The man who walked up the stairs was the embodiment of the cartoon image of a paedophile. Grey, thinning hair, a couple of days’ stubble and a gabardine raincoat. He had come to persuade us that the age of consent for sexual activity should be reduced to four years old ‘because that’s when children have the ability to express themselves’.

The group managed to fool many liberals into thinking free love for children was the logical next step

The ‘us’ was the small collective who worked for Release, a charity that helped young people who had got in trouble with the law, usually over drug use. This was 1976, a time when liberation was in the air and social mores had changed more rapidly in the past two decades than in the previous two centuries.

The man in the mac represented PIE, the somewhat friendly-sounding acronym which stood for Paedophile Information Exchange. PIE had been using Release’s address at No. 1 Elgin Avenue in Maida Vale as its poste restante – ‘c/o Release’ gave PIE respectability.

Every couple of days an old bloke would pop in and pick up the letters. As a new worker, I questioned the longer-term members of the collective about this arrangement, which had existed for some time, and they agreed to invite a member of PIE to explain its aims. They certainly found it a bit of a shock to discover that the man from PIE even considered four as possibly a bit limiting, as surely babies were also entitled to sexual experience, though he recognised that this might just be his view.

PIE was given its marching orders, which was rather fortunate since a few weeks later the Sunday People did a big exposé and that would certainly have put Release’s Home Office grant at risk. As a brilliant radio documentary series presented by Alex Renton and starting this week shows, this was by no means an isolated incident. PIE’s use of Release’s address was part of a far wider attempt to put across a message that despite its far-reaching and radical nature was considered an acceptable point of view.

Moreover, it would be wrong to dismiss this as merely a bit of overreach by the liberation movements that ended in the 1970s, since another radical notion, the idea that people can self-ID as a different gender, without transitioning, therefore threatening single-sex spaces, has become widely accepted in the past decade, having been put forward by a small group of activists.

Renton’s series follows the progress in the 1970s of PIE and how the group managed to fool many liberals into thinking free love for children was the logical next step after the success of other liberation movements. In particular, if it was OK to be gay, it was fine to be a paedophile. PIE targeted organisations such as the Campaign for Homosexual Equality (CHE), which was seeking to lower the age of consent to 16, in line with heterosexual sex. Prominent PIE activists spoke at CHE meetings to press their case and the programme describes how, at one annual general meeting, a PIE speaker turned up with a prepubescent boy to cheers from the audience but to the horror of some.

Steve Power, who became the chairman of a young gays self-help organisation at the time, told Renton how PIE activists in the 1970s had targeted groups such as his. ‘I felt quite vulnerable around adults and it was important for us to have a clear line about not having adults in the group,’ he said. Others were not so wary and, invited back to the older men’s homes, became victims of sexual abuse.

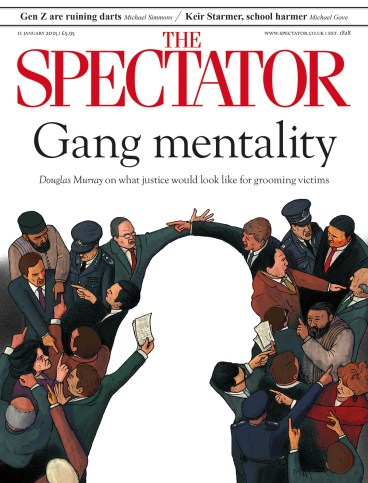

But it was on the political level that PIE’s efforts were most insidious. The extent to which PIE succeeded in infiltrating well-meaning campaigning organisations associated with the opening up of society was remarkable.

The National Council of Civil Liberties (the NCCL – now Liberty) was its most ambitious target, and it managed to become an affiliated organisation and to get a motion passed at its AGM in 1983 condemning ‘attacks on those who have discussed or attempted to discuss paedophilia’.

What was astonishing was the openness of PIE’s campaigning. PIE members, including its chairman Tom O’Carroll, sat on the NCCL’s gay rights committee in the late 1970s and managed to persuade the organisation to lobby against tightening up laws on ‘indecent’ images of children, an argument PIE made in a pamphlet for MPs at the same time.

In Renton’s programme, the journalist Francis Wheen recalls a telephone conversation he had at the time with O’Carroll. Wheen describes how O’Carroll was delighted that a journalist was taking an interest in the issue, and proceeded to explain the campaign’s aims: ‘We’ve got these quite reasonable demands. All we are asking for is a liberalisation of the law, the age of consent law, and we want to lower it to four. It’s just a technical issue.’

Take a legitimate claim and push it to the extreme, clearly crossing basic societal red lines in the process

Such statements were backed up by well-written pamphlets on how children were oppressed by parents unwilling to allow them to express their sexuality, and PIE’s spokesmen made numerous unchallenged media appearances. One prominent founding member, Peter Righton, a well-regarded social work academic, even advised Virginia Bottomley when she was health secretary on the safety of children in residential care. Righton, convicted of child abuse images distribution in 1992, was under police investigation for assaults when he died in 2007.

PIE presented itself as a respectable campaigning organisation, but it was anything but. Many of its members were active child abusers. Renton was sent a list of 316 PIE members, and of the 143 his team have managed to track down, around half have been sentenced, cautioned or charged (several died while being investigated) for abuse offences. As Renton explains: ‘Righton and his network from PIE membership, including already convicted child sexual abuse offenders, managed to infiltrate a range of charities designed to help vulnerable and homeless gay youth. They also succeeded in muddying the waters in liberal rights groups, the media, and thus in social work policy around this issue.’

There are certain parallels with the trans rights campaigns of the past decade in that perfectly legitimate demands have been extended well beyond what most people would accept. The model is the same. Take a legitimate claim and push it to the extreme, clearly crossing basic societal red lines in the process.

The paedophile campaigners camped in on a legitimate fight by gay activists to lower the age of consent. PIE couched its language in libertarian terms about children’s right to sexual expression. They co-opted eminent psychologists to support their case. Similarly, today, the demands of trans people for recognition of their status and action to counter discrimination are obviously perfectly reasonable. However, the idea that ‘trans rights’ then become the right of men who have not undergone any surgery or drug treatment to call themselves ‘women’ and assume that they have the right to enter women-only spaces is not legitimate. Yet anyone even suggesting that or simply calling for a debate on the issue immediately faces accusations of transphobia.

That fear has led to puberty blockers being distributed widely to children seeking help with gender dysphoria without any evidence that such drugs are helpful and plenty to suggest they may cause permanent harm. As Helen Joyce sets out in her book Trans: Gender Identity and the New Battle for Women’s Rights, trans activists are a very small group of people who have managed to take over a wider movement through a false premise. As she explains: ‘What campaigners mean by “trans rights” is gender self-identification: that trans people be treated in every circumstance as members of the sex they identify with, rather than the sex they actually are.’ She points out that: ‘This is not a human right at all. It is a demand that everyone else lose their rights to single-sex spaces, services and activities.’

Sadly, the trans activists have succeeded by persuading many key players of the rightness of their cause. Liberals have ended up being taken in by a radical and exclusive message dressed up as a liberating one. PIE eventually lost the argument because it was so patently absurd. Yet the argument of the trans activist ultras is more subtle and the rapidity with which they have closed down debate through accusations of transphobia have prevented a reasoned debate. Fortunately, with the detailed arguments set out in the Cass Review, the tide is beginning to turn, though not before a lot of harm has been done.

In Dark Corners is broadcast on Wednesdays at 9.30 a.m. on BBC Radio 4 and available on BBC Sounds. Christian Wolmar’s Forgotten Children was published by Vision Paperbacks.

Comments