Alice Loxton has narrated this article for you to listen to.

On 27 January 1688, Mary Hobry, a French midwife living in London, strangled a man to death. The corpse lay in her bed for several days before she carved it up. Then, in the dead of night, she used her petticoat to drag the dismembered body through the neighbourhood – Castle Street, Drury Lane, Parker’s Lane – to be disposed of. The torso was dumped on a rubbish heap; the legs, arms and head were tossed in a cesspit. What did Mary think, I wonder, as she tiptoed home, finally rid of her husband?

The secret was not to last long. Within hours the evidence was uncovered, sending the West End into scandalised uproar. When the head was found, covered in excrement, it caused a ‘great noise’ to erupt in the streets. Piece by piece the body parts were reassembled and displayed at the Coach and Horses tavern, where they attracted ‘above thousands of spectators’. With the victim identified, Mary’s dastardly deed was exposed. On 3 March she was hanged at Leicester Fields (now Leicester Square) and her body was burned (‘consumed… to ashes’ within half an hour), the crackle of flames accompanied by the cries of the baying crowd.

But was Mary a villain or victim? Her heinous crime was the last resort in a desperate situation. She was trapped in a marriage in which her husband, Denis, inflicted every kind of cruelty – all (though considered shameful) within the law. This was a man who would crush his wife so ‘that blood started out of her mouth’, and bite chunks from her body. Having tried all means of escape – fleeing home, living in hiding, forcing her husband to sign an oath of good conduct before a priest and petitioning for a formal separation – Mary faced a terrible choice: be killed or kill the brute herself.

This tragic, complex tale is one of eight which Blessin Adams untangles in Thou Savage Woman. A police officer turned historian, she is well placed to lead this investigation. Her book, based on research in court archives and framed within a pacy narrative, is a vivid account of women’s lives and society’s perceptions of them in early modern Britain, warts and all.

We learn of the brutality of the London seamstress Leticia Wigington, who instructed that a 13-year-old girl apprentice in her charge be whipped until her blood flowed ‘like rain’. Not satisfied with such cruelty, she salted the wounds ‘to render their tortures more grievous’, only for the girl to faint and die three days later. Leticia was hanged at Tyburn on 9 September 1681.Then there is Phillipa Cary, a servant girl from Plymouth, who fatally poisoned her spiteful employer in 1675. While waiting to be hanged, she was forced to watch her accomplice’s body burn: for two hours, the wind ‘drove the smoke’ of the immolated corpse ‘full in her face’.

Certain forms of criminality, such as witchcraft, were perceived as uniquely feminine. Unexplained deaths would be attributed to the spells and potions of ‘haggs’ – daughters of the devil who had sold their souls in exchange for otherworldly powers. Poisoning was seen as being easily veiled by a woman’s customary domestic duties such as mixing medicines, herbal remedies and cordials. Ratsbane (the common name for arsenic) was a cheap and regular household item used to kill rats. When ingested, its symptoms of abdominal pain, vomiting, bloody diarrhoea and thirst were indistinguishable from those of common ailments at the time.

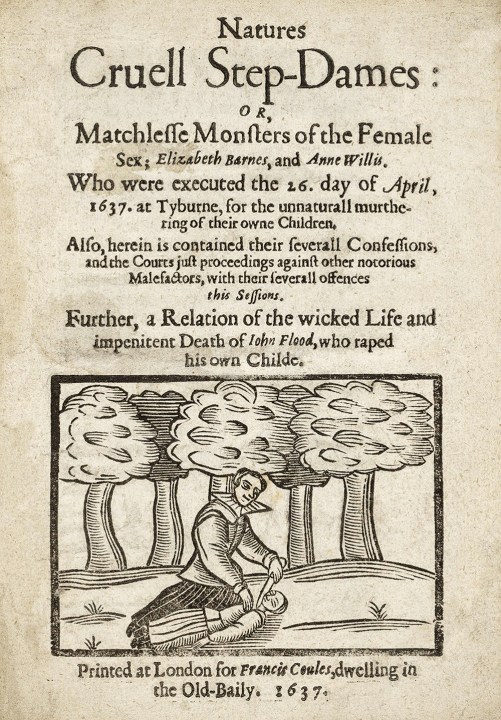

Some women killed because they had to; some because they wanted to; some were innocent scapegoats. But every case triggered a media frenzy. While male violence was considered normal, even honourable, female violence was perceived as deviant and strange, and excited a morbid fascination. In the ‘wonder news’ which emerged, female killers were presented as monstrous freaks, defying all contemporary understanding of woman’s nature. Here was a society which was at once repulsed by and attracted to murderous female rebellion. It is an obsession which, Adams argues, remains to this day, with tabloids branding women murderers as ‘she-devils’, ‘evil monsters’ and ‘unnatural’ mothers.

There is, perhaps, an elephant in the room. Adams offers a critique of sensationalist true-crime accounts. Yet here are eight of the most ‘extraordinary and rare’ murder cases which ‘thrilled and terrified ordinary men and women’ and produced ‘narratives of murderous women’ which were ‘guaranteed to sell’. Is Thou Savage Woman part and parcel of the genre it seeks to decry?

Nonetheless, the result is a fascinating read. Adams navigates the evidence with the calm clarity of a detective and an eye for titillating detail. Cutting through centuries of embellishment from pamphlets and tracts, she presents her subjects as far from vulnerable or passive but equal to men in their capacity for violence and cruelty. Paraphrasing the historian Frances Dolan, Adams notes that ‘a feminist view of history need not be a hunt for victims’.

This is popular history at its best, where the past is brought vividly, albeit gruesomely, to life, and we come a step closer to making sense of that most elusive of things: the strange contours of our ancestors’ minds.

Comments