Here are some statistics that ought to send a shudder through Tory MPs. Between 1995 and 2012 the French centre-right was in presidential power, first under Jacques Chirac and then the administration of Nicolas Sarkozy. The month after Sarko was elected president in 2007, his party, Union for a Popular Movement (UMP), won 313 seats in the National Assembly.

Today, following a rebrand to become Les Républicans in 2015, they have 62. This is actually better than some expected considering their 2022 presidential candidate, Valérie Pécresse, won just 4.8 per cent of the electorate’s votes, below the 5 per cent threshold required for candidates to be reimbursed their campaign expenses. Pécresse was reduced to publicly grovelling for funds to stave off personal financial ruin. It was the first time in the party’s history that their share of the vote had fallen under 19 per cent in the first round of a presidential election. Between 2017 and 2022 they shed an astonishing 5.6 million voters.

I’ve written previously in The Spectator about the wretched plight of the Socialist party, and its potential implications for the Labour party, which is seemingly hellbent on making the same mistakes as their Gallic comrades. But there are also similarities between the demise of the Republicans and the current state of the Conservatives.

Where did those 5.6 million Republican voters go between voting for François Fillon in 2017 and casting their ballot this year? Some didn’t vote. They were among the 26 per cent (12.8 million voters) who abstained from the first round of the presidential election and the 52.5 per cent who couldn’t be bothered to vote in last month’s parliamentary elections.

Much of what worries the Republicans’ electoral base also troubles that of the Tories

A sizeable number have switched their allegiance to Macron, in the belief that only he has the will and the drive to reform the country’s economy. Several of the party’s MPs have done the same – for example Édouard Philippe, who even campaigned for Macron’s party at the legislative elections in 2017 after becoming his first PM earlier the same year.

A minority voted for Marine Le Pen and her National Rally party, and a significant proportion backed Eric Zemmour, who polled 7 per cent in the first round of the presidential election. The callow Zemmour ran a terrible campaign, focusing almost exclusively on immigration and Islam, with barely a word to say about the economy, education or the terrible state of the health service.

Can the Republicans’ decline be arrested? For that to happen they desperately need a leader who appeals to grassroots supporters and, more importantly, who is capable of attracting new voters to the party, particularly the younger and less affluent.

That person certainly wasn’t Pécresse who, as I wrote last December when she was nominated the party’s presidential candidate, was ‘Macron in a blouse’.

In the nomination run-off, Pécresse beat Eric Ciotti, an MP in the city of Nice with more robust right-wing views. He has called for the army to be sent into the lawless inner cities and declared that if asked to vote between Macron and Zemmour he would plump for the latter.

Ideologically, Ciotti is close to Laurent Wauquiez, the leader of the Republicans from 2017 to 2019. With the backing of the grassroots, Wauquiez tried to move the party to the right during his short tenure. Ultimately he was forced out by Republican grandees, the most virulent of whom was Pécresse, who accused him of a ‘porosity’ with Le Pen’s party. The bad blood remains among these factions, and earlier this year Ciotti was described by one Republican centrist as ‘Wauquiez, but worse’.

When he was elected leader of the Republicans, Wauquiez dared to tackle issues that the party had been ducking for years. But when he spoke about Islamism and immigration it angered the centrists; it also provoked the ire of the mainstream media. In one television exchange, Wauquiez told his inquisitors: ‘In order to please you, you expect me not to talk about immigration. That would leave the monopoly of discourse on immigration to the National Front…for too many years the right has capitulated, it has given up on certain themes’.

Such rhetoric went down well with the grassroots but not with the majority of the party’s MPs. Many had been opposed to his nomination from the start, even starting a social media campaign during the leadership race, ‘TSW’ or ‘Tout sauf Wauquiez’ (Anyone but Wauquiez).

Two years of bitter infighting at a time when the party should have been working on a strategy to counter Macron resulted in a disastrous performance in the 2019 European elections, and Wauquiez quit as leader.

