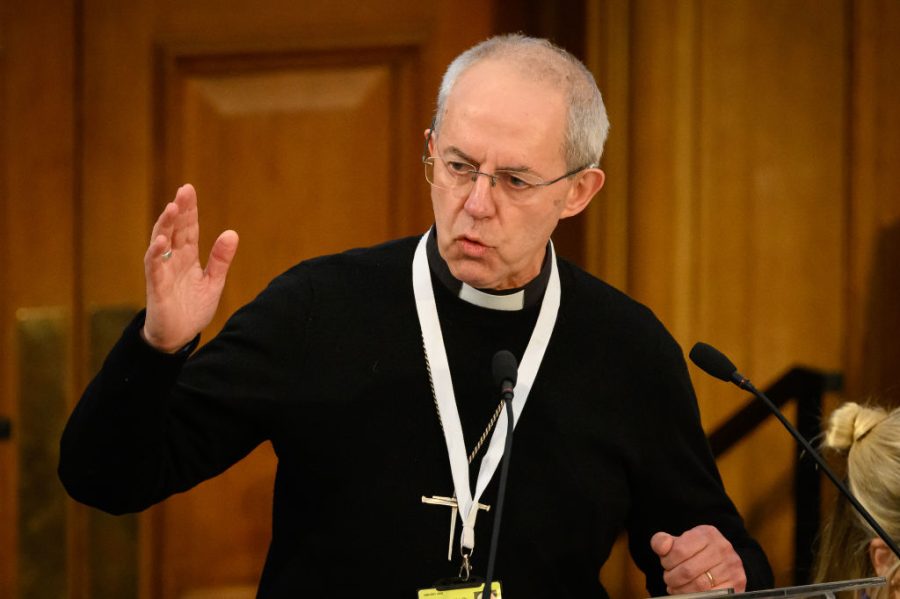

Last week, Justin Welby, Archbishop of Canterbury since 2013, started leading the Church of England. He got off the fence on homosexuality and backed a major change to the Church’s teaching. He said that that ‘all sexual activity should be within a committed relationship, whether it’s straight or gay’. This obviously goes against the Church’s existing official teaching, that sex should not occur outside of heterosexual marriage. The Church is now likely to change that teaching fairly swiftly – probably next year. I predict that Synod will affirm equal marriage within three years.

This shift comes after about 25 years of painful paralysis. At the close of the last century it was already clear to most bishops that reform was needed, that the Church’s condemnation of homosexuality was an embarrassment.

The debate should be framed like this: should the Church affirm monogamous homosexual unions?

So why the slowness? Most liberals point to the deep-rooted homophobia of one section of the Church, and the influence of the Africa-heavy Anglican Communion. Sure. But I think that much of the blame lies with liberals: they failed to make the case for reform, preferring political correctness to honest theological reflection. Unless this failure is addressed, this reform could still misfire. For there is still a large middle ground that needs to be persuaded.

The liberals allowed the debate to be framed in the following terms: should homosexuality be fully affirmed? It’s the wrong question. Step back and consider that question again. In fact, let’s replace ‘homosexuality’ with ‘heterosexuality’. Is heterosexuality something that should be fully affirmed? Surely no one except Andrew Tate thinks so.

The Church has never affirmed heterosexuality per se. It has affirmed heterosexuality constrained by marriage – heterosexuality tamed. In a way this is too obvious to be noticeable. But we have to notice it and reflect on it, or the debate about homosexuality will be misframed.

So the debate ought to be framed like this: should the Church affirm monogamous homosexual unions? Well, that is pretty much what the debate is about, you may say. But ‘pretty much’ isn’t enough. Clarity is needed. And there must also be clarity on the Church’s view of homosexuality more widely. If the Church is to affirm monogamous homosexual unions, this carries an implication – and they had better be spelled out. The implication is that the physical expression of homosexuality outside of such unions is not condoned.

In other words, the debate has been half-baked all along, because liberal Anglicans have shied away from discussing sexual morality in relation to homosexuality.

