Matthew Parris

From the late Alan Lomberg, my English teacher at my school in Swaziland, in my school report: ‘I’m sure I have only slightly less high an opinion of Matthew’s literary abilities than he has himself.’

Sebastian Shakespeare

The late Alan Clark once described me in his diaries as a ‘tricky little prick’, but he was beaten to the punch decades before by a teacher who dubbed me a ‘giant prick’. To this day I’m not sure which is the greater compliment or insult.

Quentin Letts

The word that appeared in my school reports time and again was ‘facetious’. Facetious is a fine word, not least because it presents all five vowels in alphabetical order, but would a teacher nowadays dare use it of a pupil? I was an annoying child. A junior matron took one glance at me and slapped me, saying: ‘It’s little Letts, always smirking.’ I hadn’t done anything wrong, but she whacked me and I banged into the medicine cupboard door, cutting my eye. Still have the scar. But I didn’t really mind.

Craig Brown

The most memorable insult I ever received – memorable in the sense that it still haunts me – came from a sympathetic teacher at my prep school called Mr Buxton. Towards the end of a school debate about something or other, I plucked up the courage to stand and make a point. Heaven knows what I said. All I remember nearly 60 years on are his words to everyone else: ‘Give the poor chap a chance.’

Jonathan Miller

My life changed as a fifth-former at Bedales after getting back what I’d thought to have been an especially perspicacious and entertaining history essay. ‘THIS IS JOURNALESE!!!’ scrawled my teacher, Ruth Whiting, in her signature green ink. She certainly meant it to be an insult. I took it as career advice and have never looked back.

Roger Lewis

At my South Wales comprehensive, insults and personal remarks from the teachers flew thick and fast. It was meant to be character-forming. Fatty, Twiggy, Sticko, Pizza Face, Gravel Guts, Scabby Legs, Speccy Four-Eyes and Twp, a Welsh word meaning dim – perhaps derived from une taupe, French for mole. Owing to John Hurt as Quentin Crisp in The Naked Civil Servant, the effeminate (anyone who didn’t worship rugby) were called the Quentins. ‘You are worse than a Quentin,’ I was told. ‘You are quaint!’ Why is it always the games masters who perfected this sort of bullying? Decades later, I am so pleased if news reaches me of their death by cancer.

Matt Ridley

On arriving at Eton in 1970, I was sent to be tried out for the choir. A teacher played a chord on the piano and asked me to ‘sing the middle note’. Being tone deaf, I had no idea what to do. I tried ‘la’. He accused me of deliberately trying to avoid joining the choir.

Stephen Fry

‘An intellectual grasshopper’ is one that I remember from my German master. I don’t know whether I earned the epithet or what it even means, to be honest. Another was: ‘If he were truly as clever as he thinks he is, he would be the teacher and I would have the pleasure of ignoring him as he ignores me.’ Ouch.

Griff Rhys Jones

‘If brains were dynamite, you wouldn’t have enough to part your hair.’ My masters didn’t generally insult us, they just whacked us. We learned basic grammar – subject and object – by Dickensian process. ‘The master hits the boy,’ intoned our first-form Latin teacher, directing a stubby finger at his own red face and clumping each infant he passed. We loved it. We were ‘poodle fakers’. ‘Lazy tykes’. ‘Doomed’. Our backcombed barnets were ‘lank tresses’. Our zip-up Chelsea bootees ‘grossly illegal footwear’. We were ‘slackers’. ‘Dreamers’. ‘Dim’. Nothing was accidental. ‘Sorry your concussion has ruled you out of rugby. Are you still concussed or just naturally ignorant?’ Real abuse was reserved for reports. My headmaster specialised in withering scorn. ‘He thinks his charm is enough. I doubt it.’ ‘What happened to that charm then?’ a friend asked recently.

