to Paris and sent him off with a map and a voucher for a free gift at the Galeries Lafayette. For a week, and then two weeks, and then six months, he did what all visitors do: he walked the length of the city, he bought books, he sat in cafés and listened to the conversations of strangers. This apprenticeship made him the historian and biographer he is today, and this book is a form of homage to Paris and to those who choose to see it as their home.

To adapt Simone de Beauvoir’s dictum, one is not born a Parisian, one becomes one. Many of the characters in this chronicle were not born in Paris: all they had in common was the language and the agility that denotes the true Frenchman. As of right, Robb’s survey, which runs from the 18th century to the present day, begins with Napoleon, as a young lieutenant, lodging at the Hotel de Cherbourg and enjoying the freedom of the Palais Royal. It is arguably Napoleon who is the tutelary genius of Paris, and whose vision of the world without ambiguities was responsible, many years after his death, for Baron Haussmann’s great boulevards which replaced the secretive streets so conducive to conspiracy and violence.

This is the method that informs the book, to twin a personality with an architectural construct, a person with a place. Thus a topical history is established in which people and places play an equal part. This makes for an ever-expanding canvas in which the author is completely at ease, although the reader may protest at the proliferation of anecdote, rather like a novice arriving in the city for the first time.

This is apposite, since Paris was originally a city without maps, so that, on her escape from the Tuileries, Marie-Antoinette instructed her coachman to take the wrong turning, but nevertheless ended up in the Place de la Révolution, as she was destined to do. Through the various narratives that make up Robb’s book, the largely unsung heroes are the mapmakers, whose feats of observation are truly extraordinary. With a map, had such a thing existed, Marie-Antoinette could have joined the King and perhaps have survived a little longer.

Not all the names in this chronicle are so well known; indeed many of them, dredged from police files, are obscure. Crimes, faithfully recorded, are left unsolved. The real story, it seemed to be agreed, was in the foreground. Thirty years after the death of Napoleon, the city was taking shape, losing its connection with the semi-rural hinterland and becoming professional. Even the police force, benefitting from the example of Vidocq, was becoming professional, although Vidocq was more thief-catcher than agent of the law. Like many of the characters in Robb’s account he enjoyed semi-mythological status, although the Sûreté was to become a powerful institution.

The mythology, or mythologising, of Paris was furthered by Henri Murger’s collection of loosely related stories, La Vie de Bohème, which engendered so may useful fantasies and enhanced the status of the Latin Quarter. Indeed by the midddle of the 19th century it was possible to descry the face of modern Paris. The newly invented art of photography played its part, particularly in the role of advertising. ‘Immense nausée des affiches’, Baudelaire recorded in his notebook, anticipating his own invention, ‘the Heroism of Modern Life’. Modernity, of a triumphant sort, was the gift of Baron Haussmann, who transformed the crooked streets into a symmetry that has never dated and rarely been improved upon.

The very real hero of modern life was Zola, whose novels have undeservedly faded in reputation as his journalism has taken on a unique lustre. Robb chooses to tell Zola’s story from his wife, Alexandrine’s point of view, and her no less heroic stature is made abundantly clear. Zola’s death — suffocation from a blocked chimney — was undoubtedly murder, engineered by those who had cause to fear him (J’accuse), and interestingly has never received official recognition. After his death, it was Alexandrine who consoled his mistress, Jeanne Rozerot, and who took a worthy and protective interest in Zola’s two illegitimate children.

