One day in Berlin, I saw the rerun of the RA’s Young British Artists exhibition at the Hamburger Bahnhof, Berlin’s equivalent of Tate Modern. After that, I saw a superb retrospective of Lyonel Feininger at the Neue Deutsche Galerie. In the evening, I ran into the onlie begetter of the YBA show (which, with the exception of Ron Mueck’s amazing sculptures, had not given me much pleasure), my (unrelated) namesake Norman. I had no wish to discuss Norman’s pride and joy, the YBA, so turned the conversation to Feininger and asked whether Norman had seen it. ‘Ah,’ said Norman, ‘what a bore; I won’t waste my time on him.’

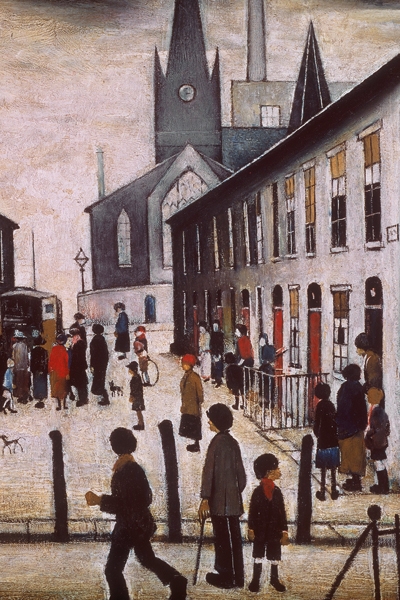

After that I directed a few verbal punches at the YBA, ending with the view that the bulk of them would be forgotten in 50 years. ‘Rubbish,’ said Norman. ‘You might as well champion that old fraud Lowry.’ At which point I seriously thought of directing a few real punches at the RA’s exhibition supremo, but decided that, while having some of Norman’s blood on the walls of the relatively louche ICA might be a good thing, splashing the stuff around the august and bling-laden surroundings of the Deutsche Oper might be an assault too far. So I contented myself with: ‘Just wait and see. I promise you that in 50 years’ time, Lowry will have eclipsed all the YBAs.’

Why, you may well wonder, had I turned myself into a parfit gentil knight on Lowry’s behalf. He was, after all, long dead and loved or respected by relatively few people anywhere and by hardly any in the art world. I can, of course, instantly recognise the major fault of his huge popularity, which is not helped by the Lowry museum in Salford with its plethora (perhaps excessive) of merchandise: posters, reproductions, calendars, coffee mugs, pencils, wallets and many other carefully invented money-spinners. Such a propaganda machine and such popularity are not the English way. It means that Lowry is too clever by half. But of course none of this is true. It’s all of a piece with those music critics who dismiss Puccini while raving about Hans Werner Henze. I’ve even heard Beethoven’s Fifth sneered at by an eminent critic on the grounds that it is performed far too often and over-enjoyed by the plebs.

So can one disapprove of someone merely because he is popular? Clearly one can. I owe my own passion for Lowry’s work to location, location, location, to borrow from the estate agents’ lucrative bon mot. I spent my childhood in Manchester, Stockport, Salford and the other towns that constitute Greater Manchester, clocking up countless miles on my bicycle. I cannot claim to have had anything other than the odd museum excursion — we were seriously restricted by wartime conditions — but I did soak up the topography, the industrial landscape, the slum tenements, the lucky children who had shoes and the unlucky ones who either had clogs or went barefoot. I will do anything legal to avoid the word Lowryland and its concomitant expression ‘matchstick men’, which always makes me sympathise with Goebbels reaching for his pistol whenever he heard the word ‘culture’.

My knowledge of Lowry grew only when I was an adult and a publisher of art books, and I have often wondered whether my love of the artist is simply due to the innate and instant sympathy for what and how he painted; that he reminded me of my childhood is too obvious.

Yet once I had met Lowry, the relationship became human and personal. I was taken on an unsolicited Sunday afternoon to visit him. He was rather put out by the arrival of a fellow denizen of Mottram in Longdendale with me in tow. The atmosphere was as chilly as the winter climate and I tried to make Lowry happy by admiring the art on display. He fought back by asking me to identify what I purported to admire. I named an overpowering Rossetti and even, by sheer luck, because he was the only clock-maker I had heard of, established that the long-case clock was a Tompion. The tale of its purchase from a junk shop in Rochdale acted as ice-breaker and he offered us access to ‘the back room’, i.e., his studio.

I managed to buy a superb small oil painting of some street children for all the money I had on me. That was in 1960, by coincidence the year I began to publish my writings on art.

There followed two radio programmes on the Third Programme. One was a straightforward interview, which had the highest audience rating for the month in which it was broadcast. The other was a symposium in which I interviewed him at length again and extracted golden opinions on and explanations of his work from Herbert Read, John Rothenstein, E.H. Gombrich, Edwin Mullins, Joseph Herman and Michael Ayrton. The Ayrton contribution gave me much pleasure, partly forits acuity and partly because his appreciative perceptions on that occasion made up for the hostile review he had given Lowry while he was the art critic of this journal.

I had also, from 1960 onwards, written frequently about Lowry and after a few years I trained myself to check up with the Tate — which had been immensely helpful in letting me study, on two lengthy visits to its store in Southwark, its magnificent holdings of Lowry paintings and drawings — as to whether there were any Lowrys on view. The answer was always a nil return except for one day when, after much fiddling with the computer, I was told that there was one major Lowry on view — but it was in Tate Liverpool. Thus even this great museum was treating him as a ‘regional’ artist. After my book, L.S. Lowry: The Art and the Artist, was published in 2010, my local bookseller said, ‘It should do very well up north.’

So I would complain fairly regularly about Tate Britain’s many years of neglect and could come to only one conclusion. British 20th- and 21st-century art was in the tight grip of my namesake at the RA and Nicholas Serota at the Tate.

Given that any major Lowry retrospective would be a certain high earner, the lack of one could mean only that Messrs Norman Rosenthal and Serota shared the fashionable dislike of Lowry’s art. Given that what is now Tate Britain is the ultimate repository of British Art, Lowry’s absence on its walls is almost unforgivable. I say almost because my most recent phone call elicited the information that in the rehang there is one Lowry painting now on permanent display.

Also, finally, Tate Britain has overcome its distaste, possibly mindful that the last and only posthumous Lowry retrospective was at the Royal Academy, immediately after the artist’s death in 1976. It was, at that time, the most successful show ever at the RA. In the latest issue of the RA Magazine the Tate exhibition is given a faintly odd plug, which points out that it consists of ‘just 90 of his industrial landscapes. Curated by the Marxist art historians T. J. Clark and Anne Wagner, it examines Lowry’s importance as a chronicler of working-class life.’

As the exhibition will be reviewed, in a future issue of The Spectator, by Andrew Lambirth, I shall restrict myself to rejoicing that at last there is to be a retrospective in a great national museum; not to mention joyfully raising an eyebrow at the idea of Lowry being curated by ‘Marxist art historians’. How wonderful it would be if Lowry could be resurrected so that we could hear his outraged chortle at the word ‘Marxist’. Lowry scorned all politicians whatever their party allegiances, declined both Labour and Conservative knighthoods and utterly loathed the Inland Revenue and all its, to him, unjust and undeserved depredations. He scorned membership of any party but he indubitably leaned to the right, not the left.

Comments