On the road to the frontline Andrii, 36, managed to coax the tired old British ambulance up to 80mph.

The tarmac ahead was scarred with the impact of artillery shells and some of the holes were big enough to pitch us off the road, but he navigated around them skillfully.

Suddenly, far in front of us and high above, we saw the contrails of an airplane: an innocuous sight in a peaceful country. Here it almost certainly meant an incoming Russian strike. Andrii and his helper, Oleksandr, 29, donned their body armour.

And then from our left a new contrail appeared: a Ukrainian missile. The first contrail made a sudden and tight 180 degree turn, revealing that it was a Russian fighter jet. The pilot must have suddenly become aware of the incoming missile.

For a while it seemed like the Russian would get away. But the missile was moving faster than the plane and, as we watched, it closed in. Then the contrails merged. The two thin white lines turned into a thicker, billowing trail. Then there was nothing except blue winter sky.

I was travelling with a Canadian colleague and we watched mesmerised. But the Ukrainians we were travelling with barely battered an eyelid. ‘There’s always something going on on this road,’ Andrii said.

For an outsider the run to Orikhiv, a small town on the frontline an hour east of the Ukrainian city of Zaporizhzhia, is an eye-opener. The last ten miles of the road are deserted except for military traffic. In the background there is the constant thud of incoming artillery shells, and sometimes the distinctive sound of a multiple rocket launcher releasing its load.

At the entry to the town itself we were greeted by two unsmiling soldiers at a checkpoint, several shops with their roofs blown off, a burned-out car, chunks of debris and strands of dangling wire. But for Andrii and Oleksandr this is their daily commute.

War, like so much news, is often presented in dramatic highlights: a tank firing, a civilian running, western aid workers feeding begging, starving people. But the reality is more prosaic, even humdrum.

‘I do this run Monday to Friday every week,’ Andrii said. ‘I’ve been doing it for months.’ Andrii is one of a network of many thousands of local volunteers that keep supplies running to Ukrainians still living by the frontline. Each day the volunteers head out on battered roads, sometimes under fire, in vehicles that would never pass a safety test in the West.

The previous day, while interviewing officials in Zaporizhzhia, we had been told about an aid convoy into Orikhiv. The town was of interest as it had been the scene of fierce fighting a few days before.

Before the war Orikhiv and the surrounding villages had 13,000 residents. Now four of its satellite villages are occupied by the Russians. But as many as 1,800 residents still live in the area under Ukrainian government control.

I naively imagined we would be travelling with a lorry laden with food and medical supplies. As it turned out, our transport was the battered English ambulance. My seatbelt didn’t work and I sat in the front middle seat, my protective helmet banging against the roof.

In the back was our cargo: a few dozen wooden planks (residents had asked for them to fix their damaged roofs). There was also an ancient wheelchair destined for an 83-year-old.

Eleven months into the war, Orikhiv, like many frontline towns in Ukraine, has settled into an uneasy if not entirely predictable rhythm. During the morning the shelling is usually light. It often picks up in the afternoon, and then intensifies overnight.

So we aimed for an early departure. Our destination in the town was to be the ‘point of resilience’ – a sort of municipal centre that the Ukrainian government has mandated should be set up in every community in the country.

Supplied with a generator and a wood stove, and sometimes a satellite internet connection, these centres (the one in Orikhiv was only a few tiny rooms with a dozen chairs) offer residents hot drinks, power and warmth.

