Back in February, Olaf Scholz gave one of the most important speeches in his country’s post-Cold War history.

In it, the German Chancellor announced that the Russian invasion of Ukraine had produced a zeitenwende, or turning point, and that German policy must adapt. No longer could his nation live on the so-called peace dividend that the West has enjoyed for nearly three decades, and no longer could Germany be dependent on cheap Russian gas. Within three days of Vladimir Putin’s invasion Berlin had U-turned and promised to give Ukraine lethal aid, to spend a one-off $110 billion on the Bundeswehr (the German military), and to spend 2 per cent of GDP on defence. The failed policies of Scholz’s predecessors that brought Germany so close to Moscow were utterly rejected. The country had learned its lesson.

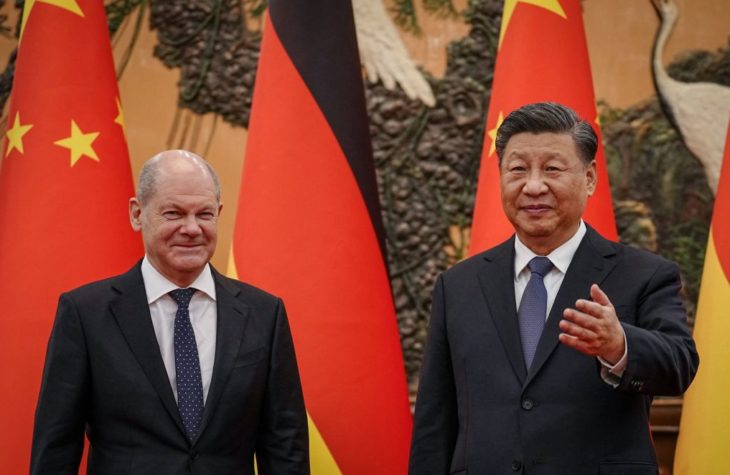

Or so it seemed. While Scholz has stuck to almost all the promises he made that day, German foreign policy towards the other major threat to world peace – China – has not fared so well. He met Chinese President Xi Jinping today; a trip that is not viewed fondly by Germany’s allies.

This is the classic modern European response: all words and no action

Yesterday, probably with an eye towards explaining why he was going to visit the communist leader, Scholz wrote a lengthy op-ed in Politico. In it, he recognised that the China of Xi’s third term is nothing like it was in his first, asserting that, in relation to the recently ended 20th Communist party Congress, ‘avowals of Marxism-Leninism now take up a much broader space’. He declared that Germany would reduce its dependencies on critical goods and materials from China, recognising that it does not want a repeat of Nord Stream. He also wrote that Berlin needs to be frank with China, willing to confront it on its extensive human rights abuses and today urged China to use its influence on Russia to press for an end to the war in Ukraine. He also said both Germany and China could agree on the fact that Russia’s nuclear threats are ‘both irresponsible and highly dangerous’.

While it’s good that Scholz wants to break certain dependencies on China, he is missing the most fundamental dependency of all: the broad reliance that the German economy has on China. As of last year the country was Germany’s largest trading partner, conducting over $246 billion in trade. Companies such as Volkswagen are also highly dependent on China, with sales to that country constituting more than double their second largest market: western Europe. Not surprisingly, the German Automobile Association is quite happy with Scholz’s visit. This kind of reliance on Chinese cash is as (if not more) potent as reliance on Russian gas. (The US is just as guilty, but at least in its case, China is equally dependent and Washington is actually willing to stand up to China and project power abroad in defence of freedom.)

What about human rights abuses? Even here, Scholz does not say anything revolutionary. He writes that Germany and China ‘will not avoid difficult issues in discussions with one another’. This is the classic modern European response: all words and no action. It is easy to have frank talks but it is hard to take concrete actions such as implementing sanctions. Germany has not even taken the simple and symbolic step of declaring the mass persecution of Uyghurs in Xinjiang to be a genocide, something many other countries have already done.

Now to the issue that has generated so much criticism: Chinese investment in the port of Hamburg. On 26 October, Scholz officially allowed the Chinese state-owned enterprise Cosco to buy a 25 per cent stake in the port. The move has rankled allies both foreign and domestic, and might have played a role in Scholz’s article yesterday. He claimed the ‘yardstick’ that Germany used was whether the investment ‘creates or exacerbates risky dependencies’ on China.

While a 25 per cent stake may not be a ‘dependency,’ it does give China another foothold in a critical European port and helps advance Beijing’s strategic interests. The fact is that China does not need another port investment – it is already heavily invested in ports all over Europe – it wants another port investment. More ports mean more influence and a greater ability to project power abroad. Approving the Hamburg port is yet another illustration of what results from a myopic conception of the Chinese threat.

Germany has made a lot of unexpected changes this year, so one can hold out hope that its China policy will be next. But if Scholz’s rhetoric is any indication, it doesn’t seem like a policy rethink is anywhere on the horizon. It is frustrating to watch as Germany is taught the same lesson over and over again.

This article first appeared in The Spectator’s world edition

Comments