Standing on a cliff edge looking at where the Blue Nile is just a trickle, watched by a gelada baboon on a distant rock and staring over miles upon miles of some of the most beautiful countryside I’d ever seen, one thought struck me: why is there hardly anyone else here? Ethiopia is stunning to look at, once you get out of the capital, Addis Ababa. It offers history, culture, architecture, religion and everything in between. Yet when you tell anyone you’re going there the most common response is: ‘Really? Why?’

In a country twice the size of France and with a population of 120 million, there were times when I felt I was the only tourist in town

In a country twice the size of France and with a population of 120 million, there were times when I felt I was the only tourist in town. Perhaps it’s the hangover of nearly 40 years ago when the images of starving children dominated the headlines around the world and led to the unprecedented international effort of Live Aid. But that was then. When I went the news in Britain was about a shortage of tomatoes, but there were stalls packed with them in Addis (I’m told that’s the in-the-know way to refer to the city).

The plane to Addis Ababa was packed, but on arrival it turned out that the vast majority of passengers were not stopping but transferring on to flights heading to Eritrea, Kenya, Nigeria and anywhere but Ethiopia, this largely forgotten gem in a continent famous for diamonds.

It’s a shame but not surprising. After two years of Covid keeping tourists at home, there followed two years of a brutal civil war that saw an estimated 600,000 deaths and shocking reports of rape, torture and other atrocities. A peace deal with rebel forces, signed in November, is holding up, just, but some governments are still advising their citizens not to travel here. And even if this wasn’t the advice, it’s debatable how many more Americans, Europeans and others with cash to spend would come.

So why did I choose to spend a few days here, on my own? The answer to that is easy. It’s a beautiful country, the cradle of civilisation, the place where coffee was discovered, one of the oldest Christian nations in the world; it offers world class scenery, active volcanoes, unique wildlife and is dirt cheap once you get there. Even the weather was agreeable when I visited, hot but not baking in the day and cool but not freezing at night.

