Andrew Lambirth on the special relationship between the artists Zoran Music and Ida Barbarigo that is explored in an exhibition that shows their work together for the first time in more than half a century

At the Estorick Collection, a modest north London townhouse, there is until 12 June a most engaging exhibition devoted to two artists, husband and wife, whose work is not particularly well known in this country, though both are recognised and celebrated internationally. Ida Barbarigo (born Venice 1925) first met Zoran Music (1909–2005) at an exhibition of his paintings in Trieste in the spring of 1944. Their burgeoning friendship was interrupted when Music was arrested by the Nazis, who first accused him of spying and then wanted to recruit him. He refused and was deported to Dachau.

Zoran’s horrific experience at Dachau scarred his mind and his creative imagination, and was only to surface years afterwards in his work. As he said much later, ‘Even now the eyes of the dying are still with me.’ In 1945 he was able to return to Venice (where Ida was living), but it was not until 1971 that he began the great series of images collectively entitled ‘We are not the last’ about his concentration camp experiences. He always said that without Dachau he would have been an illustrative painter: internment made him go to the heart of things.

Ida, meanwhile, had been pursuing her own artistic trajectory. From a very early age, she was haunted by a sense of destiny — that she would grow up to be another Leonardo or Christopher Columbus. After toying with the idea of becoming a musician (she learnt classical guitar), or an architect (she made very precise drawings for an architect uncle), Barbarigo decided to capitalise on her innate talent for drawing and painting. She studied at the Accademia with her adored father, who was professor of painting there, but the academic training was more than a little tedious. Her father dealt intelligently with her need to rebel. ‘If you don’t feel like working, don’t bother,’ he would say. ‘Go and have a coffee on the Zattere.’ Ida felt liberated: ‘I loved the whole feeling of freedom and light and movement you got the moment you were outside in Venice.’ And it was here no doubt that she felt the first stirrings of one of her most fruitful subjects — abandoned café tables and chairs which symbolise their fleeting occupants.

On a recent trip to Venice I had arranged to meet and interview Ida, but unfortunately she was unwell, and I had to make do with a guided tour of her magnificent apartment overlooking the Grand Canal, conducted by her friend and interpreter, the Venetian writer Giovanna Dal Bon. The rooms are filled with beautiful things: three massive plain glass chandeliers depend from the ceiling of the main chamber, there are lots of paintings and drawings, a room of etchings, and a flight of plump, slightly chipped plaster putti across one of the walls, made by various members of Ida’s family, Venetian artists for more than 500 years.

Her father, Guido Cadorin, was a distinguished modernist painter, and I note a striking depiction of the lagoon, a portrait of his mother (shown in the 1911 Biennale), and ceramics designed by him as well as textiles for Fortuny. (Guido, multitalented, also designed mosaics, and a feeling of these can sometimes be discerned in Ida’s work.) Ida’s mother, Livia, was a painter, too, and Guido’s favourite pupil, and there’s a display of her small poetic tempera paintings of trees in one of the rooms off the central studio/living space.

A mini-retrospective of Ida’s paintings was laid out on an avenue of easels, including several important pictures that will be lent to the Estorick’s exhibition. Among the newer works at the studio end of the apartment were a number of paintings featuring the ‘Terrestrials’, impish figures like clay models which represent the barbarian hordes of modern life. These are perhaps Ida’s demons — naughty but full of electricity, dancing and scuffling in fruitful ambiguity. (They could be tourists invading Venice.) In this room stand four of the celebrated café chairs from the Zattere, in red metal, wooden-slatted. ‘She used the chairs as a virus inside Venice,’ says Giovanna Dal Bon. Perhaps they played a similar role to the Terrestrials — a subversive agent, a way of commenting on the weight of Venice’s past while allowing a contemporary element to intrude, like yeast, and bring the city to life again.

The critic and curator Michael Peppiatt, who knew Zoran and Ida well and has written perceptively about their art, recalls that ‘whenever you went out with them, it was like being with the king and queen of Venice’. Peppiatt relished their grand hospitality and in particular their spectacular New Year parties. He describes Ida as ‘a bohemian aristocrat’. A beautiful woman, with more than a passing resemblance to the Italian film star Monica Vitti, she has enjoyed the admiring attention of many men in her life, including François Mitterrand, in whose presidential cavalcade Ida and Zoran would sometimes travel. (Music and Barbarigo used to live for half the year in Paris, though always returning to Venice.) Peppiatt also notes Barbarigo’s wicked humour, seen especially in the way she depicts sunbathers on the Lido as corpses washed up by the sea.

The relationship between Ida and Zoran was a very special one, an alliance based upon respect and distance. Although they married in 1949, as artists and human beings they pursued parallel paths, living separately and maintaining separate studios — until the last years of Zoran’s life, when Ida cared for him in her home — and meeting by arrangement for drinks and dinner. (Zoran would telephone to request the pleasure of Ida’s company.) Dal Bon describes Music’s dreamy and contemplative nature, his abiding sense of doubt, like a permanent trance, whereas Babarigo’s attitude is ‘one of natural ecstasy, out in the open, drawing on sudden enchantments, illuminations, details that “miraculously” move her and beg to be followed’.

Their different temperaments have resulted in very different kinds of painting, which are displayed together at the Estorick for the first time since a joint show in November 1946 in Trieste, when Ida was still known as Cadorina. (She adopted the pseudonym Barbarigo around 1950.) The Estorick exhibition, entitled Double Portrait, after Giovanna Dal Bon’s fascinating book about the couple (paperback, £35), tells the story of their life together, rather than comparing their work.

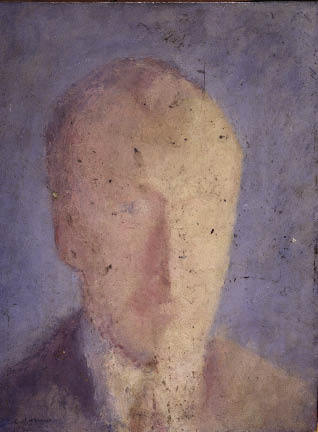

The exhibition is arranged in the two ground-floor galleries, with groups of evocative black and white photographs of the artists hung in the corridor between. There are flat cabinets of photos and documentary material, revealing the fundamentally intertwined and supportive temper of their existence. In gallery 1 are early portraits of each other, from the 1940s, and two later and more exploratory ones: Ida’s of Zoran from 1967, Zoran’s of Ida from 1988, both deeply moving. Here, too, is an early painting of chairs (1954) by Ida, in pronounced linear arrangements, striped like tram tracks, and one of Zoran’s beautiful landscapes with horses. In gallery 2 there is a polyptych of Ida’s ‘Terrestrials’ and a big painting by Zoran from 1989 of him and Ida in the studio. A later chairs picture, ‘Chairs Apart’ (1974), inspired by St Mark’s Square, shows Ida moving her linear investigations further towards form and mass, object and shadow, lyrically expressed. Her portraits, like the 1967 one of Zoran and the lovely painting ‘To Go to the Seaside’ (1966), are deliquescent, the paint very much on the move, dripping and melting with reflections. If Zoran’s art was a progression towards sil

ence, Ida’s is a dialogue which never grows less. Both deserve to be better known.

Comments