Manet’s paintings were regularly rejected by the Salon, yet he continued to submit them and declined to exhibit with the Impressionists, who regarded him as a father figure. Even when his works were accepted by the Salon, they were routinely received with outrage among both critics and the public. This response baffled him.

When his ‘Olympia’ was shown at the Salon in 1865, along with his ‘Jesus Mocked by the Soldiers’, Edouard Manet wrote to Baudelaire in exile in Brussels: ‘I wish I could have your sound judgment on my pictures, because all this uproar is upsetting, and obviously someone must be wrong.’ And to Antonin Proust he said: ‘Only a fool could think I’m out to create a sensation.’

Ironically, although during his lifetime Manet was considered by many to be a dangerous radical, no artist manifested a greater reverence for the Old Masters. The influence of Spanish art on his work, especially of Velázquez and Goya, was recognised at the time — unsurprisingly, given the explicit Spanish scenes in his oeuvre.

The role of Italian Renaissance art in Manet’s painting has received less attention, despite the fact that Italian works provided the direct inspiration for the artist’s two most controversial, now most celebrated, paintings: ‘Déjeuner sur l’herbe’ and ‘Olympia’.

In 1850, at the age of 18, Manet began a rigorous, six-year-long traditional training in the Paris studio of Thomas Couture, a devotee of Venetian painting. In the same year Manet registered as a copyist at the Louvre, a collection rich in Italian art. In 1853 he made his first trip to Venice and Florence. He returned to Venice again, with his wife and a fellow-artist, James Tissot, in 1874.

The first room of the fascinating Manet: The Return to Venice, at the Doge’s Palace, curated by Stéphane Guégan and designed by Daniela Ferretti with her customary panache, presents key pieces from the archive of drawings and paintings from Italian art that Manet built up in Paris and during his visits to the peninsula. These include sketches of works by Ghirlandaio, Parmigianino, Luca della Robbia, Fra Bartolomeo, Andrea del Sarto and Veronese. There is a detailed oil rendering of Titian’s ‘Pardo Venus’ and a painstaking copy of Tintoretto’s late self-portrait.

Here, too, are the copy in ink of the ‘Concert Champêtre’ (then attributed to Giorgione, but now believed to be partly or wholly by Titian) by Henri Fantin-Latour that Manet had in his studio, and Marcantonio Raimondi’s engraving after Raphael of ‘The Judgment of Paris’. Manet drew on both these works for his ‘Déjeuner sur l’herbe’, which provoked a critical storm when exhibited in 1863 at the Salon des Réfusés. Often described as the first modern painting, it is represented here by the oil sketch version from the Courtauld.

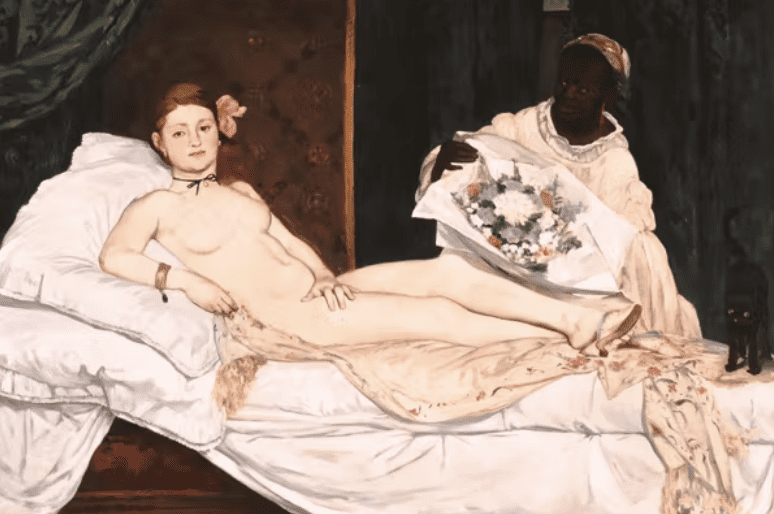

Manet copied Titian’s ‘Venus of Urbino’ when he was in Florence in 1857. And the extent to which he transformed modern art by returning to and reinterpreting the art of the Renaissance is demonstrated in spectacular fashion in the second room of the exhibition where, for the first time, Titian’s ‘Venus’ and Manet’s ‘Olympia’ (which has never before been allowed to leave France) are shown side by side.

