The word ‘magisterial’ consistently attaches itself to the work of David Kynaston. His eye-wateringly exhaustive four-volume history of the Old Lady of Threadneedle Street established him as a historian with a confident command of a huge body of information, as bloodless and dry as the subject was. Embarking on Tales of a New Jerusalem, a history of Britain from 1945 to 1979, he has undertaken another marathon and earned magisterial rank.

Yet, from the first, Kynaston has shown that he is prepared to leave the bench to sweep the Ealing and Islington Local History Centres, Wandsworth Library, the East Riding Archives and especially that extraordinary resource, the Mass Observation Archive, kept in The Keep at the University of Sussex.

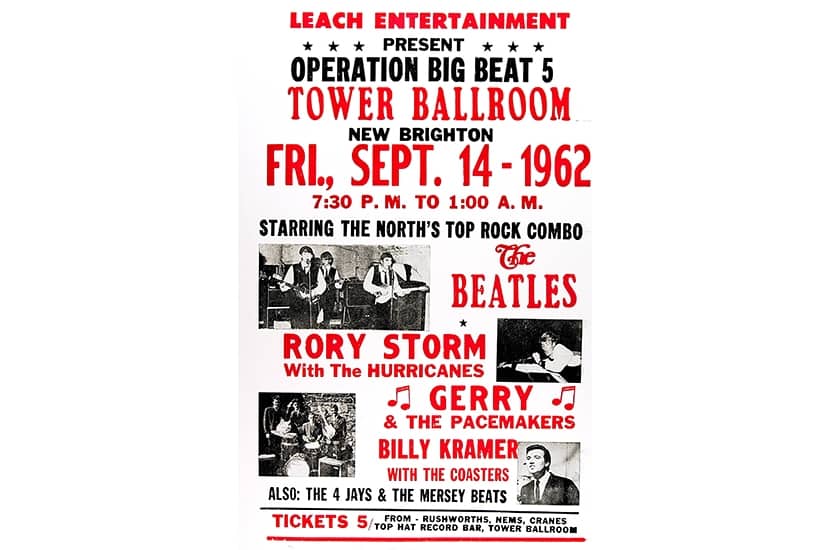

This is the fifth volume, just over half-way between the cabinets of Clement Attlee and Margaret Thatcher, but the significance is in the title, On the Cusp, from June to October 1962 —

a moment marked by the release of the first Beatles single and the premiere of the first James Bond film on the very same day. It is not intended as a comprehensive portrait of Britain at this time…

This is history not by excursion, nor indeed diversion, but by immersion in an extraordinary accumulation of detail. As with the first volume, Austerity Britain: A World to Build, 1945-48, this one is framed by observations from ‘ordinary people’. It opens, on the second Sunday in June 1962, with 17-year-old Veronica Lee with her father at church, St Swithun’s, Shobrooke, in Devon: ‘New parson, who looked like a sparrow & whistled.’

Next we turn to Rev. W.A. Wood from St James’s, Accrington, in Lancashire. In addressing the local motor-cycle club, he compares

motor-cycle scrambling to the ‘scramble of life’, which got everybody ‘out of breath’ from time to time; and just as the riders had to clean their machines, so people had to clean up their lives through reading the Bible and prayer.

And then ‘a few hours later’ the author takes us to the World Cup quarter-final against Brazil. Neither of the two television channels covered it; instead, the BBC’s Light Programme offered, at 9.45 p.m., a recording of the second half. England were knocked out 3-1.

More knock-outs were to follow on 13 July, with Harold Macmillan’s Night of the Long Knives, when the prime minister despatched a third of his cabinet. Jeremy Thorpe, riding high for another decade, pronounced: ‘Greater love hath no man than this, that he lay down his friends for his life.’ Sir David Eccles, sacked from Education, complained that he had been dismissed with less notice than a housemaid.