Bruce Anderson

I had just arrived at Campbell College and was labouring through my first gym period. The master in charge watched my efforts with a sardonic appraisal: ‘Did your previous school have a gymnasium?’ But the greatest insult I heard from a teacher had nothing to do with me. These days, it might have led to trouble. At a prep-school cricket match, one small boy could not land a delivery on the wicket. At the change of overs, the master from the other school addressed the incompetent: ‘What’s your name, boy? ‘Badcock, sir.’ ‘Your balls are worse.’

Catriona Olding

Kraftwerk-loving Stuart Mulholland started it. He called me ‘Swan Vestas’ because I was tall, thin and had red hair. In those days you could buy a cigarette and a match for 2p from the van parked outside the school gates. One morning my English homework jotter came flapping across the classroom and hit me on the head. Inside were the words: ‘Swan Vestas, you can do better. Take a leaf out of Boxer’s book and tell yourself, “I must work harder.”’

Richard Madeley

The worst insult a teacher ever threw at me was also the bitchiest. I was best friends with a boy this man clearly had a massive crush on. It was a classroom joke. One day my friend was injured on the rugby field. I was helping him off when the teacher ran over.

‘Why is Madeley helping you?’

‘He’s my best mate, sir.’

‘Madeley? Your best friend? You can do much better than him. I’ll help you. Madeley, go pick up the orange peels.’ Nice guy.

James Delingpole

My teachers never had to invent any insults for me because my surname did the job for them. If you yell ‘Delingpole’ in the right tone of voice – angry, appalled, disbelieving, or whatever you feel the particular moment requires – at a small, impertinent boy, it squishes him more than adequately.

Rory Sutherland

I regret to say I’ve chosen an easy target: it was always games masters who were the most horrible. There is a strangely Darwinian streak to games masters. If a pupil is not academically or artistically gifted, most teachers will at least persevere and do their best. But sports teachers are genetic determinists to a man: from the first millisecond they discern you have no athletic or sporting talent, they would treat you as a complete blot on the landscape and were happy to abuse you for the merriment of everyone else. In the 1980s, ‘poof’ and (for some reason) ‘ponce-eared poof’ were standard terms to describe anyone who disliked organised games. So when one particularly nasty games master’s son was flashed by a paedophile, most of us nerdy types saw it as karma in action, the natural justice of the universe reasserting itself.

Martin Vander Weyer

I have no recollection of being insulted by any of my schoolteachers. But at Worcester College, Oxford, at my last appearance before tutors and the Provost for a verbal final report after three fun-packed and occasionally riotous years, my economics tutor described me as ‘the sort of undergraduate who was supposed to have been abolished by the 1944 Education Act’. To which the Provost, the great and good Lord (Oliver) Franks, endeared himself to me for ever by responding: ‘Not at all, Martin is a valuable member of our community who has clearly enjoyed his time here, and we wish him well.’

Rachel Johnson

When I was at the European School in Brussels, all the English children were in the same class at the beginning, in the early 1970s. I was taught aged seven with my older brother, whom our teacher, Mr Black, considered gifted – but me not so much. For homework one day we were told to write ‘an exciting story’. I did my best but when my English book came back, Mr Black had written, ‘Oh how very boring Rachel’ at the end in thick red felt-tip pen. I still try to bear that in mind whenever I write a sentence.

Harry Mount

Bob Bairamian (1935-2018) taught classics at my prep school, North Bridge House, by Regent’s Park. His insults were jokes really. To punish me for getting a Greek verb wrong, he cried: ‘Put drawing pins on the juniors’ chairs!’ When he smashed his head in a car crash, he devised a new punishment: ‘Mons Minor [my nickname], come to the front and pick the scabs off my forehead.’ I adored him.

