Few things sum up the chasm between childhood and adolescence more poignantly than our changing relationship with music. One minute life is all familial cuddles and nursery rhymes – the next it’s all parental alienation and rock’n’roll. One year I was eagerly buying the records of Pinky & Perky, the next those of Dave Dee Dozy Beaky Mick & Tich – and the next, the records of the Velvet Underground and Nico.

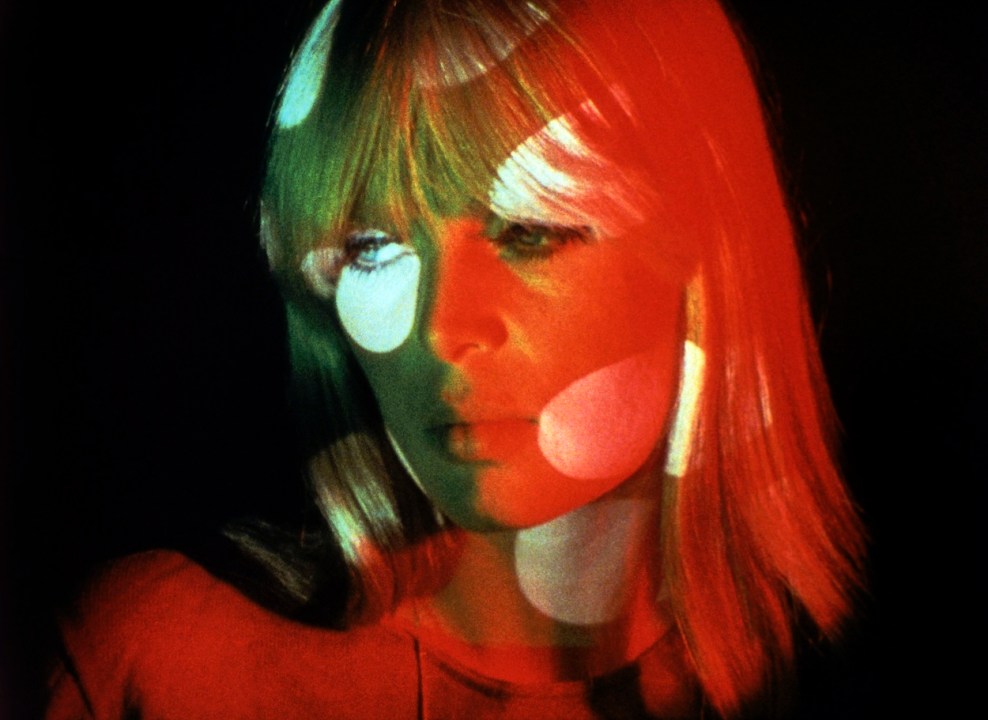

Nico had finally found the family’s piano and was pumping away on it as if her life depended on it

My relationship with Nico – the fantasy and the reality – is one of the funniest never-meet-your-heroes experience I’ve ever had. She came to mind recently because – of all the unlikely singers who might be used to soundtrack commercials – she’s been featured in two TV adverts. One for the fashion house Prada (singing ‘My Funny Valentine’) which seemed appropriate, as the po-faced suffering-is-beauty ethos of haute couture – those catwalk mannequins would rather break a leg than smile – is perfectly in line with her doomy music. Far odder was her popping up singing ‘I’ll Be Your Mirror’ for the travel company Expedia earlier this year – at the Super Bowl, no less, soundtracking the wholesome trip of three generations of females from the same family who go to see the Northern Lights. Her booming baritone also cropped up on the Netflix smash One Day, sounding strange among all the cheery 1990s indie-pop, singing the Jackson Browne song ‘These Days’; one of the saddest songs about world-weariness ever written, not least because the composer was only 16 when he wrote it. Nico herself was not yet 30 when she recorded the song for her first solo album Chelsea Girls in 1967 but whereas it might have seemed a bit of a stretch for a teenage boy to have accumulated so many regrets, it was totally believable that Nico might have lived nine lives while still in her twenties. ‘Experienced’ is the word above all that comes to mind when one thinks of her; reading her Wikipedia page brings on a feeling I can only describe as vertigo – and I’m no shrinking violet.

Born Christa Paffgen in Cologne in 1938, her father died while fighting with the Nazi army; her mother took her to live in Berlin after the war, where she became a model by the age of 16, renamed ‘Nico’ by a gay photographer after a lost love. Very tall, with cheekbones which looked like some elaborate hoax, she was one of those women whose beauty when young must feel like trying to keep control of a carriage pulled by four wild horses; her life from this point was the stuff of grim fairytales, and make the average name-dropper look like the original one horse from a small town. She began the 1950s modelling in Paris where she claimed to have had sex with Jeanne Moreau and Ernest Hemingway – there’s no proof, but when you look like that, nothing’s impossible, nooky-wise – and ended the 1950s in Rome where Fellini cast her as a model named Nico in La Dolce Vita; she was literally playing herself. Then in the 1960s, she moved to New York, where she became a junkie.

