In the beginning, there were two nations. One was a vast, mighty and magnificent empire, brilliantly organised and culturally unified, which dominated a massive swathe of the Earth. The other was an undeveloped, semi-feudal realm, riven by religious factionalism and barely able to feed its illiterate, diseased and stinking masses. The first nation was India. The second was England.

So began Alex von Tunzelmann’s 2007 end-of-empire classic, Indian Summer. Now Courting India by Nandini Das traces the first encounter between these vastly different worlds, offering a fascinating glimpse of the origins of the British Empire.

The world into which we are dropped is in many ways eerily familiar. Jacobean England has only just recovered from a devastating plague, and its rift with Europe over the Reformation has led to a disastrous economic fallout. England is anxious about her place in the world and desperate for new trading partners.

At one point Roe wonders whether it might not be more profitable for England just to resort to piracy

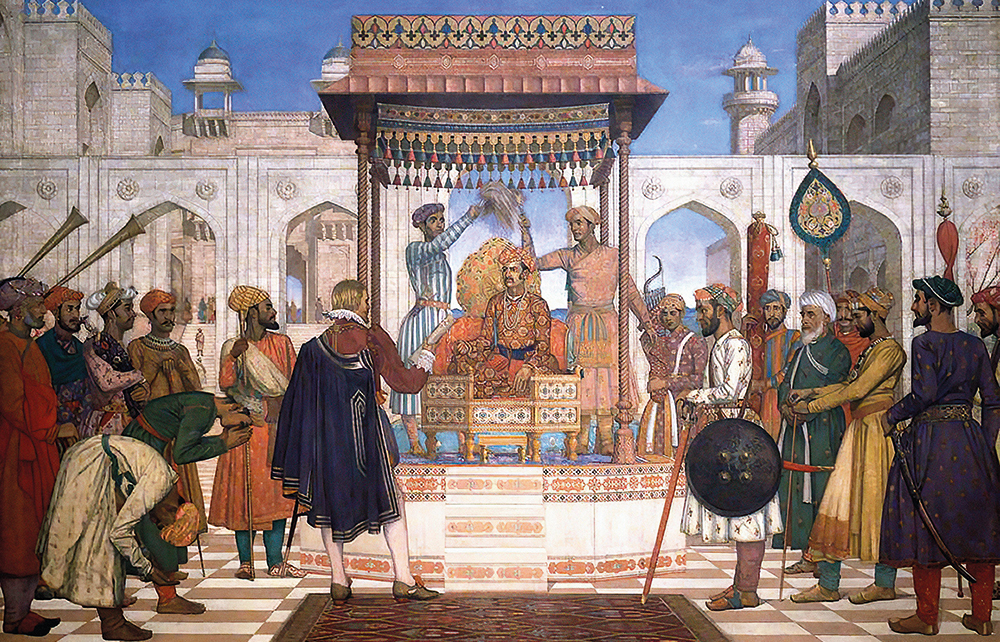

At the story’s centre is Sir Thomas Roe, a dry, prickly man from Essex, who ‘wears his sense of English superiority like armour’. Nicknamed ‘Honest Tom’, he is well-travelled, and, having failed to track down El Dorado in the Amazon basin, is appointed the first ambassador to Mughal India, ‘widely considered to be one of the greatest and richest empires of the world’. The book is slow to start, but once Roe’s ship finally arrives, in September 1615, at the Indian port of Surat, a ‘city of great fame and antiquity’, we enter an exciting world.

Later generations would characterise Roe’s visit as part of a golden age of exploration, when enterprising England suddenly threw open the gates of global trade. But his four-year mission was in fact largely a failure. The Mughal court showed little interest in trading with a small island in the North Sea. East India Company officials tended to be ignored, since there was little of value they could offer the fabulously wealthy emperor Jahangir.

Roe wasn’t greeted with the fanfare he expected, and his first experience of India was a frustrating parlay with bureaucratic customs officials. His cook got drunk on Armenian wine and started a fight with a passer-by, who turned out to be the governor’s brother. The cook was sent to prison, and the Mughals forbade other merchants to trade with the English embassy. Later, the governor had one of Roe’s men whipped for trying to sneak his goods out of customs, where they were still stuck. The English, it seems, had not made a favourable impression. It was only several months later that a farman from Jahangir finally acknowledged Roe as a visiting ambassador and invited him to the court at Ajmer.

Through Roe we get an intimate view of courtly Mughal life, from feasts with governors to wine-soaked evenings with the emperor himself. At one point Jahangir tries to persuade his more orthodox Muslim son Khurram to share wine with him, as he regards drinking as a useful social skill for an emperor. Khurram would one day build the Taj Mahal.

Even more fascinating than how the Mughals perceived the English is Roe himself. In many ways he is remarkably similar to the generations who would follow him to India. He refuses to learn Indian languages, and has to rely on a Protestant Italian jeweller as his interpreter, with whom he can only communicate in broken Spanish. In a revealing moment, he wonders in his diary whether it might not be more profitable for England just to resort to piracy. Yet his inner conviction that ‘peaceful trade rather than settlement should define English policy in India’ belies stereotypes. Roe is on the back foot until things gradually begin to turn in his favour after he makes a fateful wager with Jahangir. Gradually making his way into the emperor’s inner circle, he carves out the foundations of Britain’s empire in Asia.

The picture that emerges of the first official encounter between Jacobean England and Mughal India is a vivid one, drawn in dazzling technicolour. Courting India is as much about Britain as India, a glimpse of one of history’s turning points, and the start of a relationship that would change not just England but the world.

Comments