In his preface to The Joy of Gay Sex (revised and expanded third edition), Edmund White praises the ‘kinkier’ aspects of homo-erotic life. Practical advice is given on frottage, spanking, sixty-nining, cruising, blowjobs, fisting, rimming and three-ways. Of course, Proust-inspired poetic exaltations to homosexual love have long characterised White’s fiction, from A Boy’s Own Story to Hotel de Dream. Yet White is no mere popinjay in thrall to high-flown campery; his mind is drawn to some very dark places.

Between 1983 and 1999, as an ardent Francophile, White elected to live in Paris. His chatty, salacious account of those years, Inside a Pearl, dilates knowledgeably on the gorgeousness of the ephebes to be found along the Seine; but the book is also a serious guide to the city’s gastronomy, literature and social customs. If White has nothing much to say on French wines (he is a teetotaller and reformed alcoholic), he does know his restaurants.

In 1956, at his boarding school near Detroit, White had read the firebrand French poet Arthur Rimbaud after lights out. Miserably unhappy, he longed to run away to New York and succeed as a writer; Rimbaud’s poetry, with its hymn to the world as an open highway, fired him to do so. Inevitably, with his drunken outcast legend, Rimbaud inspires hero-worship. I wrote a dreadful play about him while at Cambridge in the 1980s, with Tilda Swinton in the role of Rimbaud’s mother, which was peevishly reviewed by Andrew Marr for the Scotsman (‘This interpretation of the fine poet and darling of teenage depressives will do no good at all’).

Here, White combines the scholarship of his biographies of Rimbaud, Proust and Jean Genet with personal memoir. The result is an exquisitely written work which admirably captures the heady mix of the sensual, luxurious, snobbish and plain small-mindedness that is Paris today, and always was Paris. Tittle-tattle and score-settling colour almost every page. Mary McCarthy in her Paris exile was ‘always cross, as if permanently enduring a bad hangover’. Germaine Greer, irritatingly for White, attacked his Rimbaud biography for its supposed advocacy of anal sex, ‘which she, for one, was categorically opposed to’. (Clearly Greer had not read The Joy of Gay Sex).

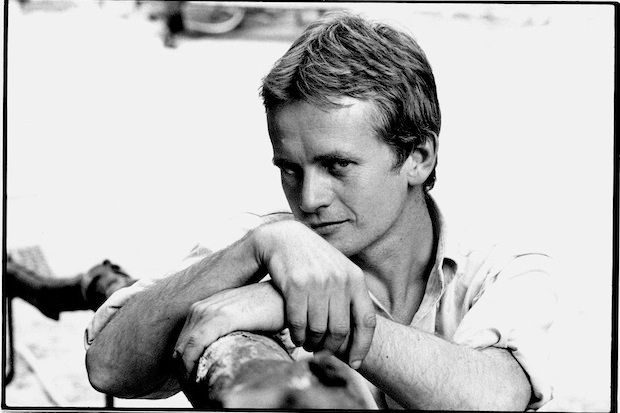

The memoir is engorged (definitely the right word) with homosexual adventure. If Bruce Chatwin was not especially interesting to look at (the photographer Eve Arnold said he was too boyish for real elegance or style), he did have seductive periwinkle-blue eyes. White says that the first time he met Chatwin, they had ‘sex immediately, standing by the front door, half undressed… Every time I saw Bruce after that, usually while we were dining in an expensive Paris restaurant, I’d recall us sniffing each other’s genitals like dogs’. (This is very, very naughté.)

In his last years, White reminds us, Chatwin spread the rumour of his fatal bone-marrow disease; the cause, apparently, was a dubious slice of raw Cantonese whale. Or was it a rotten 1,000-year-old Chinese egg? Only friends, White among them, knew he had Aids. Inside a Pearl is, among other things, an elegy to those legions of writers and artists who died of the virus back in the 1980s.

By his own account, White left New York for Paris at the age of 43 partly to escape the ravages of Aids. But the epidemic caught up with him, and casual sex fostered the voraciousness of the virus; White, who claims to have slept with ‘some 3,000 men’, has been HIV-positive since 1985 but is a lucky ‘slow progressor’. Now in his mid-seventies, he looks well enough.

His 15-year exile in Paris was enlivened, he says, by his friendship with Marie-Claude de Brunhoff, who for many years was the wife of the wealthy son of the creator of Babar the Elephant. In her outré stylish clothes, MC (as White calls her) was a paradigm Parisienne, who wined, dined and collected ‘interesting’ people, several of whom subsequently died of Aids.

Always lively, Inside a Pearl is not without its faults and fallacies (I almost wrote ‘phalluses’ — which would be so wrong). The actress Arletty, having been imprisoned in 1945 for consorting with a German officer, protested indignantly: ‘My heart belongs to France, but my fanny [cul] is mine’; White, perhaps with homosexual sex on the brain, translates cul as ‘ass’, which is not exactly wrong; but Arletty, being heterosexual, surely intended vagina. Perhaps I don’t know the Parisians well enough. One of my favourite French actresses is called Fanny Ardant.

Comments