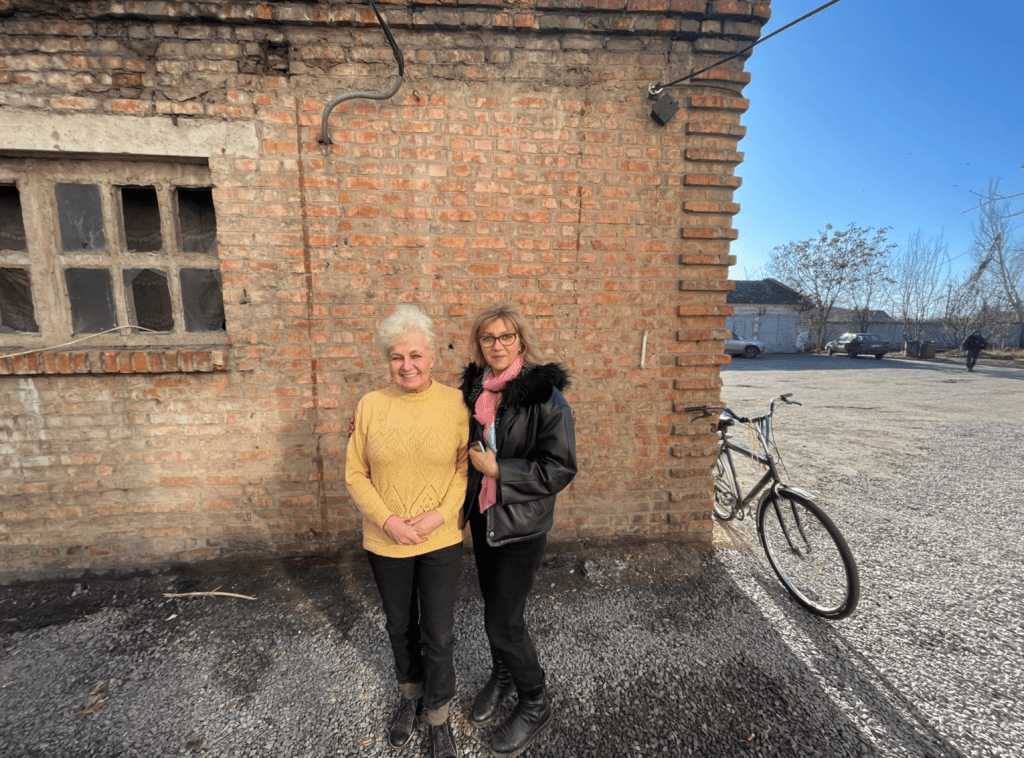

When we arrived at the centre we were greeted warmly by two local women. Lyubov was the 59-year-old head of the centre. Svetlana, 39, who had worked in a pastry shop before the war, was helping her. They brought us hot coffee.

Svetlana said she had decided to stay in the town because her parents, both in their eighties, were still living in an outlying village, only a couple of miles from the Russian positions. ‘Twice a week I take them wood and bread,’ she said.

Lyubov said they were among many elderly locals who were simply unwilling to leave, despite the risks. ‘Even if they get no help at all they will not leave,’ she said. ‘They will eat vegetables from their gardens, even starve, but they won’t go.’

Others had stayed to look after pets. One lady said she had taken in 16 stray cats and dogs.

Lyubov lives about half a mile from the centre in a block of flats that once housed a hundred residents. Now there are only three left. Six months ago, fed up with patching up her broken windows and the noise of the shelling that kept her awake at night, Lyubov cleaned out the debris in the unused basement of the large Soivet-era building. ‘I needed to sleep,’ she said. ‘And it was simply too noisy in my flat.’

She gave us a tour of her underground home by torchlight. Outside news was beginning to filter through of a fresh wave of Russian missile strikes that killed 11 civilians in different parts of Ukraine.

In Lyubov’s basement cuddly toys, cosmetics, lotions and perfume had been carefully arranged in front of a mirror. There was a fruit bowl with bananas and apples. Lyubov had placed hangings on the wall to cover the bare concrete.

‘I go to the city once a month,’ she said. ‘I go to attend a city council meeting – and get my nails done.’

Her husband, who was the local chief of police, had died ten years ago of cancer. Her son is married and lives in Kharkiv, Ukraine’s second city. She hasn’t seen him for 18 months. Her only companion is a cat called Tana.

Nevertheless she had two beds carefully made up. ‘One of them is in case I ever have a guest,’ she said proudly.

Julius Strauss runs the newsletter Back to the Front about Russia, Ukraine, Afghanistan and the Balkans.

Comments