I miss kippers. My wife won’t let me eat them at home, and they have become a rarity in restaurants. I stayed in a luxury hotel last month, and the manager was telling me that if I wanted anything – valet parking, room service, breakfast after 10.30 a.m. – I had only to ask. When I enquired if kippers were on the menu, he went as white as unsmoked cod and mumbled that the head of housekeeping had forbidden them because of the luxury soft furnishings.

But I have medical science on my side: a report in the British Medical Journal last week said that fish such as herring could save lives, and the planet. Nearly three-quarters of forage fish – those half-way up the food chain, between plankton and larger fish, like tuna or cod – that are caught are not eaten, but made into fish meal for farmed fish like salmon. Cutting out the middle-fish and eating forage fish themselves would be more efficient, sustainable and – because they contain omega-3 fatty acids – could save 750,000 lives if they replaced red meat in our diet. Also – and it’s a shame the scientists didn’t make more of this – herring tastes better than farmed salmon, the most boring fish on the market.

One of the problems is that these fish do not last: those who bought fresh herring from cadgers before refrigerators found that it was inedible as often as not, which is why ‘cadger’ now means ‘someone who gets something for nothing’ rather than its original meaning of ‘a hawker of fish’. The only way to keep herring edible, if not palatable, was by heavily salting the fish and smoking it for nearly two months. The herring took on a red colour and a smell so overpowering that foxhounds could be put off the scent – hence the term ‘red herring’.

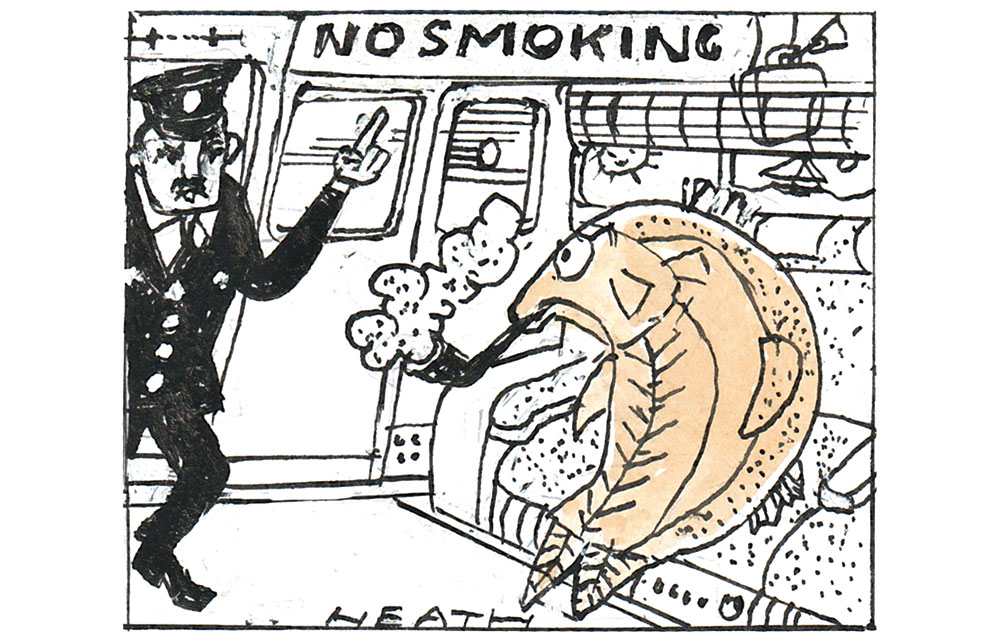

The kipper was an invention of the railway age. When inland cities could be reached in hours, herring only needed to be lightly salted and smoked. The more romantic story is that in 1843 John Woodger in Northumberland split and gutted a herring ready

for breakfast and left it overnight near a smoking stove; the result was so delicious that he had to share it. His smokehouse – conveniently enough, he had one handily situated for both the fishing village of Seahouses in Northumberland and the North-Eastern Railway – is still in operation.

Now, as then, the herring are ‘cold smoked’ – placed at a distance from a slow-burning fire, fuelled by sawdust and woodchips. Oak is best, but some smokers cut it with other wood; as long as there is some oak among the deadwood it can be described as ‘oak-smoked’. This seems less of a cheat than the first world war trick of painting kippers with a dye made from coal tar to cut the time spent in the smokehouse.

This wartime expediency was the beginning of the end of the kipper. From its place on every Victorian and Edwardian breakfast table, it became the food of the poor – George Orwell writes in The Road to Wigan Pier about a supper of kippers and strong tea – and the Ministry of Agriculture was worried about what to do with all the herring. Civil servants wanted to distribute it free to schoolchildren – this is what they’d done with the oversupply of milk until Mrs Thatcher snatched it away – but the minister refused, saying: ‘You cannot feed necessitous children on raw salt herring. I can imagine nothing which would upset a child more.’

The Herring Industry Board lasted until 1981, when Mrs Thatcher got rid of it too. I hope the BMJ’s scientists have more success.

Comments