‘Praggnanandhaa rallied to win the playoff’ is what I wrote last week, as though there were nothing more to say. That came after a humdinger of a final round at the Tata Steel Masters in Wijk aan Zee, in which ‘Pragg’ and world champion Gukesh Dommaraju both lost their final games but nevertheless shared first place with 8.5/13. That magnificent tragedy would have been a fitting conclusion to the tournament, but the modern way is to favour a playoff which determines a single winner. Fans want blood and sponsors want gold, so the thinking goes.

A few weeks ago, Magnus Carlsen and Ian Nepomniachtchi were widely pilloried when they agreed (with the organiser’s blessing) to split the title at the World Blitz Championship. The critics had a point, of course, and playing a few more blitz games is evidently a fitting way to determine the winner of a blitz tournament.

But the situation in Wijk aan Zee is different. The tournament upholds the tradition of classical chess, in which each day’s play is measured in hours and the slow burn of the tournament lasts for more than a fortnight. Settling the whole thing over a couple of blitz games makes about as much sense as playing rock-paper-scissors.

Of course, even silliness can be exciting. Four years ago, I wrote that the blitz playoff at the end of Tata Steel Masters, in which Jorden Van Foreest defeated Anish Giri, was ‘as riveting as it was vulgar’. But this year’s playoff struck me as more of a turn-off.

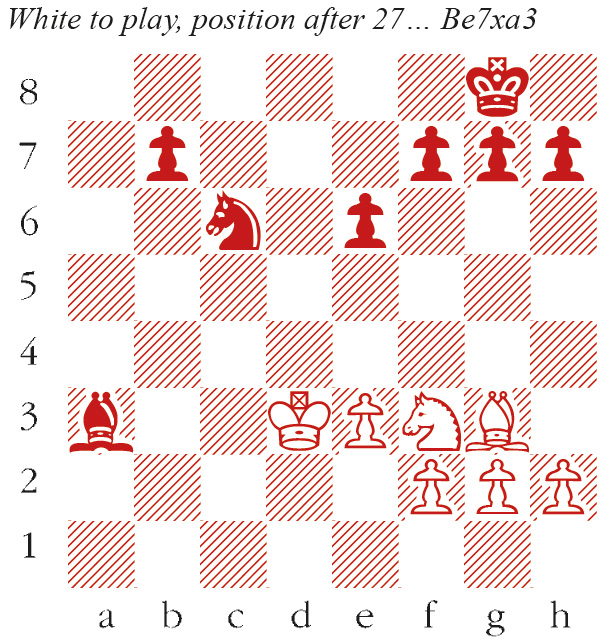

The first blitz game was well contested, until Praggnanandhaa’s clock ran down to his final second and the game was decided by a bad blunder. (See the puzzle below.) He got revenge in the second, a decent strategical game, but Gukesh offered little resistance. From there it was on to sudden death games, in which Black had time odds (three minutes against 2.5 minutes, with a two-second increment at each move), but a win for either side would be decisive. The position they reached after 27 moves is shown in this diagram.

R. Praggnanandhaa–G. Dommaraju

Tata Steel Masters, Wijk aan Zee 2025

With a clean extra pawn, a loss for Gukesh looked inconceivable. Ten moves later his extra pawn was gone, but the endgame was dead equal. Fifteen moves after that, with both players under ten seconds, he fluffed it and lost. I mean no insult to the players, who must have been exhausted, but this was awful to watch, and anticlimactic at that. I’ve played better games of chess while sitting on a bus.

The German grandmaster Dr Robert Hübner died in January at the age of 76. He was a brilliant polyglot and academic papyrologist, as well as a meticulous analyst of chess games, and I remember the pleasure of discussing a game we played 20 years ago. At his peak in 1980, he ranked third in the world. In 1983, he suffered the disappointment of losing a match to Vasily Smyslov in the quarter-final of the Candidates’ matches for the world championship. The match itself was tied, but in that context it was essential to determine who would progress to the next stage of the knockout. The winner was decided by a spin of the roulette wheel, and Hübner lost. It was monstrously arbitrary, but when I see tiebreaks play out as they did in Wijk aan Zee, I wonder – is this really what we want instead?

Comments