I suspect I am not alone in finding it surprising to encounter at the close of this exhibition an unexpected Hannah Höch — a gently spoken elderly lady filmed wandering among the overgrown flowers in her garden, talking of beauty. A far cry from the radical firebrand and Dada collagiste of interwar Berlin whose works epitomised the edgy fragmentation of Weimar life and culture. It was a long journey, and one traced with admirable even-handedness by this first and welcome UK survey of Höch’s works on paper, at the Whitechapel.

Hannah Höch arrived in a Berlin teetering on the brink of the first world war, a student of applied arts whose avid curiosity about modernism quickly led her into friendships with Kurt Schwitters, Hans Arp and other artists of the Dada undergrowth. Her day job as pattern designer for the Ullstein Press and its women’s magazines exploited her natural flair for composition, but the demands of decoration were not going to sustain her restless spirit for long. By 1918 she had issued a ‘manifesto’ of embroidery, urging modern women to produce art that acted ‘on behalf of the spirit and changing values of a generation’, and she set out to lead by example.

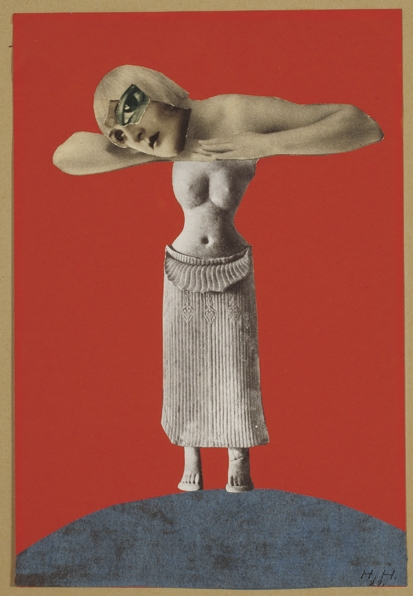

Postwar Berlin was a city reeling in defeat, former certainties blown apart amid the accelerating modernity of the Weimar Republic. The Berlin Dada circle, more serious than their Zurich counterparts, set out to challenge the system on every front. Embracing the blizzard of photographic imagery in the new age of mass reproduction, they took up scissors like scalpels, eviscerating the icons of the past and creating novel and unsettling images from collage and photomontage. ‘They swap heads in photographs, cropping and redefining things, and have developed a technique filled with uncanny suspense’, a review of The First International Dada Fair of 1920 observed, singling out Höch’s work (along with that of her lover Raoul Hausmann and George Grosz) as ‘exceptional’ and well worth the detour.

Comments

Join the debate for just $5 for 3 months

Be part of the conversation with other Spectator readers by getting your first three months for $5.

UNLOCK ACCESS Just $5 for 3 monthsAlready a subscriber? Log in