In his first speech of this election campaign, Keir Starmer made what is likely to become an extremely familiar claim. Focusing on the concerns of those who abandoned Jeremy Corbyn’s Labour for Boris Johnson’s Conservatives in 2019 he argued that voters could trust him with the economy as well as Britain’s borders and security ‘because I have changed this party permanently’.

As leader, Starmer has certainly sought to distance himself from the policies and personnel and even imagery of the Corbyn leadership. He talks about his patriotism, surrounds himself with Union Jacks, has rowed back from commitments to nationalise various industries and has become much more friendly with business while expunging the party of the taint of anti-Semitism.

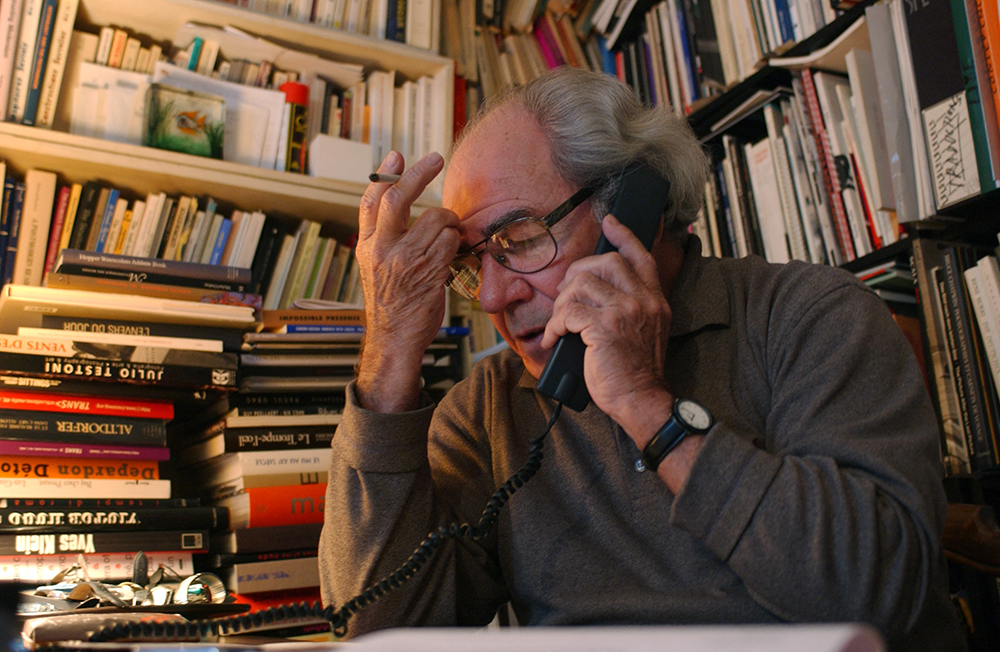

It is only a bold or foolish leader who thinks they can impose their will on Labour

Some claim he also used unfair means to purge the party of Corbyn supporters and prevent them from becoming candidates, as has been the case with Faiza Shaheen and Lloyd Russell-Moyle this week. Starmer’s approach over the past few months has led to thousands of Corbyn supporters voluntarily leaving the party, notably and most recently the columnist Owen Jones who argued that Labour under Starmer had become a hostile environment for those wanting ‘real change’.

Starmer’s case for having significantly changed the party is, then, strong. But can he really claim this is a ‘permanent’ transformation? Looking at the party’s history, it is only a bold or foolish leader who thinks they can impose their will on Labour – even just for the foreseeable future.

In the early 1980s, with Labour in opposition, supporters of Tony Benn amended the party’s constitution to take power away from MPs and give it to members and the unions, believing this would turn it into a fully socialist party. After MPs lost their exclusive right to determine who should be leader in 1981, some on the right thought the game was up and left to form the Social Democratic party. Even so, the first leader elected under the new franchise was Neil Kinnock, who made it his business to chart a course back to the centre ground and isolate Benn. In fact, when in 1988 Benn stood for leader hoping to usurp Kinnock, under the system he thought would transform Labour, he was humiliated with just 11.4 per cent of the vote. Feeling they had been definitively defeated, a steady stream of Bennites started to leave the party just as some Social Democrats made their return.

Kinnock’s moderate course was continued zealously by Tony Blair whose ascent to the leadership in 1994 was taken by supporters as the ‘Year Zero’ in the making of a new party. To symbolise the creation of New Labour, Blair revised Clause IV of the party’s constitution which since 1918 had committed it to the extension of public ownership. As he wrote in his memoirs, Blair believed that by striking down this ‘graven image’ he would transform the party’s psychology. Certainly, some on the left thought Blair had destroyed the party they loved. In response Arthur Scargill formed the Socialist Labour party, with the old clause IV taking pride of place in the new party’s constitution.

Corbyn’s election as leader in 2015 on what was essentially an anti-Blair platform suggested New Labour had not changed the party’s psychology for good. Indeed many of those who took a prominent role in the Corbyn leadership were veterans of the earlier Bennite period. They had emerged from the ‘sealed tomb’ to which Peter Mandelson reputedly hoped the hard left had been assigned forever.

There are those in the party who today believe Starmer is ‘not just sealing the tomb but incinerating it as well’. Certainly, Starmer has introduced changes that make it almost impossible for a hard-left candidate to replace him as leader. And it is likely the parliamentary party after the election will be packed with an unprecedented number of loyalist MPs. There will be leaders of key unions, notably Sharon Graham of Unite, who will try to ensure a Starmer government stays true to its promises to introduce new employee rights. And despite the best (if bungling) efforts of his allies, Prime Minister Starmer might still have to listen to his government being attacked from the back benches by Diane Abbott, should she decide to seek another term as an MP. But most party members will be willing to remain quiet despite any misgivings, happy to see their party in power after a decade and half in opposition.

The last 50 years of Labour history suggest this happy state will not last forever. Starmer’s dominance currently looks secure but how long it lasts depends on his success in government and in the polls. It easy to forget that in 2021 Starmer came close to resigning after a series of bad election results in the spring: had he lost the Batley and Spen by-election a few months later he might have been forced to go. Labour’s subsequent transformation in the polls – massively helped by Conservative failings – strengthened his own position and that of his chosen moderate course for the party.

Starmer is by hardly widely loved in the party and lacks a cohort of committed ‘Starmerites’ at the top: support for him, like all previous Labour leaders, depends on results. So if things go wrong in office he will likely become vulnerable again, the party will cast around for a change of course and Labour’s rollercoaster ride will resume.

Comments