Usually when the Commonwealth Fund releases its ‘Mirror, Mirror’ study of healthcare systems, it makes waves across the UK media. You might not recognise the formal title of the study, but you’ll be familiar with its findings: this outlier research tends to rank the UK National Health Service as one of the best healthcare systems in the developed world.

It’s a hallowed report for much of the UK medical community and commentariat, reaffirming their unquestioning devotion to the NHS as a truly unique system and the ‘envy of the world’. While other healthcare assessments – from the OECD, European Health Consumer Index, and World Health Organisation, to name a few – often set out the NHS’s shortcomings, the Commonwealth Fund study usually acts as a counterbalance. Uncomfortable truths about the health service can then be swept under the rug by those who are inclined to worship at the NHS’s altar.

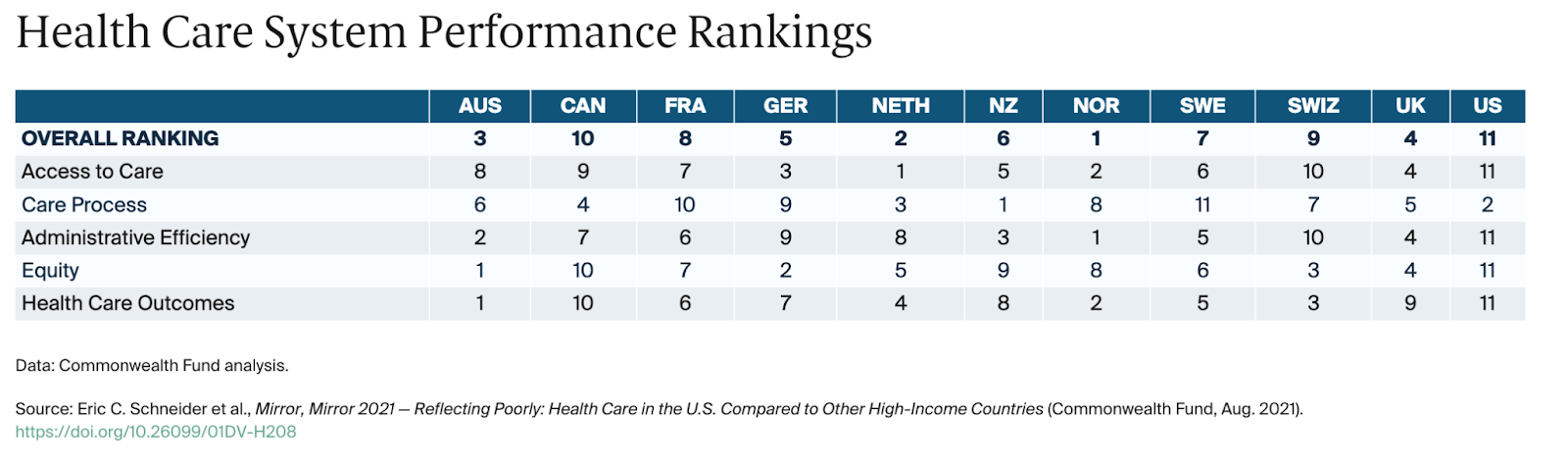

The report dropped last night, yet today’s response, compared to most years, has been much quieter. This is perhaps because the report’s findings suggest there may be new countries to envy: in the past four years since the last report was released, the NHS has dropped from ranking first overall to fourth, falling behind Norway, the Netherlands and Australia.

The system has been failing patients for far longer than the headlines suggest

Before we analyse the findings, it’s important to note how the research works. The Commonwealth Fund is fairly open about its preference for more centralised systems, like the NHS, which is why it uses ‘equity’ as one of its five major domains for assessing each system. Its goal is to reform healthcare Stateside, which explains why the major criticisms of the report are aimed at America – predominantly its high spending on healthcare, coupled with its unremarkable outcomes. It’s an argument that isn’t remotely controversial outside of the US, where every developed country offers some version of universal access to healthcare.

So why has the UK dropped down the rankings? The Commonwealth Fund think tank says it has fallen in key areas, including ‘access to care and equity.’ It’s a reminder that waiting times on the NHS were abysmal long before the pandemic hit, with the OECD noting in the mid-2010s that lack of efficiency in the NHS made it far more difficult for patients to access care.

There is no doubt that those frustrated with today’s findings will chalk up the NHS’s shortcomings as simply an issue of underfunding. But the fact that Australia ranks third in the Commonwealth Fund’s list, just above the NHS, makes this a tougher sell. Australia spends roughly the same percentage of its GDP (usually slightly less) on healthcare as the UK. According to the OECD, in 2019 the UK healthcare spending totalled 10.2 per cent of GDP, Australia 9.4 per cent. Yet on a similar budget, Australia’s hybrid system which mixes public funds and privately run services achieves much better healthcare outcomes, especially in life-or-death areas like cancer, and stroke and heart attack mortality rates.

The relative success of the Australian healthcare system is hard to contest, especially when the Commonwealth Fund finds similar problems with the NHS. One of the study’s five domains is ‘health care outcomes’ – how patients fare when they go through the system. In this the NHS ranks near the bottom of the pack, and has done even in years when it was ranked top overall. This year the NHS came ninth out of 11 countries in healthcare outcomes, in 2014 and 2017 it ranked tenth, only beating the US. Australia, on the other hand, ranks first. Switzerland comes in third, Sweden fifth: all systems that have struck the sweet spot of ensuring universal access to care, while using elements of the private sector to deliver faster, higher quality care.

When the NHS was ranked as the best healthcare system by the Commonwealth Fund in 2014, the Guardian wrote up a glowing review of the study, noting unironically that, ‘the only serious black mark against the NHS was its poor record on keeping people alive.’ This is perhaps the biggest lesson from today’s report too: the Commonwealth Fund’s findings today are not all that dissimilar to its findings in 2014 and 2017, when it ranked the NHS best in the world. The system has been failing patients for far longer than the headlines suggest and a refusal to acknowledge, or accept criticism, of the healthcare system’s failures has only made the situation worse.

How much longer will we refuse to confront these realities? They are growing more obvious and horrifying by the day, with Covid-19 exacerbating the many problems that saw the NHS almost reach breaking-point even before the pandemic struck. With the NHS waiting list in England now over 5 million, and the Health Secretary warning it could go as high as 13 million, the ability to turn a blind eye to this is growing harder by the day. Though one might argue that it was never justified to begin with.

Comments