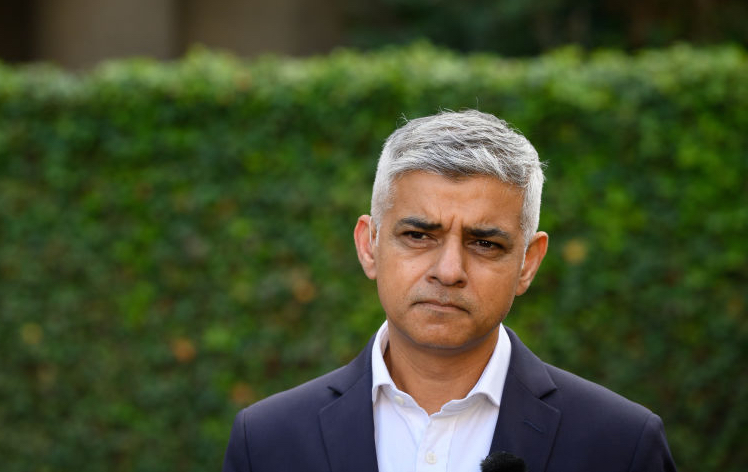

Sadiq Khan has an inveterate desire to show Londoners who is boss: the mayor’s latest wheeze is an expansion of London’s Ultra Low Emission Zone (Ulez). Khan is seeking to roll out Ulez to all of London’s boroughs from August – along the leafy lanes of Surrey, Kent, Essex and Hertfordshire.

Aside from ostentatious green zealotry, it’s difficult to see any convincing argument in favour of doing so. These areas already have sparser public transport than the rest of London. Charging hard-pressed residents who are unable to afford a fancy car £12.50 a day for the privilege of driving to the station to catch a sustainable train is a slap in the face. It could also backfire by encouraging them to do the whole run by car. Knocking that daily charge from the profits of carriers making home deliveries will also impoverish both them and residents hit with higher prices.

An argument that Khan is acting illegally is apt to fall flat

A number of outer boroughs – some, but not all, Tory – have vowed to fight the plan. The boroughs of Bexley, Bromley, Hillingdon and Harrow are considering clubbing together to launch a legal challenge. This backlash is understandable. But these boroughs should pause a moment and think again. Even if expanding the Ulez scheme is a mistake taking the fight to the courts is a bad idea.

Why? Because any legal challenge faces an uphill battle to succeed: going against social policy and environmental decisions of this sort in court is not easy. True, a challenge could triumph (decisions on judicial review are often unpredictable), but it will probably fail; and even if it succeeds it may well be possible to bring the scheme back with the legal glitches removed.

If it fails, the costs are likely to be big. Taxpayers in the outer boroughs, already hit by high house prices, high costs of living and painful commuter fares, will not thank their elected representatives for spending large amounts on a quixotic but probably bootless exercise. In a similar case to Scotland and Alister Jack’s veto of its gender legislation, Nicola Sturgeon has already given a big hostage to electoral fortune. The First Minister has seriously harmed the SNP’s popularity; saying she wants to blow Scots money on litigation she has been told many times she will probably lose is hardly a vote winning strategy. Tory councillors in outer London, who need all the electoral goodwill they can muster – and desperately need to promote the Conservative party as a decent steward of public funds – should take note of Sturgeon’s error. There is little to be gained from making a political point in court at someone else’s (in this case, the taxpayers’) expense.

But Conservatives should also be wary for another reason: the Ulez debate is a matter of politics. Calling for the courts to make a final decision is a move that could ultimately backfire.

There is a time and a place for judicial review: if Transport for London (TfL) was contravening some fairly explicit prohibition in the legislation allowing Ulez’s, for instance, then going to the courts would be entirely appropriate. Public bodies should act lawfully. But, as Richard Ekins and others have pointed out, there are limits to this principle. When it comes to judicial review based on more nebulous concepts – such as whether Khan is right, and indeed has the power, to expand this scheme – it pays to be cautious.

While we don’t yet know what the basis of any review of Sadiq Khan’s decision will be, it is quite likely to amount to something fairly vague, such as acting disproportionately or omitting to take into consideration some factor or another which the courts will be asked to see as relevant.

Yet there is a strong argument that, even if the extension of the Ulez is a terrible idea, this is precisely the kind of case that should be left to political determination by elected bodies, whether you agree with them or not. After all, this is what democracy, and perhaps more importantly judicial independence from politics, is all about. Those who do not like the decisions reached should fight on the political, not the juridical, plane. There are at least three reasons for a Conservative government to embrace this position loudly and unequivocally.

One is a long-term argument. If, as seems likely, the party finds itself in opposition from next year, it should lay the groundwork for giving maximum scope to future Tory local authorities to decide what they see best for their residents without an ever-present threat of judicial review.

Secondly, taking this position makes it much easier to wrong-foot Sadiq Khan. The Tories desperately need to find a way to focus opposition to his excesses and make political capital – something currently in short supply – out of them. An argument that Khan is acting illegally is apt to fall flat, get bogged down in technicality, and remind people of leftists’ dreary harping on about their theory of the rule of law. By contrast, a bold statement by the government that it absolutely supports democratic decision-making at the local level gives it great scope for then tearing into Khan. It can make hay from pointing out that Khan’s decisions on TfL and other matters are terrible – and call on Londoners to do the obvious thing and vote Labour out of office next time round.

The Tories could, if they wanted, take the battle even further into enemy territory. A commitment to change the law to allow each London borough to decide for itself on environmental matters such as the Ulez – and hence in future decline to accept extension of the Ulez on an impeccable legal footing – would be attractive to voters fed up with the antics of those in City Hall. It would also give the Tories the opportunity to confirm their position as the party of genuine local decision-making (incidentally stealing at least some clothes from the Liberal Democrats in the process). Now, that would be an eye-catching start to the campaign for the next elections, both local and national.

Comments