Freshers’ Week. It sounds so appealing, even to an uneducated counter-jumper like me who finds the word ‘uni’ so repellent that it’s right up there with ‘gusset’ and ‘spasm’. At British universities it mostly means drinking a lot of alcohol – our historical reaction to most situations – which may contribute to outbreaks of what is known as ‘Freshers’ flu’ in the first few weeks of the university term. But getting the lurgy is the least of the troubles bothering the student body nowadays as they head back to university this week. Thousands are going straight from their studies to long-term sickness, according to an alarming headline in the Times: ‘Students are one of the biggest contributors to rising economic inactivity, with deteriorating mental health a key factor’.

The general statistics around long-term unemployment are shocking, as we’re all aware now unless we’ve been sitting around watching daytime TV and mainlining Jammy Dodgers ever since the pandemic. Post-Covid, 700,000 more souls have succumbed to ‘long-term sickness’, bringing the total to 2.8 million and more than doubling the cost of sickness benefits.

Before Mrs Thatcher got into the ring with the unions, Britain was known as ‘the sick man of Europe’. Now that title has returned to us more literally. As is generally the way in this strange world we live in, language means the opposite of what it is. Thus sick-notes are now often called ‘fit notes’ and can be bought online from actual doctors for less than £35 including a ‘consultation’. Not surprisingly, ‘sickness’ is up 27 per cent in the UK since the end of the pandemic – with one in 15 adults now apparently having the ‘long-term’ version – while remaining stable or falling elsewhere in Europe. We’re now twice as sick as Italy, which is mystifying when you consider all those days at the beach they could be enjoying.

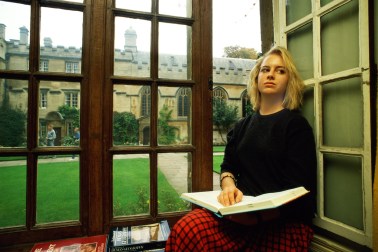

Students seem like scared, soppy overgrown toddlers, with their cancelling and triggering and warnings about books

A detail of particular concern is that we are not just the sick man of Europe once more, but the sick boy – and girl. The fastest growing age group who identify as long-term sick are the 16 to 24-year-olds, an increase of 18 per cent since before Covid. As this group is likely to be physically at the peak of robustness, it’s dismayingly predictable that all too many of them cite Mental Elf issues. It’s odd that thousands of these are university students, going straight from graduation to being out of work. Why?

I can understand working-class kids looking around them at the shattered attempt to create a society where social mobility was the norm, and deciding simply not to bother. The fun jobs, from model to journalist, have been colonised by the dreary spawn of the rich and/or famous. If you are young and were born without ‘prospects’ you are more likely to stay that way than you were back in the twentieth century, a survey by the Institute for Fiscal Studies concluded last year. David Sturrock, an economist at the IFS and an author of the report, said: ‘It may be harder now than at any point in over half a century to move up if you are born in a position of disadvantage.’

It’s also hard to blame youngsters who never bothered to return to education after Covid – the ‘ghost children’ going straight from school to dole. (By the way, the dismal ‘dole’ is a far better word than ‘benefits’, which makes it sound as if being idle is good for a person, when it so obviously isn’t in every way possible.) But university graduates, who have at some point decided to stay at school until the age of 18 – and then commit to another three years of education until they are in their actual twenties? (I had been at work for four years when I celebrated my 21st birthday – and boy, was I ever pleased with myself!) Why are thousands of them giving up before they’ve started?

Maybe the answer lies in how universities have changed. Even though I wanted to get out to work as fast as humanly possible, I could see in the 1970s that there was something sexy about being a student. Yes, they might look dirty and smelly – but they were obviously having it away loads.

Now they seem like scared, soppy overgrown toddlers, with their cancelling and triggering and warnings about books. Once students went to university to have their minds stretched by new ideas, but now too many appear to believe that not being challenged is some kind of human right, that university should be a ‘safe space’. This is higher education as a soft-play area. In the short run, over-sensitive students may feel momentarily better about getting adults to give in to them. But they know in their heart of hearts – that greatest and smallest of unsafe spaces – that hearing different viewpoints without covering one’s ears and saying ‘Na-na-na-can’t-hear-you!’ is a vital part of being a grown-up.

When people are coddled, it makes them more fragile

When people are coddled, it makes them more fragile – and so the vicious circle of mental health and opting out continues. A friend who teaches journalism (of all the careers that you need to be tough for!) tells me that her students are allowed to ‘self-diagnose’ with stress and depression and thus miss lessons, which she must then make up for by tutoring them individually. When did ‘in loco parentis’ come to mean ‘acting like a crazy helicopter parent who believes that their perfectly average child is the centre of the universe’?

Of course we need people who stay in education so that those with a talent or a vocation can become the doctors and teachers we so desperately need to grow as a country. But the fact that so many people with no particular gifts are being over-educated is regressive, not progressive.

I’d be interested to know what the apprenticeship-to-dole (or indeed, the depressed apprentices) stats are. Pretty low, I’d guess. There’s a special satisfaction which comes from doing a useful job, which I get from the eight hours a week I spend steaming clothes in a charity shop. Not to mention that apprenticeships practically guarantee a good income. I knew a posh girl training to be a chef who got sick of being yelled at; she re-qualified as a plumber after a short apprenticeship. Not long afterwards, she brought her week’s cash earnings to my place to measure with a ruler – to amuse me.

The Economist published a cautionary tale last month about behaviour at work which is by no means unusual in today’s graduates:

An older boss was correcting a younger female employee. ‘There is no P in “hamster”,’ said the boss. But ‘that’s how I spell it,’ the 20-something objected. The boss suggested they consult a dictionary. The employee called her mother, put her on speakerphone and tearfully insisted that she tell her boss not to be so mean.

I’ll concede that people like this may be better off staying away from the cut and thrust of the workplace – but why waste all that money on a degree? I’ve never once regretted not continuing in further or higher education. I don’t believe that any institute of learning could have got me further or higher than I got myself, especially considering my extremely humble origins. But reading about the largely self-inflicted sorrow of the school-to-dole mob, I’m gladder than ever that I gave wretched ‘uni’ the swerve.

Comments