This is a curious book, by turns profound and whimsical. Karl Schlögel, a professor of Eastern European history at Frankfurt, begins by stating he didn’t know anything about his chosen subject of perfume beyond going into department stores and duty-free shops to encounter a ‘peculiar mélange of scents… the light and sparkle of crystal, the rainbow of colours, mirrors and glass’. Although he always felt this to be an alien environment, he was also repeatedly captivated. Then by chance he discovered a link between Chanel No. 5 and the Soviet perfume Red Moscow. Intrigued, he went on an intellectual journey to find out the shared and distinctive histories of France and the Soviet Union in the 20th century, from the novel point of view of the creation, distribution and marketing of fragrances.

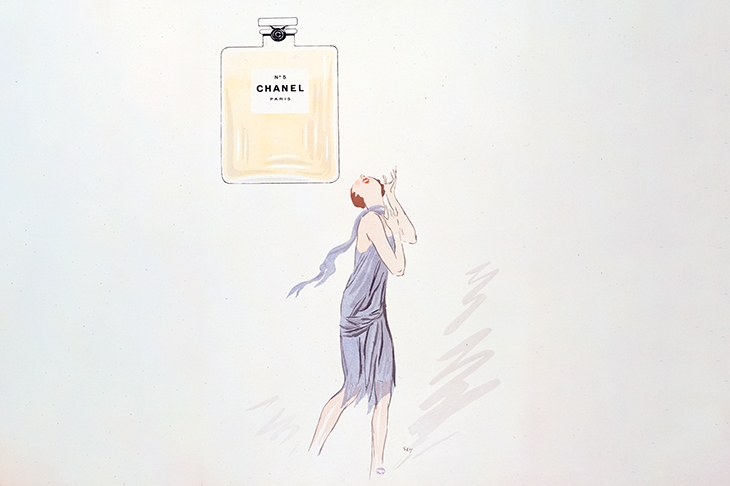

The result is a delight to read, if also ultimately mystifying. Schlögel describes how in Tsarist Russia, two French perfumers, Ernest Beaux and Auguste Michel, worked on related fragrances to mark the 300th anniversary of the Romanov dynasty. Then, in the wake of the revolution, Beaux fled Russia for France, where he developed Chanel No. 5, while Michel remained, creating the very similar Red Moscow: two perfumes, one signifying self-expression and hedonism, the other ideal womanhood and female solidarity. Though politically divided, France and the Soviet Union were thus united on the level of fragrance, thanks to the creative alchemy of Beaux and Michel’s earlier work. From this base the author weaves in Russian ballet, 1920s fashion, socialist realism and the Russian avant-garde in Paris.

But, disappointingly, we learn little about the two perfumers. For Michel, the primary sources are lacking. He stayed in the Soviet Union because his French passport was ‘lost’, but we don’t know why or how, nor what happened to him after the late 1930s. Schlögel hints at a grim fate during Stalin’s purges; but there are no documents or eyewitness accounts, and so Michel simply vanishes. Beaux, meanwhile, mixes a range of perfumes in his French laboratory and presents a series of them to Coco Chanel, who chooses the fifth — hence Chanel No. 5. After that he too is out of the story.

The book covers a range of other personalities. We meet Diaghilev, the Soviet foreign minister Molotov and his wife Polina Zhemchuzhina, who helped to build the Soviet perfume industry; even Churchill gets a look in, as Coco Chanel’s friend. But beyond noting how these people moved in the same interconnected worlds, the point of how they relate to Chanel No. 5 or Red Moscow isn’t always clear.

Schlögel is superb, however, in his account of what he calls ‘scentscapes’. He advocates for a historiography revolving around the world of smell. This is a fascinating and much neglected area, since history is largely built on the word and the image: documents, texts, paintings and so on. Moreover, Schlögel is right to note that in the hierarchy of senses smell is traditionally at the bottom: ‘It stands for all that is non-conscious, unconscious, non-rational, irrational, uncontrollable, archaic, dangerous.’ He argues that a revision of the order of the senses, bringing smell higher in the rankings, can reveal much that traditional historiography has skimmed over or banished.

Chanel No. 5 signified self-expression and hedonism, Red Moscow ideal womanhood and female solidarity

The vision is poetic: the simplest trace of a known smell could set us off, Proust and madeleine-like, into long, rich interior worlds, full of the way the past actually lives in us. Even though The Scent of Empire has an unsteady grip on its subject, I buy its vision of scentscapes: a splendidly pungent area for exploration.

Comments