I’d like to say a few things about heroin here. First, it’s rubbish – the only time I took it, it was like standing in a queue and enjoying it. Second, there’s no such thing as addiction – not to pornography, not to drugs, not to alcohol – there’s only habituation and our own laziness about breaking bad habits. (If there’s such a thing as addiction, how come that almost a decade ago I stopped taking cocaine after 30 years of daily use and never craved it again?) Thirdly, all junkies are the same person.OK, so all drugs can be generalised about; too much alcohol makes you boring, too much marijuana robs you of your ambition, too much cocaine makes you talk rubbish. But people who indulge in all these drugs still retain some measure of their pre-drug personalities; with a very few exceptions, junkies are the same person – their life is about just that one thing. It’s ironic that a lot of them see taking it as the most rebellious thing one can do, when heroin is the only drug that the state will give you a substitute for; in my coke-fiend days – during most of which I was paying the top whack of tax – it used to make me fume when I’d walk into a chemist and see some junkie being given a little cup of their drug-of-choice substitute. Why wasn’t the state giving me a cocaine-substitute so I’d work even harder and pay even more tax? I see now how impracticable this was – people should pay for their own recreational drugs – but I still believe that if the state stopped doling out downers and started handing out amphetamines again, we’d have the lazy legions of shirkers back to work in no time – and they’d lose weight without expensive semaglutides. I remembered how flattered daft English punks were when the Yankee band The Heartbreakers moved to London in the late 1970s, believing that they’d transplanted themselves because ‘the scene’ was so much more vital here. In fact, they came because the NHS was notoriously generous with the smack-substitute. Jerry Nolan of The Heartbreakers said of the band’s London sojourn ‘everything we did revolved around drugs’ and this is one of the reasons I stopped taking drugs – not how expensive it was or over health issues. Habits which once seemed to open the world can shrink it down as the decades pass by and rather than shoot for the stars, you simply stay indoors, dreaming of leaving. The junkie’s world becomes a rat-run, and access to their poison the whole point of their lives.

Anyway, back to my cautionary tale. In 1984, aged 25, I left my first marriage and small son and ran away with a young American, scion of a strange bohemian family. We briefly lodged with them in the Angel and I grew used to exotic waifs and strays turning up late at night in search of distraction. But you could have knocked me down with a hypodermic needle when who should waltz in but the heroine of my girlhood, Nico. She’d moved to Manchester – where heroin was notoriously cheap – a few years before and was now living (platonically) in Brixton with the poet John Cooper Clark. ‘Who wouldn’t like to think you were with one of the ten most beautiful women in the world, official – and that was in the day of Brigitte Bardot and Julie Christie,’ he told the Guardian in 2012. ‘But we were junkies so it (sex) doesn’t really come up. It’s not a physical world. It’s just not a sex drug, heroin… it was a feral existence.’ After the NME published a photograph of them together ‘a tidal wave of junkies arrived’ leading Clarke to eventually clean up his act. JCC was a friend of my mother-in law – they were both poets – and I grew used to seeing him around. He was a lovely fellow. Imagine my surprise when one night, he walked in with Nico. Naturally, I was too tongue-tied to speak to her; I quickly left the room and went to my boudoir to have a fit.

Over the next few months, Nico became a familiar face at the homestead – yet I never once spoke to her until one fateful night. The main reason for this is that she was without doubt the most self-centred and boring famous person I’ve ever met. It was that rat run thing that drugs do to your mind – and in Nico’s case, literally and physically. The woman whose life had read like a perfume bottle since an early age – Paris, Rome, New York – now had one place on her mind: Stoke Newington, where her dealer lived. That operatic Germanic voice, once crossing oceans, could regularly be heard wailing ‘I need a lift to Stoke Newwwington!’ With all respect to Stokey, it wasn’t where I’d imagined her as an adoring teenager. She befriended my mother-in-law, if ‘friend’ is a word you can ever really use of junkies, because they don’t have friends, they have people they scrounge off. ‘Fran, lend me a tenner and I’ll pay you back that fiver I owe you’, was a frequent request. ‘Why don’t you ever talk to Nico?’ Fran said once. ‘She thinks you don’t like her.’ Well, I didn’t. But I still kind of loved her – so I couldn’t talk to her.

Until one night I finally did. I was trying to get to sleep in the small hours when the most awful noise came from the living room directly above. Nico had finally found the family’s piano and was pumping away on it as if her life depended on it. I was hearing Nico sing – live, at last – with only a few planks of wood separating us. I stayed stock still, listening for the song… it was ‘Janitor of Lunacy’, my favourite as a teenager. I began to sing along softly – it was a magical moment – ‘Janitor of lunacy/Paralyze my infancy…’ Then I snapped out of it; I had a deadline that morning – and unlike the yodelling Kraut upstairs, I was a professional. So I got out of bed, went to the foot of the stairs and shouted as loud as my voice would go ‘Oi Nico – shut that bloody racket up! There’s people trying to sleep.’

The door closed quietly awhile later; I never saw her again. A few years later this creature of the night went out in the mid-day sun of Ibiza on the hottest day of the year looking for drugs and died of a cerebral haemorrhage after being knocked off her bike by a random motorist. This woman who had been the toast of three continents was found lying by the side of the road by a kind passing taxi driver, but his efforts were complicated by the fact that local hospitals did not want to take her. She was cremated in a forest cemetery in Berlin, to the sound of her own song ‘Mutterlein’.

Personally, I believe that no one’s lived such a bad life that they deserve a Nico song at their funeral – not even Nico. She was a nasty piece of work, but she was a fascinating character – the two often go together, a fact which bed-wetters bleating about kindness will never comprehend. By trying to make our cultural icons nice, we fail to appreciate their power, seeking to cut them down to size lest they scare us with their not-niceness and all that problematic stuff. Nico was racist, sexist, snobbish, anti-Semitic and lazy – but she was also a legend of the kind I doubt we’ll ever see again, a vile and beautiful product of the 20th century in all its trauma and glamour. She’ll never be castrated by inappropriate empathy or domesticated by Expedia commercials. For that, I can respect – if not admire – the monstrous idol of my youth.

Comments