To understand this failure, we have to take a step back. When homosexuality began to be seriously discussed by Anglicans in the 1960s, it was taken for granted that it was at odds with the Church’s teaching on sex and marriage. Homosexuals were beyond the pale, outside the realm of morality. Gradually this became a more positive stance: because homosexuals cannot marry, we can’t impose the mainstream ethos on them, so let them go their way, let them have a sort of exemption from the general rule, let them work out their own sexual salvation.

I want to suggest that this – the assumption that homosexuals should be treated as a different category of Christian when it came to sexual morality – was pretty disastrous.

It enabled the emergence of a gay Anglican subculture that echoed the attitude of secular gay culture: because we are excluded from the realm of sexual morality, let us proudly embrace that otherness. In some ways, gay Christians went further than their secular peers in trumpeting their otherness. The idea arose that gay Christians have a special sort of authenticity, through embodying a few major Christian themes: they suffer persecution; they defy the ‘law’, in favour of the inner meaning of the gospel (love); they reject shame, and affirm the goodness of bodily creation, incarnation. It’s powerful stuff!

On the other hand, a few gay Christians saw the danger of this separatism and called for a shift to monogamy. One writer of the 1990s stands out: a clever gay vicar called Jeffrey John. His influential book of 1993, Permanent, Faithful, Stable, made the very point that Welby has now come round to 31 years later: fidelity, and the intention of permanence, is the essence of an authentic sexual relationship, gay or straight. He was clear that a gay culture change was needed:

We need to counter the idea that promiscuous gay sex is somehow more excusable than promiscuous heterosexual sex, or that it is a morally irrelevant expression of biological need.

But in fact the book wasn’t all that influential. The Anglican debate continued to be framed in terms of the secular gay rights agenda: homosexuality deserves to be fully affirmed. It ignored Jeffrey John’s point: that for Christians to affirm homosexuality means including it in the dominant narrative of sexual morality, including judgement on the morally lax side of gay culture – the spurning of monogamy. This warning was drowned out by gay Anglicans demanding the unconditional affirmation of homosexuality, as part of God’s good creation.

But surely some aspects of God’s good creation must be affirmed discriminatingly. To call for the affirmation of homosexuality per se overlooks the fallenness of all sexuality. It is an understandable reaction to the vilification of homosexuality, to want to affirm the innocence of this form of sexuality, but it must be contested.

In a sense it did not help that attitudes in wider society shifted and equal marriage came along, for now liberal Anglicans just insisted that it was obvious that the Church should catch up with secular culture as a matter of simple justice. But the secular liberal affirmation of homosexuality is really just a matter of toleration. It is two-dimensional compared to the question of whether the Church should affirm it. For example: does one believe that a Tory MP voting for equal marriage in 2013 would be equally happy if his own son or daughter was homosexual?

Some will feel that I am caricaturing gay Anglican subculture as permissive, as proud of its otherness, as claiming the right to reject monogamous fidelity. So it’s important to give an example.

In Fathomless Riches, Or How I Went From Pop to Pulpit (2014), Richard Coles recounts his youthful involvement in a gay subculture where promiscuity was the norm. Then, when his pop career crashes to earth, he finds God and studies theology with a view to getting ordained.

The reader presumes that his days of casual sex are over. But in fact, after a celibate phase, he has a less celibate one. He relates ‘some months of sexual adventure, and occasionally misadventure’, which might not seem like good Christian behaviour, but it allowed him to come to a fuller understanding of the goodness of God’s creation, and to overcome his sense of shame and isolation: ‘I shared intimacies of the most profound and tender kind with people I would only have passed by in any other place or at any other time…’ The implication is that gay people might have a special calling to dissent from bourgeois sexual norms, and that there is Christian value in this dissent; it can be a means of grace. There is a benign anarchism in casual gay sex, a holy rocking of the bourgeois boat.

My point is that this sort of rhetoric must be called out, or it perpetuates the old assumptions, alienates moderates, stymies reform. The Church could have changed its teaching on homosexuality about 20 years ago if it had defied the politically correct insistence that homosexuality must be affirmed tout court, if it had dared to make a pretty basic theological point: that this form of sexuality is fallen too.

Comments