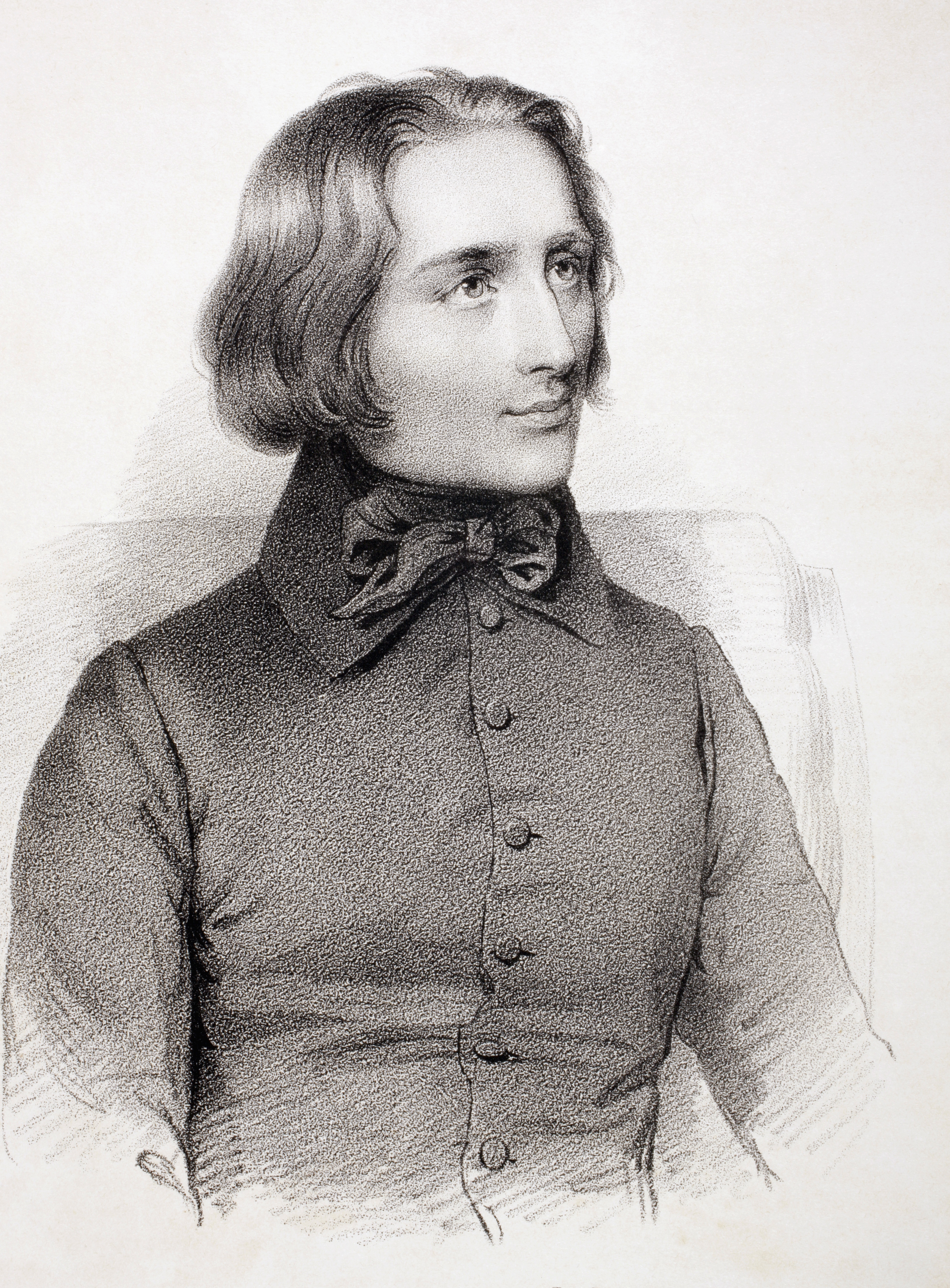

In 1875, Franz Liszt told a pupil of the kiss of consecration – the Weihekuss – that Beethoven bestowed upon him more than fifty years earlier. After watching the young Hungarian prodigy play works by Ries, Bach and Beethoven himself, he kissed Liszt on the forehead and said: ‘Go! You are one of the fortunate ones! For you will give joy and happiness to many other people.’

