In a newspaper article five years ago, Michael Gove singled out the tax exemptions enjoyed by private schools thanks to their charitable status as one of the ‘burning injustices’ of our time. He took it for granted that scrapping these benefits would raise money and proposed spending it on children in care instead. ‘How can this be justified?’ he said of the exemptions. ‘I ask the question in genuine, honest inquiry.’

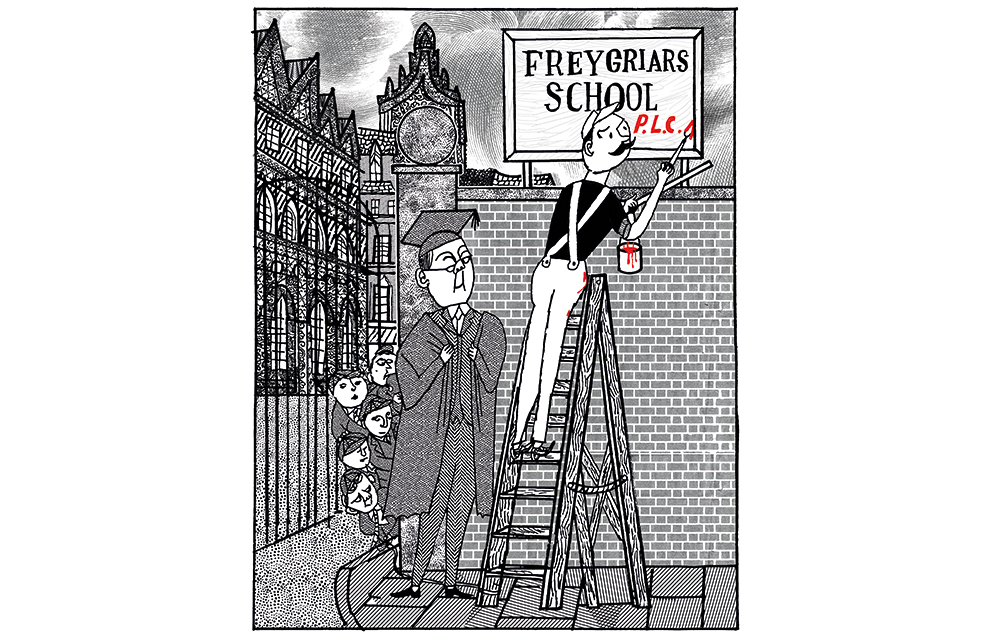

Answer came there none, and Keir Starmer has now said that private schools will be treated like any other commercial business if Labour wins the next election. Since that looks quite likely, I thought I’d take up Michael’s challenge and say why I think that’s a bad idea. The ‘genuine, honest’ answer is that ending private schools’ tax benefits will lose the Treasury money, harm social mobility and won’t make our education system any fairer.

It will mean fewer bursary places and less partnership work with state schools – not to be sniffed at

Starmer claims adding VAT to private school fees will raise £1.6 billion a year, while making the schools fully liable for business rates will raise another £104 million, and he has pledged to spend this bounty on a ‘catch-up’ programme for children who fell behind during the pandemic. A worthy cause, to be sure, but the Labour leader will have to find the money from somewhere else because his sums don’t add up.

To arrive at the £1.6 billion figure, Starmer has assumed the total amount parents spend on private school fees in England and Wales won’t change as a result of this policy and multiplied the current total by 20 per cent. But according to an analysis by Baines Cutler, a consultancy that provides financial advice to the independent schools sector, that’s way off the mark.

To begin with, if private schools become liable for VAT they will be able to claim it back on supplies, such as building materials and transport, which means their costs will fall and they can afford to drop their fees a little before adding VAT. Baines Cutler estimates that the tax take from adding VAT will be more like 15 per cent of what parents are paying now, not 20 per cent.

But a 15 per cent rise in fees will still make private education unaffordable for many parents, which will mean some schools close while others attract fewer pupils. An overall reduction of 25 per cent is ‘reasonably likely’, according to Baines Cutler, which translates to about 135,000 children.

To the opponents of independent schools, that will sound implausible. According to Gove, private school parents are among ‘the very wealthiest in the world’, and therefore able to soak up big hikes in fees. But that’s not so, according to David Woodgate, the chief executive of the Independent Schools’ Bursars Association. ‘In a lot of families, all of the second income goes on school fees,’ he says. ‘It’s wrong of Labour to categorise our parents as being price-insensitive.’

So the loss of 135,000 pupils isn’t too much of a stretch, particularly when you factor in that the 15 per cent rise in fees will come in the midst of a cost-of-living crisis. Not only will that reduce the VAT bonanza (we’re now down to just over half of Labour’s predicted £1.6 billion),it also means the Department for Education will have to educate these children in the state sector. If you add the capital cost of building new schools to accommodate an additional 135,000 students, Baines Cutler estimates the policy will actually cost the taxpayer £416 million a year after five years.

