As if the Church of England didn’t have enough to worry about with leaky roofs, empty churches and lack of money to pay priests, it now has the Archbishops’ Commission for Racial Justice, or ACRJ. Appointed a year ago, this group of twelve of the great and good, under ex-Labour Cabinet minister Paul Boateng, has just published its first report. This document is certainly full of good intentions. Whether it has much to offer the ordinary churchgoer, or for that matter the Church of England as a whole, is rather more doubtful.

Go into any church this Sunday, and it’s a racing certainty that you won’t find much old-fashioned racism. The caricature of the blue-rinsed pearl-clutcher or retired colonel who can’t stand black people is as outdated as a character from an Evelyn Waugh novel: so too the priest who regards Africans or Indians as inferiors to be civilised by white preachers. These days congregations and celebrants alike welcome any worshipper they can get. They have far better things to do than worry about anyone’s origin or skin colour.

It is difficult to see much in the report that is specifically Christian

But that’s not how the ACRJ looks at things. Racism it sees, in a postmodern way, in terms not of individual thought or volition but of social structure: a miasmatic universal presence demonstrated infallibly by a lack of non-white bishops, or churchwardens, writers on ordinands’ reading-lists, or whatever. Rather as St John tells us that if we say we have no sin we deceive ourselves, the fact that we scrupulously try to avoid avoid discriminating on racial grounds does not mean we are not racist, but simply that we do not know that we are. The report reflects this view almost throughout. Even if we don’t notice racism, it is there, and our job is to find it: as we are told (though as a matter of dogma rather than evidence): ‘Racism, past and present, permeates the Church and the world.’

No doubt this is why the measures the ACRJ demands are, to say the least, drastic. On theology and liturgy, for example, the Church’s job is to root out frameworks which have ‘legitimised racism’ and replace them with ‘alternative theological paradigms’ that don’t. The Church’s liturgy must ‘work for and express the transformation from racism to which we believe God is leading us’ and ‘give voice to the breadth of England’s contemporary vernaculars.’ (Details of what this all means are rather lacking, but let that pass).

So too with ecclesiastical administration. Diversity and inclusion ‘need to be woven into the institutional fabric of the Church and its funding processes.’ Big money – something like £20 million, which could pay for a good many desperately-needed priests – needs to be diverted to racial justice efforts, for which the central church administration must have at least three full-time administrators to form a ‘racial justice directorate.’ ‘Grassroots minority ethnic networks’ need to be developed, as does a ‘theological framework for Racial Justice to be used by church schools throughout England.’ Parents, you have been warned.

And that is before we even get to slavery. Here we reach the heavy stuff. The church must actively think in terms of reparations, setting up memorials to victims, and (of course) consider carefully who is commemorated in monuments. Does shielding people from memorials to obscure gentlemen who are unknown to anyone other than historians make the church more welcoming? That seems unlikely.

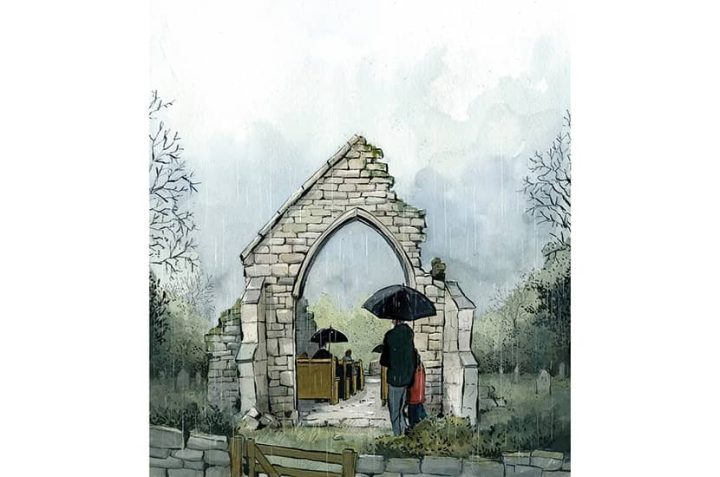

So what are we to make of these developments? One thing is that (at least as regards monuments to slavers) the ACRJ is coming eerily to resemble Cromwell’s puritan iconoclastic enforcers. Their targets may be different: memorials to squires with what we now see as flawed morals aren’t the same as monuments to the Virgin Mary. But the self-righteousness of both groups, and their insistence that their views must be imposed from the top, whatever the local church authorities may think, have a good deal in common.

More interestingly, however, it is difficult to see much here that is specifically Christian. Scrape away the frequent references to the Biblical commands to love one another, and this is is actually a remarkably secular document. Our Christian duty is personally to avoid treating people as less deserving of Christ’s (and hence our) love because of their race. Demanding changes to social or church structures in the name of abstract racial equality, or liturgy or theology aimed at emphasising the contributions of one or more ethnic groups, may be a good thing. But this is worldly politics writ large: demanding the Church adopt it is to subordinate the sacred to the secular.

When it comes to memorials to those involved in the slave trade, the matter goes much further. Traditionally we are taught that we are all sinners, and that any sin, however heinous, can be forgiven. That goes for slave traders too. The demand that special measures be taken to remove their representations from the sight of worshippers, of any colour, comes close to denying this. Perhaps most disconcerting is that the ACRJ seem quite happy with such a view. Indeed at one point its mask breaks down, and it explicitly sympathises with a statement that the church’s attitude to history is wrong precisely because it tries ‘not to find ways of helping Black people deal with the harm done to them by slavery over generations but to get them to forgive the slave traders’. Wow. Some of us might have thought this was what Christianity was all about. But then perhaps the ACRJ, who are much more highly-qualified than we are, know something the rest of us don’t.

Comments