I’m autistic, I teach autistic children and I care for autistic adults, but I never kid myself that we are better than other people. When I asked a fellow autistic man if he could name any famous autistic people, he replied: ‘Hitler and Einstein.’ I love his answer because it punctures the romanticism around autism. There are evil autistic people, as well as geniuses.

Was Hitler autistic? We’ll never know for sure, but he showed several symptoms. People who met him found that once he started talking, he would not stop. He was also nocturnal, had an addictive personality and developed lifelong obsessions (in his case, racial purity).

Around half of all the people referred to the anti-radicalisation programme Prevent are autistic males. Are we more likely to become political extremists? Rachel Moseley, an autism researcher at Bournemouth University, told me that there was no evidence that autistic people are more likely to become radicalised, but they are more likely to be referred to programmes like Prevent. The reason, she said, is a ‘lack of a nuanced understanding of autism, so that certain behaviours and interests are easily misconstrued’. In 2002, Gary McKinnon, who is autistic, was accused of the biggest ever hack of America’s military secrets. He claimed he was looking for evidence of UFOs. The US authorities wanted to lock him up. A more intelligent response would have been to hire him.

Anyone diagnosed with autism should be reassured that life is getting easier for us, thanks to technology

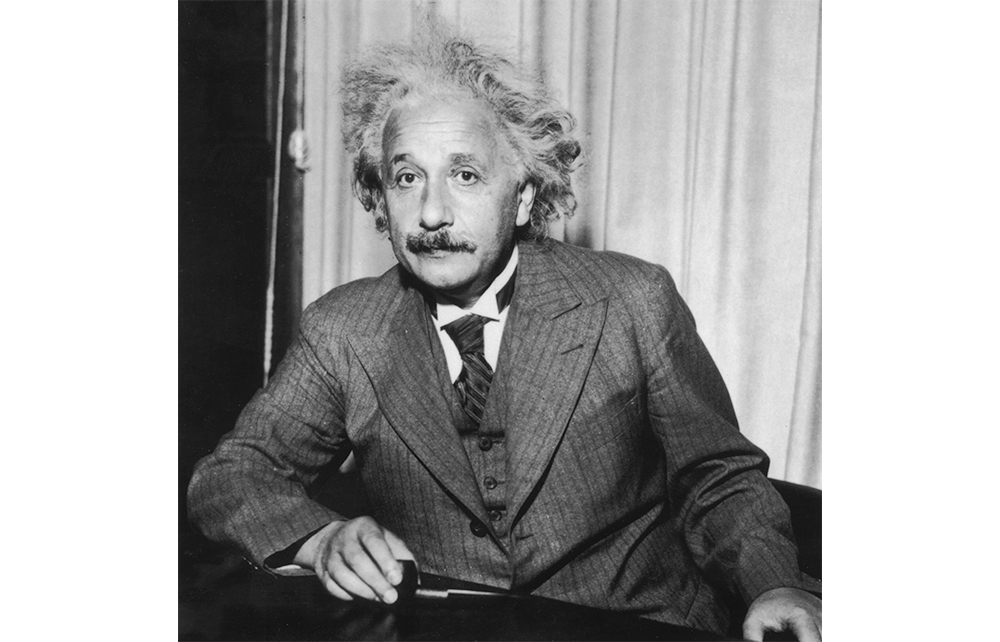

Was Einstein autistic? He did poorly at school except in the subjects that interested him: maths and physics. He and Ludwig Wittgenstein have been described as having Asperger’s syndrome, which is incorrect. Asperger’s is autism without speech delay, but Einstein and Wittgenstein didn’t start speaking until they were four and five respectively. The term Asperger’s has fallen out of favour now that we know Asperger collaborated with the Nazis’ eugenics programme.

I wasn’t diagnosed as autistic until I was 26 but I was sure I had it by the age of 19, when I read The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time by Mark Haddon. It is in my opinion the greatest fictional depiction of autism. Mark doesn’t have autism although he did teach autistic children. When he wrote about symbols getting jumbled up in the protagonist’s head, I knew I had the same condition.

I got diagnosed for a rather odd reason: I wanted to take part in experiments at the Maudsley Hospital. They hooked me up to EEG scanners and attached wires with bright lights to my head. I was also given experimental antidepressants. They asked me to do puzzles as I was put through an MRI. For £240, I was conclusively diagnosed and I also helped with scientific research. I couldn’t think of a better way to spend my time.

Earlier this year, the Nuffield Trust said the NHS couldn’t cope with the demand for autism diagnoses. The number of people wanting to see a specialist has risen five-fold since 2019. This may seem alarming, but anyone diagnosed with autism should be reassured that life is getting easier for us, mostly thanks to technology.

One common symptom of autism is dysgraphia or bad handwriting. Mine is terrible. However, thanks to keyboards, I have never had to handwrite a single article or CV. Video calls mean that those of us who are too anxious to travel can work and have meetings from home. We often struggle to recognise social hierarchies. Video-conferencing reduces this risk by enabling more egalitarian conversations.

If you want to experience autism in a crowded environment, try listening to several podcasts at once. We don’t have the ‘cocktail party effect’, that ability to filter out background chatter in a conversation, so we can’t control information that reaches our brains. If we hear something, we can’t help but focus on it, which can be frustrating and confusing.

Earphones have changed everything. Not only do they reduce sensory overload, but they also help reduce unwanted attention. How do they do this? A lot of autistic (and schizophrenic) people talk to themselves, usually repeating phrases they find amusing. This used to attract bullies but people now assume you’re talking on a Bluetooth earpiece if they see you talking to yourself.

Above all, it is the smartphone that has liberated us. My phone helps me to reduce sensory overload by allowing me to read white letters on a black background. This way, I can read for hours and my eyes don’t sting. Even illiterate autistics who I work with can use smartphones, thanks to the visual icons and voice-to-text technology. Those who can’t talk can use text-to-voice technology.

If autism were renamed ‘geek syndrome’, far more people would understand it. Geeks are socially awkward people with obsessive interests, a perfect description of autism. One reason autism is so common among computer programmers is that being a perfectionist is a bonus: one misplaced punctuation mark will ruin a line of code. ‘Geek’ was originally a term for people at funfairs who could tell you, for example, which day Christmas was in 1705. Some 10 per cent of autistic people have what are called savant abilities.

Speaking of labels, I wish we would stop using terms like ‘neurotypical’ for non-autistic people. There is a reluctance to use the word ‘normal’ to avoid making some people feel weird. But what’s wrong with being weird? Of course we are weird. We move our bodies when people don’t expect it. We get obsessed with things like tartan, Paraguayan history and giant tortoises. Thanks to modern technology, we can usually find someone else who shares our obsessions. If you’re autistic, obsessions are your life. Embrace the weirdness.

Comments