Members and supporters of the Conservative party do not generally speak in favour of proportional representation (PR) – which is hardly surprising given that the current system has given them 49 out of the past 79 years in power. There are exceptions: Ferdinand Mount, head of the No. 10 Policy Unit under Mrs Thatcher, briefly advocated it during the Conservatives’ long period out of office in the 2010s before changing his mind after the Conservatives returned to power. In a debate in 2019, Conservative MPs Dan Poulter (who defected to Labour earlier this year) and Derek Thomas spoke in favour.

Whatever the iniquities of this week’s result, Conservatives should plot a path back to power within the current system, not seek to change it.

Come Friday, there may be rather more Conservatives toying with supporting the idea – especially if the very worst projections come true and the party finds itself with even fewer seats than those serial advocates of PR, the Lib Dems. Under PR, it is not impossible that the Conservatives could cling to power after the election in a coalition with Reform – although the greater likelihood would be of a Labour-Lib Dem coalition. There will be even greater demand for PR from Reform, who have been predicted to win upwards of 15 per cent of the vote on some polls while winning hardly any seats. Reform may well find itself in an unholy alliance with the Lib Dems in demanding electoral reform.

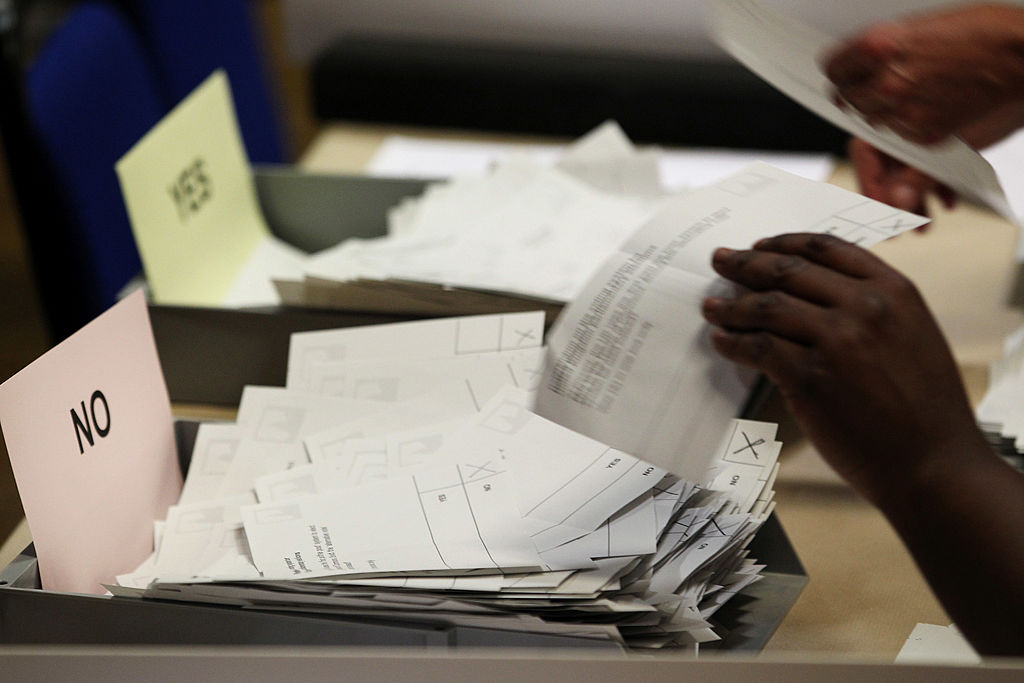

True, the outcome of this general election could turn out to be even more lop-sided than Mrs Thatcher’s biggest victories. Some polls have Labour winning a 250-seat majority on less than 40 per cent of the popular vote. Yet the cry for PR is, nevertheless, one which needs to be resisted. This is not least because the public rejected a mild form of electoral reform – the alternative vote – by a two-thirds majority in a referendum 13 years ago. Anyone demanding change in the electoral system now would put themselves in the same boat as Nicola Sturgeon, who spent all her time as SNP leader demanding a second Scottish independence referendum. Once the people have rejected – or approved – something in a referendum that should be the matter closed for at least a generation.

One especially unappealing aspect about PR is that it would mean voters could no longer pass judgement on individual MPs. In a wretched party list system, we could never have moments like Neil Hamilton’s defeat by Martin Bell in 1997. MPs elected under PR would only have to curry favour with their own party officials – after which they could hide behind their party’s popularity. By-elections would become redundant because any MP who died or resigned could simply be replaced with the one next down on the party list. No MP would have a personal mandate. We would lose the independent-minded MPs like Bill Cash or the late Frank Field, who were able to build a personal followings among their constituents. There might be a greater diversity of parties in government, but it would only come at the cost of far greater centralisation of powers by political parties. Party lists would inevitably be drawn up in Westminster, away from local constituencies.

The British public have shown many signs of being disenchanted with their politicians in recent years, but PR would do nothing to resolve the problem. On the contrary, it would exacerbate many existing problems: our MPs would be more remote and more Westminster-centric. Whatever the iniquities of this week’s result, Conservatives should plot a path back to power within the current system, not seek to change it.

Comments