Melissa Kite

My maths teachers were baffled by me, and struggled to express how hard it was to teach me anything. I had one who used to call me Esmeralda, which everyone found very amusing. Another one used to bang his big ruler against the blackboard at some algebra or geometry he couldn’t get me to solve and scream: ‘Are you stupid? Why can’t you see?’ I wish I could have answered: ‘Because I can’t do maths and I never will be able to so I’d give up if I were you…’

Philip Hensher

I still admire my English teacher who boldly gave the class The Waste Land. At 16, I was a mad Wagnerian. We got to the lines Eliot quotes from Tristan. I thought it would be iconoclastic to remark: ‘Of course, Isolde dies in the end of an orgasm.’ Mr Buckley’s timing was concise and impeccable. ‘Inconvenient,’ he said with a flick of a glance. As a put-down of weary experience, as if he had heard every conceivable teenage attempt to shock, it had the quality of making me feel he’d got my number.

Sean Thomas

My cruellest nickname came from a history teacher I liked, who innocently noted that my surname came from the Welsh/Cornish: ‘As’ = son, of Tom. Gleefully my schoolmates seized on this, and I very nearly became ‘Ass’ – and ‘Asshole’ – for ever, a fate I avoided by urgently thinking up nastier, more diverting names for everyone else. Thus are writers born.

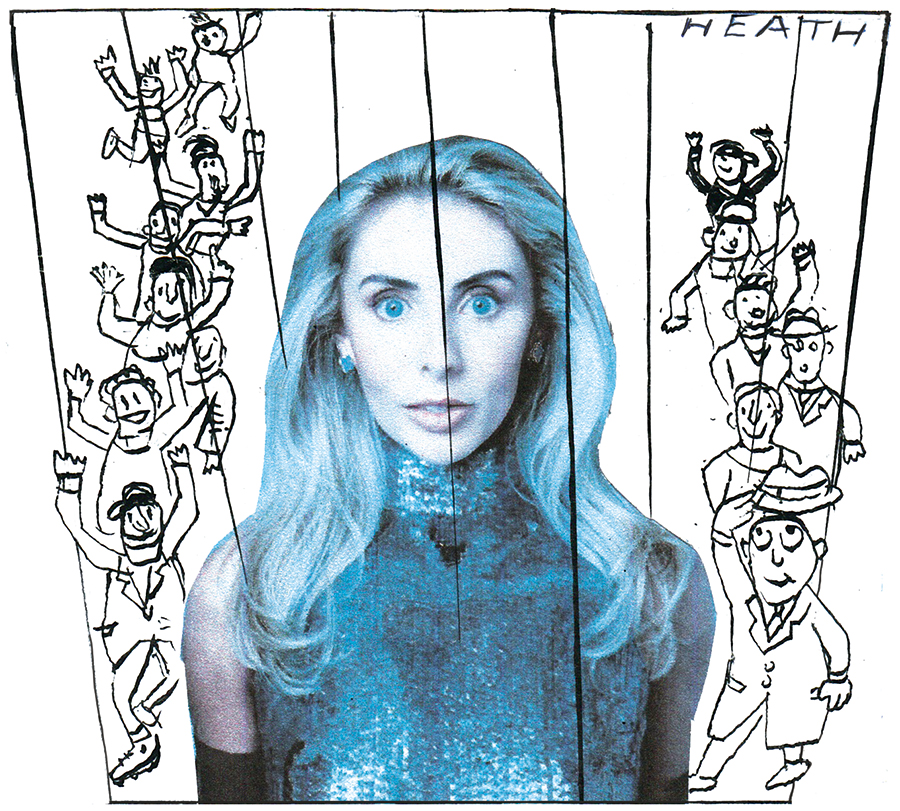

Petronella Wyatt

My maths teacher and I were standing in a classroom at St Paul’s Girls’ School, which I attended back in the 1980s. I had just failed my maths O-level. ‘Petronella,’ he said, ‘you cannot get through life on charm alone.’ As I began to purr, he added: ‘Incidentally, that was an insult.’

Julie Burchill

One of them told me that I would probably ‘end up’ as the editor of Private Eye. I was only 15 and I didn’t even know what Private Eye was. I still don’t know if it was praise or a diss.

Comments