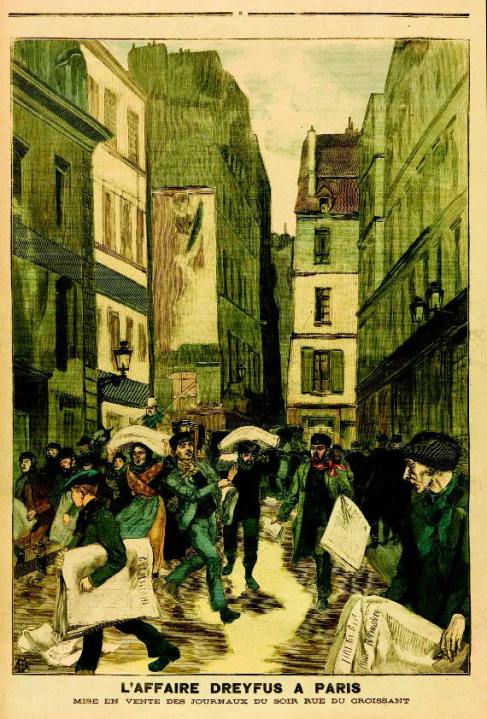

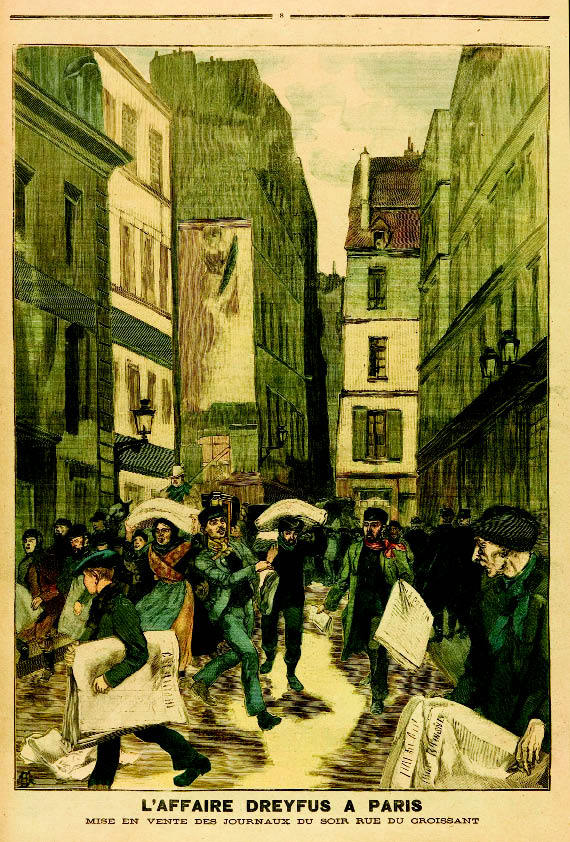

This was an epic moment of human behaviour (‘un moment de la conscience humaine’), according to Anatole France, and it is dealt with by Robb with the respect it deserves. Perhaps the high moral tone could not be sustained. Certainly the legacy of the Dreyfus affair, which so inspired Zola, lived on and was revived in the second world war. Unfortunately, by that time there was no Zola to accuse or to demand an answer (J’attends).

The Zola episode is at the heart of Robb’s book, and its transparency is a welcome oasis in a narrative which is, if anything, too full of matter. One might have echoed Talleyrand’s advice to enthusiasts of all kind, ‘Surtout, pas trop de zèle’. Yet the brief account of Zola’s all-but state funeral, every detail of which was organised by his widow, makes its point by virtue of its brevity — after which a return to the author’s normal rhythm is entirely acceptable.

The Paris we all know, or think we know, came into being with the arrival of the Métro, much admired by Proust, who never used it. This was followed a few years later by the telephone (Proust’s number was 29205). The Paris we can remember, or think we can remember, was the Paris of the 1950s and 1960s, when Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir held court at the Flore, and when a new novel by Simenon appeared regularly every few months.

These were the last of the glory days, when it was possible to feel like a provincial, newly arrived, and undergoing a longed-for transformation, much as Robb, armed with his map and his gift voucher must have felt at the start of his own apprenticeship. New Paris, the Paris of today, is part of Europe, and its concerns are global. The charms of discovery must yield to a different kind of loyalty, to the planet, to the environment. The true Parisian will, of course, shrug this off, and remain embedded in his quartier, will be on polite if not cordial terms with his or her neighbours, and will continue to dress with an eye to fashion. At the same time, the true provincial will still be able to walk from one end of the city to the other, listen to the café conversations of strangers, and admire Baron Haussmann’s accomodating boulevards.

This absorbing book has been ill-served by its publisher, the normally reliable Picador: wrong format, meagre illustrations, inadequate map — although nothing short of a gazeteer could do justice to all the street names mentioned by Robb. If his love of the picturesque detail threatens to overwhelm the reader, the book is nevertheless an act of homage on the part of the author, whose initial visit lies at the heart of his exploration — even if we never find out what he got in exchange for his gift-voucher at the Galeries Lafayette.

Comments