Perhaps that’s unduly pessimistic. Baines Cutler was commissioned by the Independent Schools Council (ISC) to produce this analysis, so it should be taken with a pinch of salt. But the policy will, at best, be cost-neutral. So you can forget about having more money to spend on children in care or extra lessons for those who have fallen behind.

Why will it have a negative effect on social mobility? Partly because, having been denuded of the tax benefits of being charities, independent schools will no longer have a financial incentive to maintain their good standing with the Charity Commission. That will mean fewer bursary places and less partnership work with neighbouring state schools, which is nothing to be sniffed at. At present, about 85 per cent of independent schools have formed partnerships and at least 40,000 pupils benefit from means–tested scholarships and bursaries.

Barnaby Lenon, chairman of the ISC, told me that many former direct grant schools, such as Reigate Grammar, the alma mater of Starmer, are trying to return to a policy of admitting the most able applicants, regardless of ability to pay. Before the direct grant status of these schools was ended in 1976, the local authority paid the fees of pupils from low-income families; today, wealthy alumni pay for the lion’s share of the bursaries. Manchester Grammar, for instance, currently funds around 200 bursary places, with most covering 90 per cent of the fees.

No doubt independent schools will continue to offer some places to children who can’t afford the fees, but the direction of travel within the sector, which is to offer more and more bursaries, will be reversed. That will mean fewer Keir Starmers, whose mother was a nurse and father a factory worker, benefiting from a private education.

The bigger concern is the impact all those private school refugees will have on the state sector. The places they take up will inevitably be in the highest-performing state schools, squeezing out children from disadvantaged backgrounds.

We all know parents who have become masters of gaming the state system, whether it’s by masquerading as pious Christians or moving into the catchment areas of outstanding academies. That’s partly why the schools with the best exam results have a below-average number of students on free school meals. Unfortunately, that number will fall even further once this ‘squeeze the rich’ policy has been implemented.

I’ve encountered this problem directly at the school I helped to open in 2011, the first free school to sign a funding agreement with Michael Gove when he was education secretary. To make it harder for middle-class parents to monopolise the places, we decided to allocate half of them by lottery. But as the school has done well – it was ranked in the top 5 per cent of state secondaries in the Times’s latest good schools guide – aspirational parents have inevitably beaten a path to its door.

The governors have tried to address this by reserving a quarter of the places for children eligible for the pupil premium, but it’s a constant battle and one that will undoubtedly get tougher if some local middle-class families can no longer afford school fees. Incidentally, the vast majority of high–performing state schools don’t prioritise applicants from disadvantaged backgrounds, which will make life easier for all those private–school émigrés seeking a soft landing.

There are other difficulties with the policy pointed out by Barnaby Lenon and David Woodgate. At present, all educational charities in England and Wales enjoy the same tax benefits – there’s no VAT on university tuition fees, for instance. Presumably, Starmer will want to target only private schools, but that’s easier said than done. Is he aware that the majority of special-needs schools are independent, albeit with the fees usually paid by local authorities? And what about all the private music and dance schools, such as the Royal Ballet, which produce almost all the country’s top performers?

No doubt the legislation can be drafted in such a way that it singles out one subset of private schools for fiscal punishment, but then we run into another difficulty, which is state overreach. Do we really want the government to decide which charities are eligible for tax exemptions on purely political grounds? Once this Rubicon has been crossed, what’s to stop a Labour administration removing charitable benefits from right-of-centre thinktanks like the Institute of Economic Affairs, the Adam Smith Institute and the TaxPayers’ Alliance? Isn’t our society polarised enough without the tax status of charities being mucked about with to score party political points?

The attack on private schools rests on the assumption that they confer an unfair advantage on their students, tilting what should be a level playing field in favour of the better-off. But is that true? Five years ago, I was a co-author of a paper published in a peer-reviewed scientific journal that, among other things, looked at whether children at private schools did better in their GCSEs than children at state schools once you control for all the characteristics they arrive at school with – prior attainment, parental socio-economic status, genetic markers associated with educational success, etc. Surprisingly, we found that going to a private school made very little difference.

We all know parents who have become masters of gaming the state system

The conclusion I came to is that private schools aren’t a great investment, at least as far as GCSE results are concerned. More importantly, they aren’t the drivers of educational inequality that critics like Gove think they are. In light of this, it seems completely irrational to penalise them by removing their tax benefits. If some parents want to pay through the nose to send their children to these establishments, thereby relieving the state of the burden of educating them, we should be grateful, not resentful. Those parents are paying for education twice over – once for their own children and once for other people’s. Shouldn’t we just say ‘thank you’ and leave them alone?

In short, Starmer’s private schools policy is just another piece of pointless virtue-signalling. It will almost certainly cost the taxpayer money, it is more likely to damage social mobility than improve it, and it won’t make our education system any fairer. I expect it will be implemented in full.

Comments