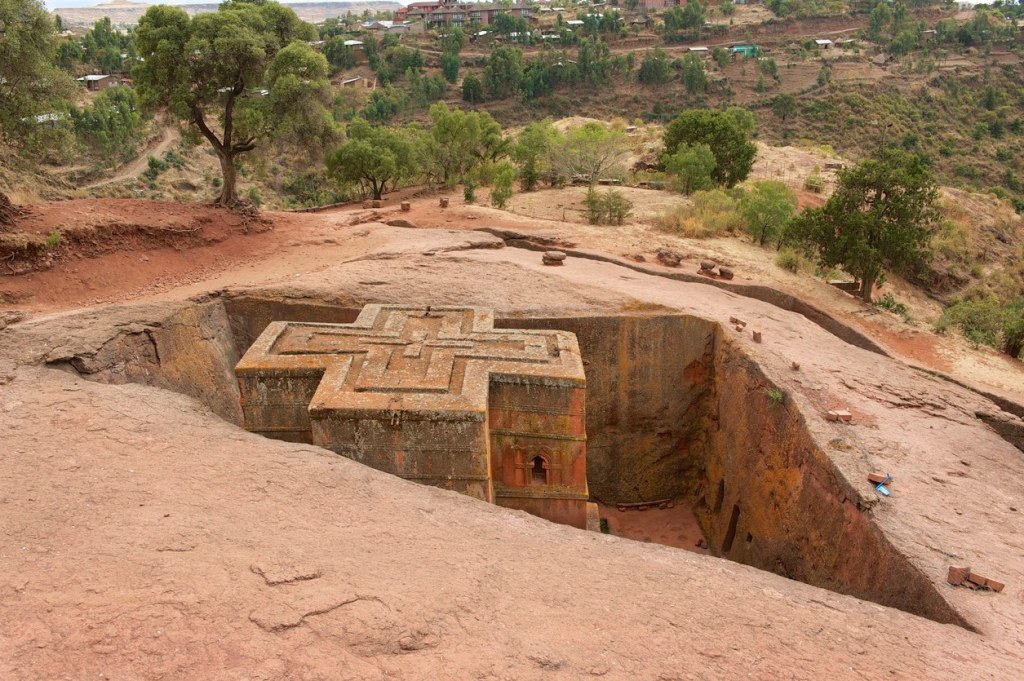

But my main reason for going was to see Lalibela, a short internal plane ride from Addis, where there is a truly remarkable collection of around a dozen churches built from the top down out of the rock. They call it the ‘African Petra’, but unlike the Jordan tourist trap it has not been blessed with appearing in an Indiana Jones film, so there is a surprising lack of foreign visitors. This makes it very easy to be guided round these monolithic monuments to Christianity, some of which date back 900 years and contain some of the oldest handwritten bibles in the world. These are working churches with priests, pilgrims and disciples around and during mass, literally hundreds and hundreds of white robed devotees gathering inside and outside.

Being one of the very few white faces in town, you tend to get people coming up and talking to you – and not just to ask for money or a pen (or, in one case, a reference for college). They want to tell me how their government is not helping them, how they feel ignored and the trouble they have finding jobs. One youngster invited me to his school, where I spoke to the headmaster and various other teachers. Many of their sixth formers were going on to college, mostly to study tourism so they could become guides, but they were worried there would be more guides than tourists if things didn’t change.

It seems churlish to complain about a lack of tourists when it affords such laid-back and uncrowded attractions, but Lalibela relies on overseas visitors to the extent that tourism accounts for 85 per cent of its income. The town is on its knees. Surviving restaurants are practically empty. Our hotel – a small guesthouse with immaculately clean rooms and first-class service – had just three guests, all solo travellers. Apart from me there was a retired Spanish bank manager from Benidorm and a Canadian health and safety officer who was YouTubing his way round the world, filming himself in various countries. Oh, and it cost around £30 a night to stay.

Lalibela’s rock-built attraction thinks of itself as the eighth wonder of the world and it certainly ranks as a sight worth seeing. It’s easy to get to by air (not quite so easy if taking the 30-hour road trip), there’s plenty of cheap but good accommodation and it feels safe and friendly, even when walking home down pitch-black streets.

I went into a bar and found a bottle of St George’s beer (he’s a big-name saint there too) costs around £1.30 at current exchange rates. I was the only westerner in there but was warmly welcomed. Street sellers offer coffee fresh from the country where it originated for the equivalent of 20p a cup and strong, local tea for just 30p. Even a packet of cigarettes is less than £1.50, though surprisingly few people smoke. A former soldier I shared a cigarette with told me women weren’t allowed to smoke, though he rolled his eyes as he added: ‘But they do in Addis.’

That’s pretty much the picture throughout the country, it seems. Addis is a dirty, bustling, chaotic city of ten million with shops, restaurants and bars, yet even there prices remain low. I would say the capital is not much to write home about, but it has some attractions – notably the skeleton of Lucy, the oldest human remains ever discovered and which gave the Ethiopian tourist authority the catchy slogan ‘Land of Origins’. There is also the fascinating museum that was once the palace of Emperor Haile Selassie, built in the grounds of the impressive university.

But the best of Ethiopia lies outside the capital. A two-hour drive over some atrocious roads takes you to the source of the Blue Nile where the gelada baboons – or bleeding-heart monkeys – watch from nearby cliffs. The route there passes through towns and farming areas where a sea of corrugated metal roofs, lack of electricity and traditional mud huts remind you that this is still a very poor country.

Live Aid’s money and other funding has created vast areas of fertile land, a new (though controversial) dam to irrigate dry areas and better farming practices, but it clearly still needs the kind of boost tourism gives. And for a destination that promotes wildlife watching as one of its main attractions, it seems a bit self-defeating to confiscate binoculars from tourists as they enter the country. All I was told when I asked why they took my pair was ‘security’. I got them back on leaving.

It may take more than one visit to feel one knows the country. It would take years to learn Amharic, the local language where the word for ‘thank you’ is six syllables long. But as I left, I could not help thinking I would return. To coin an old joke, it was not so much goodbye, more Abyssinia.

Comments