Liszt isn’t giving joy to many people these days. Take this year’s BBC Proms, which feature only one piece by Liszt, compared to two by Aaron Copland, four by Dora Pejacevic, and six by Samuel Taylor-Coleridge. Over the past decade, Liszt has appeared in eight Proms, while Rachmaninov has featured in 40. The works featured, too, have done him few favours: the two piano concerti, which are not among his greatest works, account for a third of his scanty presence.

Things are little better elsewhere. Apart from a handful of works – the concerti, the magisterial Piano Sonata in B Minor, one or two of his symphonic poems (a genre Liszt invented) – he struggles to make it onto concert programmes in almost every setting. Large-scale masterpieces like A Faust Symphony and the oratorio Christus are performed seldom, while recitalists stick to well-trodden repertoire and ignore the riches beyond – waltzes more fascinating than Chopin’s, lieder as haunting as Wolf’s, and character pieces foreshadowing Debussy and Ravel. Classic FM plays a handful of hits like the third Liebestraüme, but ploughing such a narrow furrow merely reinforces the impression that these are the only things worth hearing.

How did it come to this? How has one of the nineteenth century’s most daring innovators fallen into such neglect? One reason could be old-fashioned snobbery. For Ivan Hewett, writing in the Telegraph recently, we’ve never quite known what to do with Liszt’s extravagant posturing, lurid personal life, and manifold contradictions – ‘half gypsy, half Franciscan monk,’ in Liszt’s own words. Praising his generosity of spirit, Hewett declares: ‘I can’t think of any great composer I would rather have dinner with.’ But table manners only go so far: Hewett volunteers that a handful of Liszt works bear comparison with Chopin or Beethoven, but qualifies this by citing ‘the far more numerous pieces stuffed with glissandos and impressive leaps, but no actual music content.’

The quality control critique undoubtedly does apply to Liszt – it would be surprising if it didn’t, in a canon of nearly 3,000 compositions – but judging artists by their poorest works is an unwise expedient. (We don’t think any less of Beethoven for his Battle Symphony.) It’s worth noting, too, that Liszt was his own worst critic, frequently revising earlier pieces to the extent of creating entirely new compositions. Partly because of this inveterate process of improvement, Liszt’s roster of masterpieces is rather larger than Hewett allows. Yet the welter of genres, styles and elaborate titles that characterise Liszt’s oeuvre, compared to, say, Chopin’s neat groupings of nocturnes and mazurkas, don’t exactly make things easy for newcomers.

Liszt once remarked of Beethoven: ‘to play [him] well, a little more technique is required than he demands’ – but this also applies to his own works. Virtuosity is central to his aesthetic. But Liszt also needs a pianist who can resist the temptation to display their technique instead of letting the music sing. (Jorge Bolet, in his Decca recordings, shows the way here.) Liszt relies on humility in the performer – not something virtuosi are famous for.

Perhaps we find Liszt difficult to place because he was such a great pianist. We might naturally think that rules him out from being a great composer – especially when he was also a superlative conductor, writer, teacher, administrator, correspondent, traveller, and bon vivant. As musicologist Kenneth Hamilton put it, ‘the greatest source of wonder in Liszt’s life was that he composed anything at all, let alone anything of lasting greatness.’

Perhaps we also struggle with Liszt because he challenges us to step beyond restricted ideas of greatness. Liszt was no single-minded hermit, moving with somnambulistic certainty towards narrowly conceived goals – but maybe that adds breadth, not shallowness, to his works. We can rail against the flamboyant virtuosity and showmanship, or we can relax and enjoy Liszt’s dazzling pianism and cosmopolitan élan; we can criticise the Hungarian march that intrudes upon the Second Piano Concerto, or we can look beyond to the crystalline perfection of ‘Au bord d’une source’, the visionary landscapes of Après une lecture du Dante, or the prophetic, sun-drenched impressionism of ‘Jeux d’eaux à la Villa d’Este’. In the end, there are many Liszts; it’s up to us which one we want to keep.

Comments