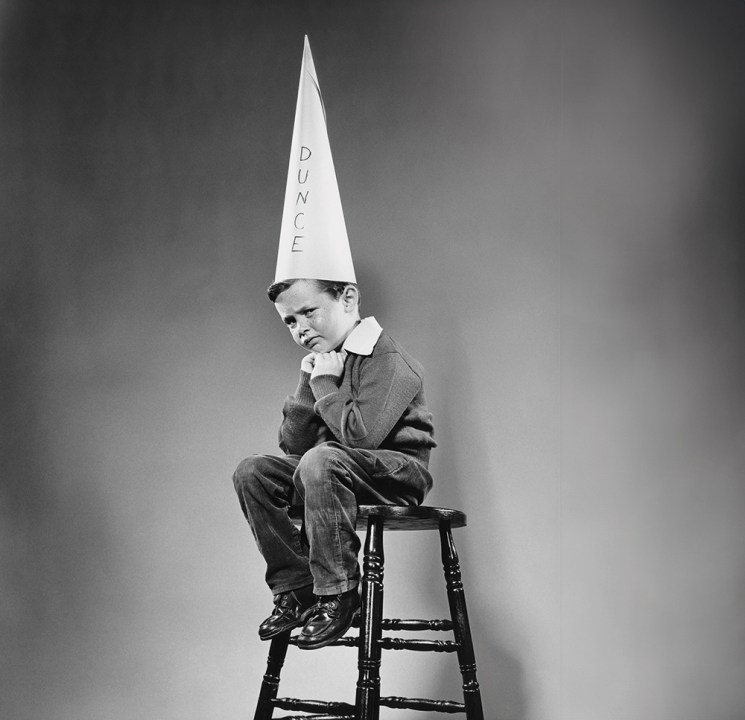

On top of the canings and endless gym-shoe whackings – those ‘short, sharp shock’ corporal punishments endured by prep-school children (especially boys) until the late 1970s – what were the most memorable punishments inflicted on pupils born from the 1930s onwards?

To put today’s more humane prep-school punishments in perspective (they’re not even called punishments but ‘sanctions’), I asked people in their seventies and above which punishments they most remembered. ‘The Denzil Blip,’ said Julian Campbell, who was at The Hall School in London in the 1950s. ‘Denzil Packard had been a prisoner of war of the Japanese and had a mangled finger. Offending boys were clipped on the head, with this finger being the point of contact.’ There was also ‘the Rozzy Haircut’. This was given by Mr Rotherham, ‘who would take hold of your hair with his hand and pull your head down to grovel on the floor’.

Another described simple verbal terror. ‘The classics master had been in the Navy during the war. When presented with an incorrect translation, he would shout, “Balls, bollocks, bang my arse, frog’s bum and monkeydust”.’ Others mentioned ‘being made to learn the Benedictus by heart’, ‘running round the playing field’, and ‘detention every night, no Sunday exeat, and no sweets when the tuck shop opened’.

By the time I was at a girls’ boarding prep school in the 1970s, the punishment for frolicking after lights-out was to sit in silence facing a wall in semi-darkness for an hour, or to be made to make your bed again and again until it felt as if your arms would fall off. For boys, non-corporal punishments included writing 100 lines, such as ‘I must not fritter away my expensive education.’

The ultimate fear was that your parents would be told about your bad behaviour and there’d be hell to pay at home. Nowadays, parents all too often side with their child against the school. This is the kind of parental interference that makes being a teacher increasingly hard. As the sought-after private tutor and former prep-school master Ed Clarke said to me: ‘These days, invoking discipline in the classroom can create a rod for your own back, because the child tells their parents, the parents contact the deputy head, and you get called in for a bollocking.’ A more confident school stands up to parents.

The pervasive atmosphere of fear and shame recalled with a shudder by many seems to have vanished from today’s prep-schools. Punishments are now restorative more than punitive. The entire philosophy of the relationship between pupils and staff has changed. The theory that good behaviour is best learned through fear has been ditched. Now children are instilled with the mantra ‘be kind’ and ‘respect others’. And that goes for both pupils and staff.

‘Very, very few children are innately unpleasant, but they’re human beings and they will make misjudgments’

‘Very, very few children are innately unpleasant,’ said Matt Jenkinson, headmaster of New College School, ‘but they’re human beings and they will make misjudgments. They’re learning to live alongside people who might irritate them. What we try to do is to forestall errors of judgment, talking to them about kindness and co-existence.’

