Matthew Arnold cannot have been much fun on holiday. Watching waves crash on the pebbles at Dover Beach, he heard only metaphors for the decay of religion. The ‘Sea of Faith’ had once been full, but now its ‘melancholy, long, withdrawing roar’ filled his ears. Dominic Green thinks he was much too gloomy. He prefers Arnold’s chirpy contemporary Ralph Waldo Emerson, who perceived that faith was not so much ebbing as flowing into new channels.

From the time of the 1848 revolutions to the century’s close, railways, industrialised wars and questions raised by geologists and biologists shook people’s faith in Christianity. But the crisis of religion fuelled the expansion of religiosity. A motley crew of seekers understood their quest for modern kinds of meaning and selfhood as essentially spiritual.

Henry David Thoreau, groping after unity with nature by Walden Pond, became ‘America’s first yogi’

The forces knitting their westernising world together – from steamships to imperialism – encouraged cross-fertilising experimentation. They created not only networks of ideas, but the idea of the network, a word coined in 1839. In New England, Emerson learned to transcend divisions between Christianity and other faiths by reading Hindu texts in translations commissioned by Britain’s East India Company. While Arnold sorrowed by Dover Beach, Emerson’s disciple Henry David Thoreau groped after unity with nature by the calmer waters of Walden Pond, becoming ‘America’s first yogi’.

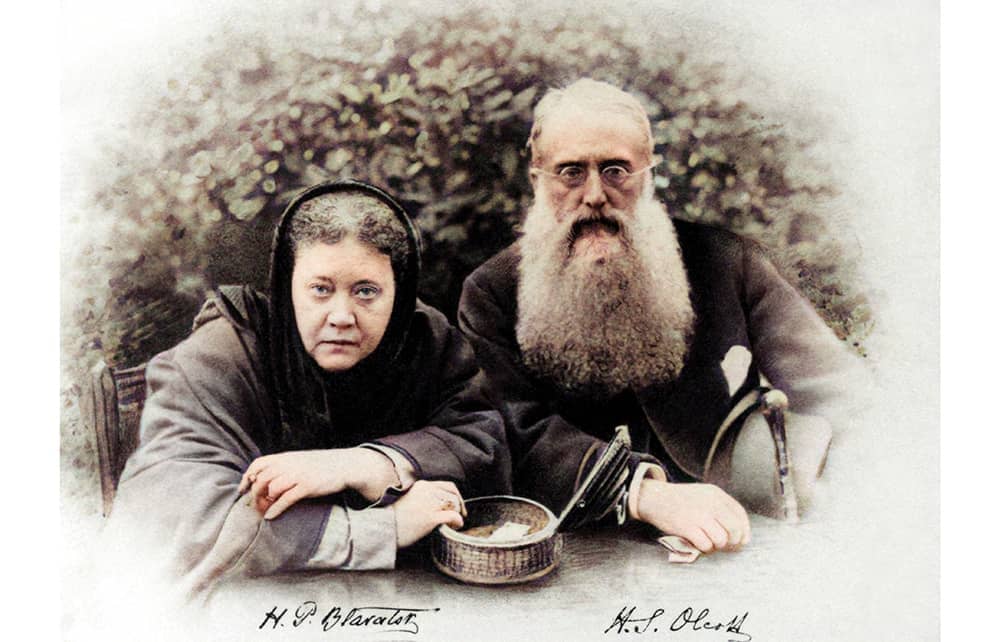

Green relies on demonstration rather than argument to make his case that religion’s loss was religiosity’s gain. He establishes his revolution by weaving together the biographies of the revolutionists who spiritualised modern technologies and ideologies. Some of them will be very familiar – Charles Darwin, John Ruskin, Karl Marx – and some obscure – the French occultist Éliphas Lévi, the American Buddhist Colonel Olcott.

His jump-cuts between his people’s complex, perplexed lives and world events – which read like a collaboration between Adam Curtis and A.N. Wilson – sometimes bewilder but also bring out unexpected parallels. It was not only the liberal Darwin who investigated human origins, but the Comte de Gobineau, whose defence of natural aristocracies went down well in the American South, where it justified a slave society. Walt Whitman’s experiences on the nursing wards of the Civil War encouraged him to publish joyous avowals of his love for male bodies, which became his ‘religion’. His contemporary Friedrich Nietzsche found it harder to accept homosexual urges. Closeted in Basel and frustrated in Bayreuth, where Wagner fretted over his excessive masturbation, it was only after a calming bout of sunbathing in Genoa that he was ready to rebel against Christian morals. His ideas were creative and explosive where Whitman’s were sunny and banal.

Nietzsche believed his insight into the hollowness of conventional morality could make him the ‘Buddha of Europe’. Green’s revolution is global, dragging the thought leaders of other faiths into dialogue with doubting Christians. He introduces us to Jamal al-Din al-Afghani, a roving Persian ideologue who urged Muslims to question the authority of their imams, but also to mount pan-Islamist revolts against European empires; to Vivekananda, who did yoga with Americans while recommending downtrodden Hindus to bulk up and eat beef; and to Theodor Herzl, the ‘Jewish Zarathrustra’, who dreamed of a German-speaking Zion in Palestine, complete with Viennese cafés.

The global market in faiths came to be dominated by Americans, who embraced the spiritual possibilities of social disruption with as much gusto as their descendants now exploit its economic opportunities. With ineffable chutzpah, Colonel Olcott sailed to Sri Lanka to bring about a Protestant Reformation of Buddhism. His collaborator, Helena Petrovna Blavatsky, might have been a chain-smoking Russian, but she was a quick study. The credulous people to whom she relayed spiritual messages from her invisible guru Koot Hoomi were disturbed by his ‘Yankee dialect’. The sales pitch for what Blavatsky and Olcott called Theosophy was American: it condensed all historic religions into a product which could be exported for consumption in any local market, much like Bovril, another contemporary invention. Many of Green’s revolutionaries, who went mad or died young before their teachings were accepted, would be horrified to learn that their fizzled revolutions led not to a New Age but merely to modern America, where ‘one in eight’ practises yoga and ‘one in five’ is ‘spiritual but not religious’.

Green’s rollicking book is grotesquely overwritten, but its mixed metaphors and excess facts are a fitting match for an age of cornucopia. The big problem with his concept of religiosity is that in enveloping every aspect of the later 19th-century world, it ultimately explains little. As he says of Blavatsky’s occultism, it simplifies without clarifying. It also leads him to omit the enormous majority of people who remained loyal to historic religions rather than to their beguiling substitutes. In this vital age of transition, revolutionised but enduring religions were no less important than ‘the religious revolution’.

Comments