There’s a lot to digest in the new Crime and Justice Commission report, which came out today. Its proposals include, for example, a legal ban on access to social media for under-16s and a universal digital ID card system. But the most eye-catching idea in the Times-sponsored report is that for those outside the most serious crimes – notably murder, manslaughter, rape and serious violent and sexual offences – the right to jury trial should go. Instead, other crimes for which currently there is a right to a jury should, if the defendant chooses, instead be tried by a so-called intermediate court consisting of a judge sitting with two magistrates.

There is little doubt that the government would agree. Labour is desperate to do something about the backlog in the crown courts (which is scandalous: some defendants are already being told that there are no free slots before 2028). It also knows full well that a choice of jury trial materially increases the chance of acquittal and would welcome a chance to appear tough on law and order. Indeed, when the government commissioned a review of the criminal justice system from ex-court of appeal judge Sir Brian Leveson last December, it pointedly put forward something similar to the Times proposal as one option.

In one situation there remains a fairly powerful case for keeping the status quo

Perhaps predictably, the Law Society and the Bar Council are opposed on principle, and have instead called for an end to government penny-pinching on the justice system. Interestingly enough, though, there is a good deal to be said in favour of the reformers’ views.

For one thing, it would almost certainly save valuable court time. While it may be over-sanguine to suggest that a change from a jury to a judge sitting with a couple of magistrates could reduce trials from days to hours, it would simplify proceedings and reduce organisational problems, and that can only be a good thing.

Secondly, outside really serious crimes, where there is an arguable constitutional need to keep the state in check by making it convince twelve of the defendant’s peers that the defendant is indeed the heinous monster it says he is, it’s not immediately apparent why a jury should be seen as some kind of constitutional shibboleth. In most cases of, say, middle-ranking theft or criminal damage, or proceedings arising from late-night punch-ups, its function is essentially to find the facts: is witness X’s recollection sound, or did the defendant intend to walk out with those two bottles of tequila without paying for them? Is a jury so much more likely to bring the necessary measure of common sense and everyday experience to such things than a judge and a pair of magistrates? One rather doubts it.

There is also a further point. Jury trial for middle-ranking crimes doesn’t only allow defendants to game the system on the basis that they have a better chance of acquittal on the facts. As has happened on occasion in the last few years, in politically polarised cases it may also allow defendants to defeat prosecutions on less deserving grounds. Take, for instance, the case of demonstrators accused of criminal damage. Even if the judge gives a plain direction that there is no defence in law, they can still suggest, and sometimes obtain, an acquittal on the basis of sympathy for the cause being supported. The effective preservation of public order in such cases by making them triable by judge and two magistrates, who are less likely to be so influenced, is a considerable good.

Two cheers, at least, in favour then. Why only two, you might ask? In one situation there remains a fairly powerful case for keeping the status quo. Take the case of a person on trial for publishing material alleged to be racially or religiously inflammatory, or of a householder charged, possibly by an over-zealous crown prosecution service, with using unreasonable force against a thief. In such a case the issue is likely to be about whether the material was sufficiently inflammatory, or the force used unreasonable, which concerns not so much fact as judgment and appreciation of the socially acceptable. On a matter like this there is a strong argument that ordinary members of the public may well be better placed to decide than judges or even magistrates. In cases like this, if the court is satisfied that there is a plausible defence on these lines, we clearly ought to allow the defendant to opt for full jury trial.

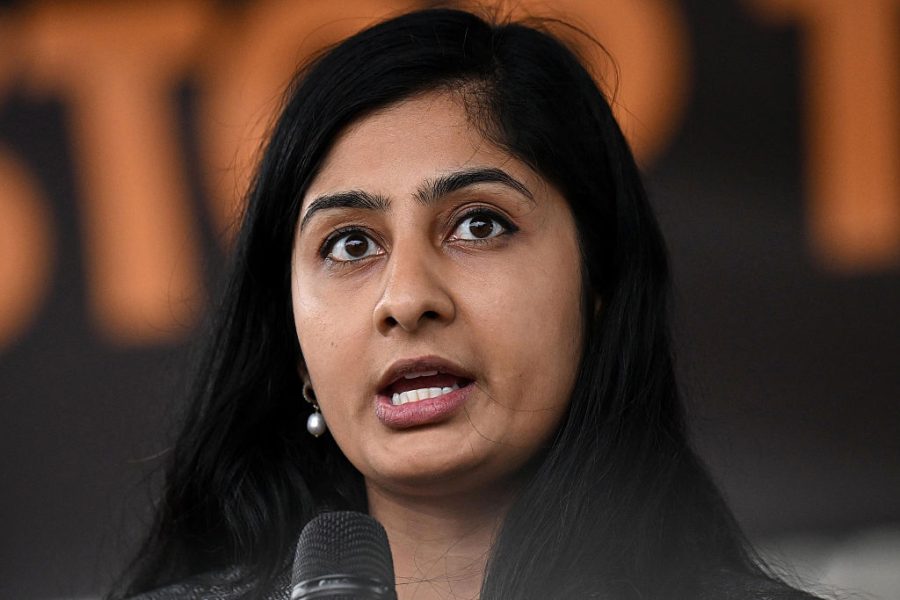

The Times’s report is more a ballon d’essai than anything formal, despite its contributors including a former Lord Chief Justice and a retired director of public prosecutions. For any indication of the government’s official view, we shall have to wait for Leveson to report. Nevertheless, ballons d’essai have their uses: if no one shoots them down, they may well show which way the wind is blowing. The betting must be on a nod of approval from Shabana Mahmood if Leveson comes down on the same side as the authors of this report. And if there is, for once, perhaps she ought to get her way.

Comments