Photographs of roadworks feature regularly in the Hampstead Village Voice but, even with the postmodern fashion for grungy subjects, no contemporary residents have made paintings of them. Yet that, astonishingly, was what Ford Madox Brown did in the 1850s, lugging his two-metre canvas on to The Mount, off Heath Street, to do it.

Brown’s unlikely masterwork ‘Work’ was the first ‘Pre-Raphaelite’ painting bought by Manchester Art Gallery, where it is now the centrepiece of a major exhibition dedicated to the artist. I put ‘Pre-Raphaelite’ in inverted commas because Brown — a prickly individual with a deep distrust of all ‘Bodies, Institutions, Art unions & academies’ — was never strictly a member of the Brotherhood. So touchy was he that he even walked out of the official opening of Manchester Art Gallery in 1885 over the rejection of another painting, ‘Waiting’ — despite being then in the employ of the city. Manchester Corporation’s commission for 12 murals for Alfred Waterhouse’s new Town Hall kept him from starvation for the last 13 years of his life, but Brown never let personal advantage stand in the way of a good sulk or a sideswipe at civic pomposity. In his mural of ‘The Opening of the Bridgewater Canal’, he showed the teetotal Lord Bridgewater getting drunk.

Unlike the Academy-educated Pre-Raphaelites, Brown was born in France and trained to paint in the grand historical manner in Belgium. But a trip to Italy in 1845 with his consumptive first wife Elisabeth opened his eyes to the even light of the Quattrocento, and determined him to treat ‘the light and shade absolutely as it exists at any one moment, instead of approximately, in a generalised style’. While his lighting became Italianate, his inspiration remained resolutely British. ‘Oure Ladye of Saturday Night’ is an English Madonna performing the weekly nursery ritual of bath night, while ‘Work’ patriotically proclaims ‘the British excavator, or navvy…at least as worthy of the powers of an English painter, as the fishermen of the Adriatic, the peasant of the Campagna, or the Neapolitan lazzarone’.

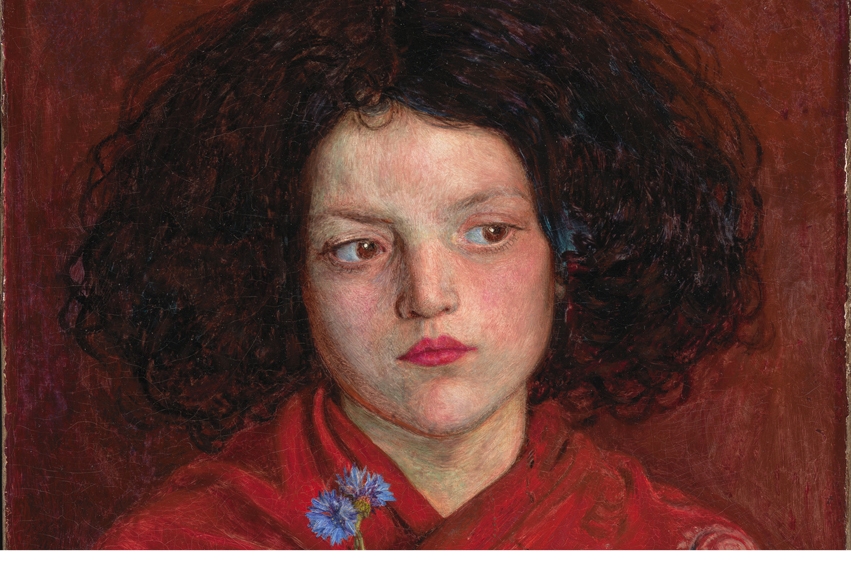

Brown’s new style attracted the admiration of Dante Gabriel Rossetti, who introduced the older artist to his Pre-Raphaelite friends. Under their influence Brown brightened his palette and adopted Ruskin’s gospel of ‘truth to nature’, taking it a lot too far for Ruskin who wanted to know why, in ‘An English Autumn Afternoon, Hampstead’, he had chosen ‘such a very ugly subject’ — to which Brown replied, ‘Because it lay out of a back window’. His flippant riposte belied the difficulty he had had in finishing it after his landlady reclaimed the room with said back window and obliged him to return the following autumn. Brown’s standard of truth to nature was far more exacting than Hunt’s or Millais’s. They added the figures to their plein-air landscapes indoors, whereas Brown, for ‘The Pretty Baa Lambs’, forced his second wife Emma to stand in their Stockwell garden in the hot sun with their hatless baby Cathy feigning interest in a model sheep trucked in daily from neighbouring Clapham Common.

Emma’s flushed complexion may betray more than heat and an incipient alcohol problem; there was also the frustration of knowing that Brown’s perfectionism was all that stood between him and commercial success. His friend Rossetti despaired of his ‘excessive elaboration’ of things ‘which are far from beautiful in themselves’, like the potboy’s waistcoat in ‘Work’, but to Brown — who auditioned his extras on the street — the potboy mattered. His roadworks were a minutely detailed excavation of the class stratifications of Victorian society, from the jobless Irish migrants sprawled on the verge to the local MP and his dressy daughter approaching on horseback. ‘Work’ illustrated Carlyle’s philosophy of ‘the perennial nobleness’ of labour and, at the request of a Christian Evangelist patron, included Carlyle himself and a charitable lady distributing temperance tracts. (Brown amused himself by imagining the recipients thinking that ‘ladies might be benefitted by receiving tracts containing navvies’ ideas’.)

During this most creative Hampstead period, Brown was ‘intensely miserable, very hard up and a little mad’. While painting ‘The Last of England’ he was weighing up the alternatives of suicide or emigration to India — he cast himself and Emma, with baby Oliver, as the wretched emigrants. But desperation could not cure his perfectionism. He spent four weeks on the madder ribbon of Emma’s bonnet and heaven knows how long on the marvellously painted grey plaid of her shawl, which has an obsessive realism about it that — like the lilac leaves in the background of ‘Stages of Cruelty’ — reminds me of Lucian Freud at his most sharp-sighted.

A series of crisp little landscapes intended as potboilers turned out to be just as time-consuming as everything else, but the 20 sessions Brown spent in a turnip field in Hendon in 1854 painting ‘Carrying Corn’ still repay the investment. While the Pre-Raphaelite vision now seems irredeemably Victorian, Brown’s truth to nature — thanks to his endless sacrifices in the cause of looking — has stood the test of time. As he himself said: ‘Pictures must be judged first as pictures…I should be much inclined to doubt the genuineness of that artist’s ideas who never painted from mere love of the look of things.’

Comments