‘Venus’ was painted for Guidobaldo II della Rovere, Duke of Urbino in 1538 and taken to the Uffizi in Florence in 1631. The identity of the model remains a matter of speculation, but her facial features bear a striking resemblance to the clothed subject of another Titian painting, ‘La Bella’. Although not the first Renaissance nude that dispensed with mythological or biblical justifications, its blatant erotic intentions meant that for a long time it was shown only to privileged visitors even after the Uffizi was opened to the public.

Manet’s painting is almost identical in size and the juxtaposition of the two canvases reveals how minutely Manet had studied Titian’s image, as can be seen, for example, in his rendering of the pillows and folds of the sheets, and in the enormous care he took to reproduce the rich colours of Titian’s ruby-red mattress and dark-green hangings.

Victorine Meurent, a professional model, who had already appeared as the principal nude in ‘Déjeuner sur l’herbe’, again posed for this picture. Few seemed to doubt that ‘Olympia’ represented a contemporary demi-mondaine, Mallarmé calling her a ‘wan, wasted courtesan’.

We know from contemporary accounts that Titian painted his nudes from live models, but in the case of this Venus there can be little doubt that he idealised and elongated his model’s form in the light of classical statuary and added an element of coyness in the angle of her head and slight blush on her cheeks.

Manet, too, habitually painted from life. ‘I can’t do anything without the model,’ he told his friend and supporter Zola and, on another occasion, he remarked to Antonin Proust: ‘I interpret what I see as straightforwardly as possible. “Olympia” is a case in point.’ Thus it was perhaps above all the challengingly realistic depiction of Victorine’s body, combined with her unwavering, although in many ways supremely ambiguous, gaze that so offended contemporary tastes.

The manner in which Manet combined elements of Italian Renaissance compositions with his own brand of realism is further explored in the rest of the exhibition.

‘Jesus Mocked by the Soldiers’ draws on Titian’s ‘Christ Crowned with Thorns’ at the Louvre, on Andrea del Sarto’s frescoes at the Annunziata church in Florence and on ‘The Dead Christ Supported by an Angel’ by Antonello da Messina in Venice. And Manet’s ‘The Balcony’ appears to owe as much to Carpaccio’s ‘Two Venetian Ladies’ as it does to Goya’s ‘Majas on a Balcony’, not least in the strange distracted air of the female protagonists.

No less thought-provoking are the placing together of Manet’s ‘Masked Ball at the Opera’ (1873–4) and Francesco Guardi’s ‘The Ridotto at Palazzo Dandolo at San Moisè’, and the artist’s ‘Portrait of Emile Zola’ (1868) and Lorenzo Lotto’s ‘Portrait of a Young Man in his Studio’ (around 1530). And in ‘Sur la plage’ of 1873, the composition of the figures, although reversed, is clearly derived from a scene in Andrea del Sarto’s frescoes in Florence, that Manet sketched in 1857.

Manet did not paint Venice itself until his return in the winter of 1874, when he made two oils of the Grand Canal, one of which, from a private collection, is on display here. Unusually, the canvas shows a marked affinity to Monet’s work of this period.

The Impressionist had irritated Manet at the Salon of 1865, when Manet asked: ‘Who is this Monet whose name sounds just like mine and who is taking advantage of my renown?’ But Manet came to admire the younger artist — describing him as ‘the Raphael of water’ — and they even painted together at Argenteuil on the banks of the Seine in the summer of 1874.

Comments