When pupils do fall short, what all three schools said to me is that there needs to be transparency in how misbehaviour is dealt with. At New College School, there’s a ‘graduated system of sanctions’: a white referral form, a green referral form, and then (the most drastic) an orange referral form, involving a talk with the headmaster. ‘The hope,’ says Jenkinson, ‘is that you never need to get to the point of exclusion, which is nuclear.’ Recently the school has introduced the new first stage, the white slip before the green slip, which denotes: ‘We’re not angry, but if this carries on, it would escalate.’

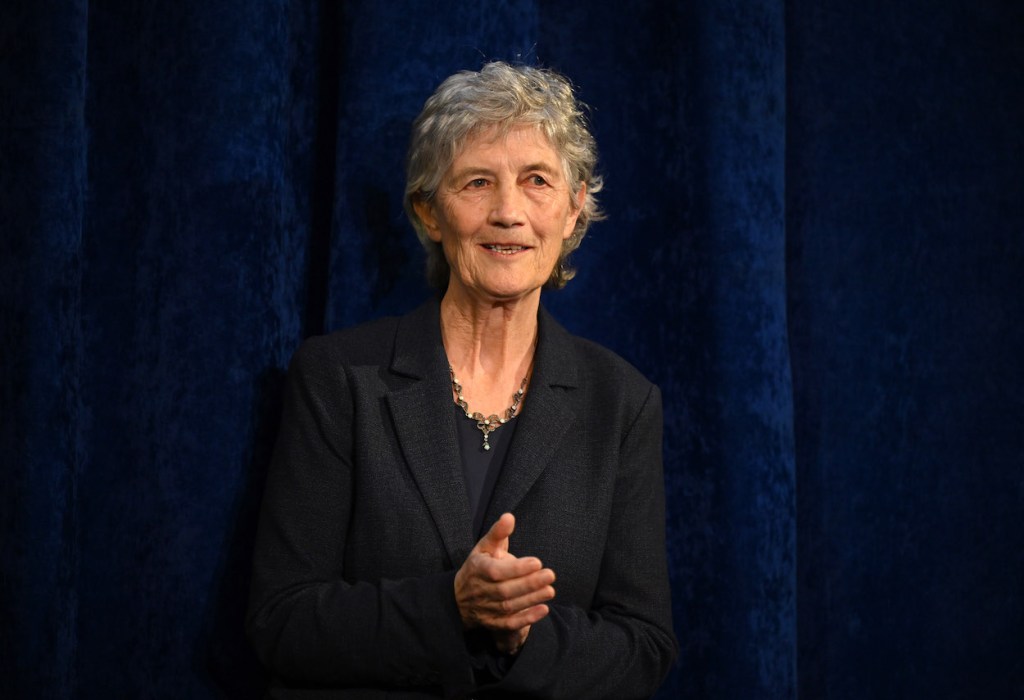

Hilary Phillips, head of the girls’ prep school Hanford, says: ‘It’s not so much we’re imposing discipline – we’re teaching the girls self-discipline. If a girl has misbehaved, I’ll make sure I find her when she’s with the guinea pigs or the ponies, or sitting in a tree with her book, and I’ll say, “Do you understand why that wasn’t a great course of action?”’

If the girls misbehave, ‘We’ll start with a gentle warning, then there’ll be a second warning, and then a punishment, starting with a conversation: “You’ve chosen to do this three times, which shows you don’t care. Your action is going to create a reaction.”’ Then follows an ‘SYR’ (‘Serves you right’): a tedious task tailored towards the misdemeanour, such as cleaning out the minibus, or wiping muddy cross-country trainers.

‘We welcome mistakes – we’re a prep school,’ says Kath Harvey, deputy head of pastoral and safeguarding at the Dragon Prep. ‘What we aim to instil in the children is intrinsic motivation: a moral compass which tells them “This is the right thing to do.”’ To deal with mistakes, the school has a tiered system to promote awareness of behaviour. ‘We start with a “there-and-then reflection” at the end of the lesson, escalating to a meeting with the head of year, and then to a meeting with the senior leadership, if needed. “Talk me through your decision-making,” the children are asked, requiring them to reflect upon what went wrong and how they’d do things differently next time.’

In the boarding houses for 200 full boarders and 100 flexi-boarders, there’s a relaxed, homely atmosphere. But ‘consistent poor decision-making will result in a loss of privileges, such as not being allowed to go into town, or loss of tuck, so children learn there are consequences for unconsidered actions’.

With these humane and non-humiliating methods, and pupils being treated as mature, thinking beings from a young age, the next generation is being prepared for adulthood. But they won’t be able to entertain their grandchildren with stories of the ‘Denzil Blip’ or the ‘Rozzy Haircut’.

Comments