The centrists were triumphant. They were back in control. But they have now led the party to the edge of the cliff. Macron may be the man to give them the fatal push.

The signs are that, after his failure to win an absolute majority in the parliamentary elections, Macron is going to ally himself more with Le Pen’s National Rally than the left-wing Nupes. At the weekend the government announced a new immigration policy – the deportation of any foreigner convicted of a serious crime – which was welcomed by Le Pen, and one imagines, Laurent Wauquiez. With 89 MPs in the National Assembly, Le Pen’s National Rally has the opportunity in the next five years to become a credible political party, rather than the fringe far-right party commonly portrayed in the media. Such an outcome would be fatal to the Republicans.

The Tories would do well to reflect on the sorry state of the French centre-right in the coming weeks. Much of what worries the Republicans’ electoral base also troubles the Tories’: immigration, the culture wars and the economic implications of pursuing net zero. Boris Johnson won an 80-seat majority because voters assumed he would address these issues.

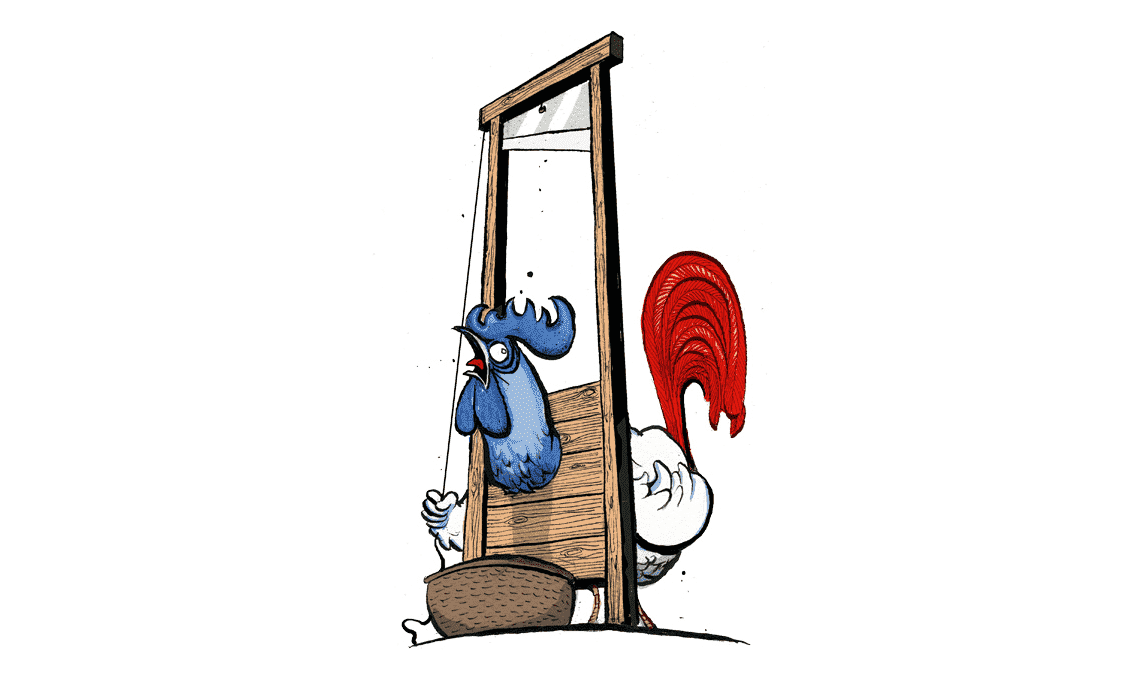

The next Conservative leader must have the courage to act or the party could go the same way as Les Républicains, particularly should Nigel Farage carry through with his threat to return to politics. Scoff at your peril. Who could have imagined as recently as 2017 that five years later Le Pen would have more MPs in the National Assembly than the party of Chirac and Sarkozy? Not a revolution to compare with previous French upheavals but a significant change to the country’s political landscapes.

Comments