The arrest of a reporter who held up a poster during a Russian news broadcast criticising the war in Ukraine reminds us how dictatorships operate. One of Vladimir Putin’s first acts on the home front, after sending his tanks over the Ukrainian border, was to pass a law specifying jail terms of up to 15 years for anyone who dares to disseminate ‘fake news’ – i.e. anything which contradicts his government’s lies – about the Russian war effort.

Britain is a very long way from that kind of suppression of speech. If a publication wishes to condemn Boris Johnson for his handling of the Ukraine war, Covid or for anything else, its writers and editors will not be ‘disappeared’. But the stories themselves might be. A speech by David Davis questioning government plans for vaccine passports was taken down from YouTube – but online censorship is usually more subtle. Dissenting voices can be made harder to find online, or advertising removed from the videos.

The Spectator now encounters these censorship bots on a regular basis. If we publish academics who question the rigour of the science behind the government’s mask policy, Facebook can stick a ‘false information’ label on it – with no obligation to identify a single false fact. Lionel Shriver incurred the wrath of YouTube censors by reading a version of her column online. The Socialist Workers Party had its Facebook page removed entirely. Arguments that go against the grain are identified and then gently buried or wrongly labelled as fake news. This ought to appall the government. Instead, it wants to put itself in charge of the process.

Unlike the press barons, the tech giants do not care about free speech

At first, Silicon Valley’s pioneers put themselves forward as proud defenders of free speech: Twitter even described itself as ‘the free speech wing of the free speech party’. But now Twitter and other platforms have complicated censorship algorithms that either remove or downgrade (i.e., make it harder to find) stories that offend whatever orthodoxy is programmed into the system. When Twitter took down Donald Trump’s account (while allowing spokesmen for the Taliban to stay on the platform) it was a huge demonstration of raw power: a social media company could delete a sitting president from what has, in effect, become the public sphere.

The motives of Big Tech are not ideological but financial. They want to make money from adverts and avoid regulation – and will do whatever governments want to minimise the risk of that regulation. Their ability to tweak the news feeds of tens of millions of people gives them more power than Murdoch, Hearst or Beaverbrook ever wielded – but unlike the press barons, the tech giants do not care about free speech. They happily cut informal censorship deals with governments as long as they keep their power and ability to make money.

Such a deal is about to take place through the Online Safety Bill currently going through parliament. It is based on an acceptance that Silicon Valley now censors the news published digitally in Britain, but government wants the power to set the terms under which it does so. As is always the case with state censorship, this is justified by citing the worst filth imaginable: child abuse, revenge porn, glamorisation of suicide, promotion of terrorism. But it never takes long before the legislative scope widens to include things that ministers just don’t like. Nadine Dorries, who is overseeing the bill, has said that the more indelicate jokes of comedians like Jimmy Carr may fall on the wrong side of her line.

So the bill has presented social media companies with a choice: interpret the word ‘harmful’ liberally and risk being fined – or err on the side of caution and remove any content that might conceivably land them in trouble. We have already seen where this leads. During the pandemic, social media firms tried to guess what would and would not be seen as helpful by the government. At one stage, Facebook banned articles suggesting that Covid-19 might have originated in a Wuhan laboratory. It has since lifted this rule, but the episode shows the dynamic at play: what is removed is not so much what government bans, but what social media firms regard as risky.

Some will ask: why should we care about Facebook? And why should it not be trusted to moderate what is said on its platform? After all, no newspaper is compelled to publish content with which its editors dis-agree. But the problem is the sheer power and growth of digital media. A handful of private companies now control the way people find out information. More Britons get their news from Facebook than from any newspaper – but the daily ‘news’ feed is curated by the platform’s algorithm. Whoever controls these algorithms controls the news.

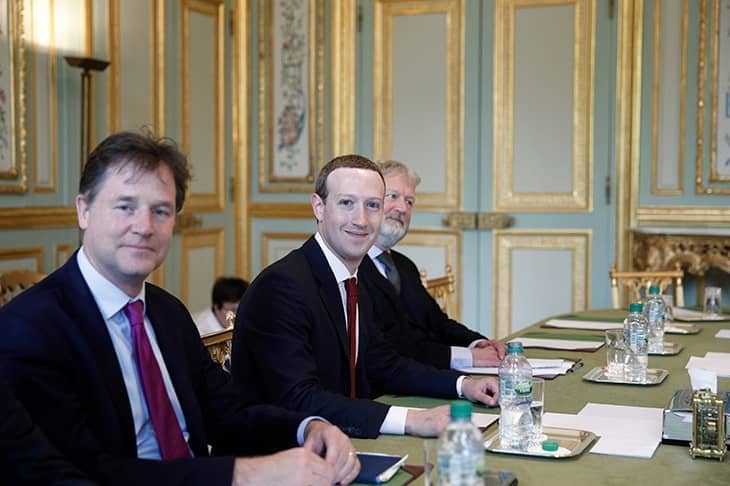

Social media sites claim not to be publishers, merely ‘platforms’ – a distinction which has, until now, allowed them to escape legal action for the libellous or other illegal content that they host. Such is their global reach that their ability to censor their users, and to do so silently, puts them in an incredibly powerful position. Nick Clegg, who now oversees policy at Facebook, has been promoted to a position of influence greater than any newspaper proprietor. The Online Safety Bill empowers Silicon Valley giants rather than calling them to heel. But politicians, who have worked on this Bill for years, do not understand the nature of censorship bots – or the effect of algorithms in deciding what news people do and don’t read.

It’s ironic that Boris Johnson, a former journalist and an erstwhile campaigner for free speech, is presiding over this legislation. Aides say that he is out of date and barely understands how anyone can get news from Facebook, let alone how that news is selected and censored. After office, he will soon find out how the censorship bots he’s about to empower will judge his own arguments. And how the power of Silicon Valley is already casting a shadow over the print press: all the more so when its bots are expected by the government to sure all articles are “safe”.

Ms Dorries says he bill will give special exemption to journalists. But why should freedom of speech and opinion not be available to all? Are we really to pass a law where the state decides who and who does not have the ability to say what they. please without fear of censure?

The BBC can often be guilty of a left-wing bias, but its power to influence national and international debate is tiny compared with the likes of Facebook, Google and Twitter. Why hasn’t the government realised that this bill will unshackle rather than restrain these companies? It needs to re-examine the proposed legislation and stop seeing online harm purely from the point of view of protecting children from damaging internet content. Ministers cannot sit by and allow Silicon Valley’s bots to stifle public debate.

Comments