Ferdinand Mount is quoted (from 2008) as saying that these sackings marked a watershed in domestic policy. Before then, such actions may have had some weight. Afterwards, ‘they appear more like gestures of impotence… dictated by the last by-election or opinion poll’. Kynaston notes: ‘It is a plausible case. Good days to bury bad news were still a long way off, but politics was now on that cynical, damaging path.’

Another neat insight into Westminster was the Question Time performance of Margaret Thatcher, one of two joint parliamentary secretaries, who answered not only 14 of the 15 questions but also the supplementaries. Temporarily without a pensions minister, she promised one of her own backbenchers to pass on his message about the plight of pensioners ‘to my right honourable friend when I have one’.

As to the state of the nation, the sociologist Donald MacRae suggested that Britain was ‘the only country where calling someone clever is to abuse them’. Anthony Sampson’s pioneering Anatomy of Britain appeared soon after, with the thesis of the ‘country-going-to-the-dogs inadequacy in the modern world of Britain’s key institutions and their leaders’. The response of a dismissive Simon Raven was to hold out instead ‘for the virtues of complacency, nepotism, charm and the amateur spirit’.

The state of agriculture and rural Britain is a focus. Between 1951 and 1964 full-time workers on the land had fallen from 553,000 to 333,000. Many of the broad seasonal rhythms remained largely intact, and while old-time skills such as hand-milking, scything or thatching hay ricks were largely lost, new skills and multi-tasking fell to farmers.

A more recent study revealed that most villages in the year 2000 looked very similar to how they did in 1940, with their church, manor house, rectory or large farmhouse largely carefully conserved; yet their shops, schools and pubs were steadily closing. Inevitably, as that devoted Devonian chronicler E.W. Martin lamented: ‘The dry rot of depopulation has drained away some of the vigour and variety of social life.’ A north-west Essex farmer said in the early 1960s about Elmdon: ‘If you passed a man whose name you did not know and said, “Good morning, Mr Hammond”, you had a 50 per cent chance of being right.’ While Kynaston wryly notes:

In the same week [probably in August 1962] a butcher, a stranger from Ely with seven years’ residence, said bitterly: ‘Don’t ask me! You’d have to have been here since Hereward the Wake to belong.’

Meanwhile, immigration was beginning to change this homogeneity. Kynaston computes that residents of West Indian, Indian or Pakistani origin amounted to some 630,000, or 1.2 per cent of the total UK population, making a selective roll call of ‘their human range and the diverse talents they had brought with them’.

With their two channels, television was broadcasting classics such as Steptoe and Son and Morecambe and Wise, providing some escape from drudgery, but again this had its effect on social interaction. A British couple living in America, visiting old friends in and around Colne in Lancashire, cut short their holiday by a month because ‘whenever we suggested an evening out it seemed people were either about to watch Coronation Street or were too busy discussing it to do anything else’.

In November, That Was the Week That Was made its first appearance, fronted by David Frost, who would soon prove keen to join the establishment he mocked. Here Kynaston drills a little to identify the ‘type of public figures whom Frost and co. instinctively felt less than warm towards’. Among his examples are Betty Kenward, Lord Denning, Julian Amery, Hardy Amies and Hugh Trevor-Roper. Interestingly, he furnishes another list — the ‘alternative establishment’, figures less ‘easy prey for the satirists’, citing Noël Annan, A.J. Ayer and Asa Briggs; Lords Harewood and Weidenfeld; Stephen Spender and Roy Jenkins. He says that one should have expected the influence of the former to wane as the latter waxed; but no, ‘the birth of liberal England — if indeed it ever happened — would be long as well as strange’.

The second half of 1962 was an odd, unsettled time, made more so by what we know was to follow in 1963, thanks to Philip Larkin: the invention of sex. And so, with all that promise, the next volume is to bear the title Opportunity Britain.

On the Cusp has been accused of lacking a theme — of being a rather short, thin, tentative, twitching thread on the journey to New Jerusalem. But in fact Kynaston has barely dropped a stitch. This pandemic-inspired swatch builds upon the prevailing idea of modernity, enhancing the richness of a deftly woven tapestry.

Comments