I really loved Raymond Briggs. I first met him in 1976, before his mega-fame had arrived. I was working in the publicity department of Raymond’s publishers, Hamish Hamilton, and every so often he would trundle a wheelie suitcase into the office containing the painted boards of artwork for his latest cartoon story. His visits were a joy because he was so funny, but also tricky because unlike every other author under our promotional care, Raymond considered the less media attention he received to be the better.

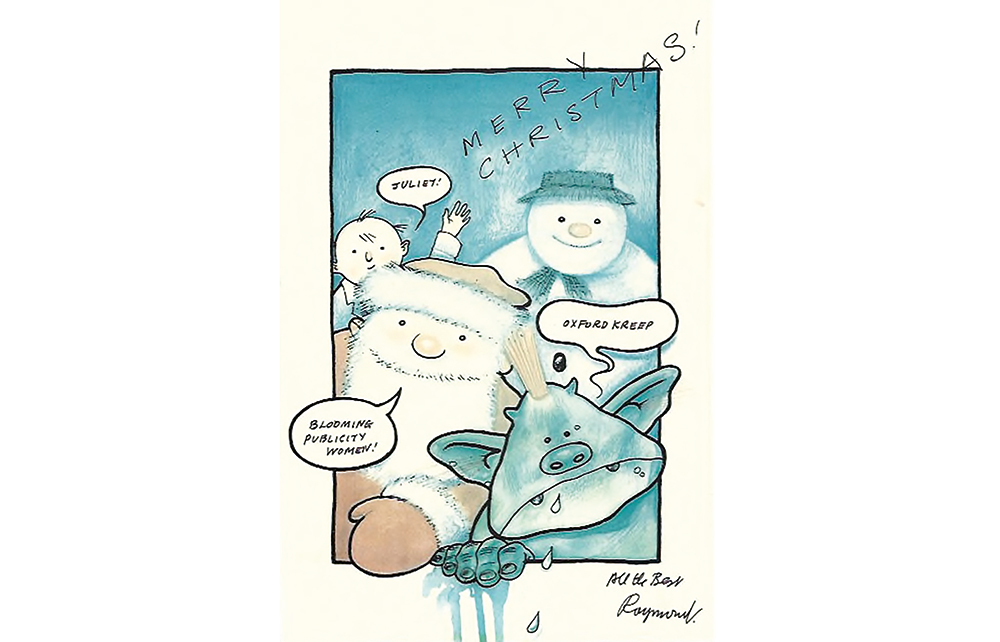

He referred to us as ‘blooming publicity women’ and we had to beg him to agree to talk to eager interviewers, and to submit to the scrutiny of TV and radio chat shows. The broadcaster Chris Evans, for example, was dismissed as ‘that ginger-haired git’. Launch parties were out of the question. Raymond was far more interested in talking to us than to the press. He struck up an excellent friendship with Brian the post-room manager, and they’d lock themselves in among the jiffy bags and proof copies and spend a good hour discussing their shared passion for the swing music of the wartime trombonist Glenn Miller.

We saw that it was loss and love as well as humour that provided the groundswell of his imagination

Raymond could never resist a tease. For some long-forgotten reason he positioned me as the object of an unrequited love-crush by the comedian Barry Took. No conversation was complete without a reference to Barry Took. ‘Seen anything of that old rascal Barry Took recently?’ he would ask. ‘Let me know if Barry Took is giving you any bother.’ The fact that I had never met Barry Took was irrelevant. One Christmas an envelope arrived addressed to me in his distinctive script. The card inside read: ‘Got a craze for Spoonerisms now, so my new name for you is JULIET SICKLE NUN. Violent but religious? Hope you like it.’

Everyone in the office knew that beneath the harrumphs Raymond was grieving first for his parents who had both died in 1971, and also for his beloved wife Jean, who had died two years later. We saw that it was loss and love as well as humour that provided the groundswell of his imagination and his character. Father Christmas, a grump-bag fed up with the onerous and repetitive tedium of the Big Night, is inspired by Raymond’s milkman father. The much later Ethel and Ernest (1998) covered his parents’ courtship, Raymond’s own birth and upbringing, their long happy marriage and their eventual parting in death. One of the graphically shocking frames depicting his mother on her death bed shows a clock stopped at 3.17: a time of day Raymond would never forget. More an adult post-war social history than a children’s book, this was perhaps the work of which Raymond was quietly proudest.

After Fungus the Bogeyman (1977), I remember some puzzlement when we heard there would be no text in his next book. Then we saw the ethereal pictures of a magical snowman and his friendship with a young boy – a ringer for Raymond as a child. His editor, Julia MacRae, wept when she saw it.

After The Snowman, Raymond produced yet another curmudgeon, a dissatisfied lavatory cleaner called Gentleman Jim (1980), followed by two fearlessly politically angry books. In When the Wind Blows (1982) he slaps down the reality of nihilistic nuclear terror on to a scorched but otherwise empty double-page spread. The Tin Pot Foreign General and the Old Iron Woman (1984) is a satirical attack on the Falklands War and the then prime minister Margaret Thatcher. One never knew what the trundling suitcase would contain next.

Later I lived near Raymond in Sussex. It was a county he often incorporated into his drawings: the Brighton Pavilion and the sweeping undulating Downland were part of the magical landscape over which snowman and boy flew hand in hand. We would meet in a café in the local town for a bun, a cuppa and a mutual grouse about the state of the world, the trouble with neighbours and the unmanageability of life in general. At his insistence we would take a table at the back, tucked well away out of fan-sight. Only after huge objections were overruled did he once finally agree to go with me into the local Waterstones a couple of days before Christmas, where the staff were gobsmacked to find their Christmas bestselling author reluctantly agreeing to sign their stock in his beautiful handwriting.

No Christmas mantelpiece in our house has ever been complete without Raymond’s advent calendar showing Santa wishing us a ‘happy blooming Christmas’. Our Christmas card from him never contained anything remotely festive. Instead we would receive therapeutic advice for counteracting the pall of gloom engulfing 25 December or a newspaper clipping about rising funeral costs captioned – in Raymond’s writing – ‘better hurry up then’. Old age and death became his inspiration. When he was awarded the Book Trust Lifetime Achievement Award in 2017, I rang up. Muttering that it had come ‘better late than never’ he refused to discuss the subject further, but I could hear him smiling.

Since Raymond’s death in August all the greats, including the children’s laureates Cressida Cowell, Julia Donaldson, his former art student Chris Riddell and Michael Rosen, as well as Helen Oxenbury and Posy Simmonds, and Briggs fans across the world, have come to praise him. This December multiple generations of children, parents, even grandparents will prop their F.C. (Raymond version) advent calendars on their mantelpieces. But in our home the treasured funeral card that is usually brought out for display will stay in the drawer. It’s not so funny this year.

Juliet Nicolson’s Frostquake: the Story of the Frozen British Winter of 1962-3 is out now.

Comments