It’s quite something when the Chinese Ministry of Defence is more transparent than its British equivalent. Despite the Prime Minister on assuming office promising ‘transparency in everything we do’, a flying visit to Beijing last Wednesday by the UK chief of defence staff, Admiral Sir Tony Radakin, only emerged via a Times scoop a day later.

Official silence from an habitually opaque UK MoD about the first such visit for 10 years ceded the information advantage to China, allowing it to paint a rosy, false picture that Radakin had discussed deepening engagement and cooperation with his Chinese equivalent, General Liu Zhenli. This in turn prompted outrage from UK China hawks who accused Radakin of engaging in ‘a ghastly game of appeasement’ prompted by a Labour government hellbent on ‘kowtowing to China’. In the information void, commentators fulminated about the dodgy timing amid a deepening US-China trade war and Chinese military exercises near Taiwan, Radakin’s naivety, US disapproval, and oddly the well-known and manageable security risks of entering the Chinese MoD.

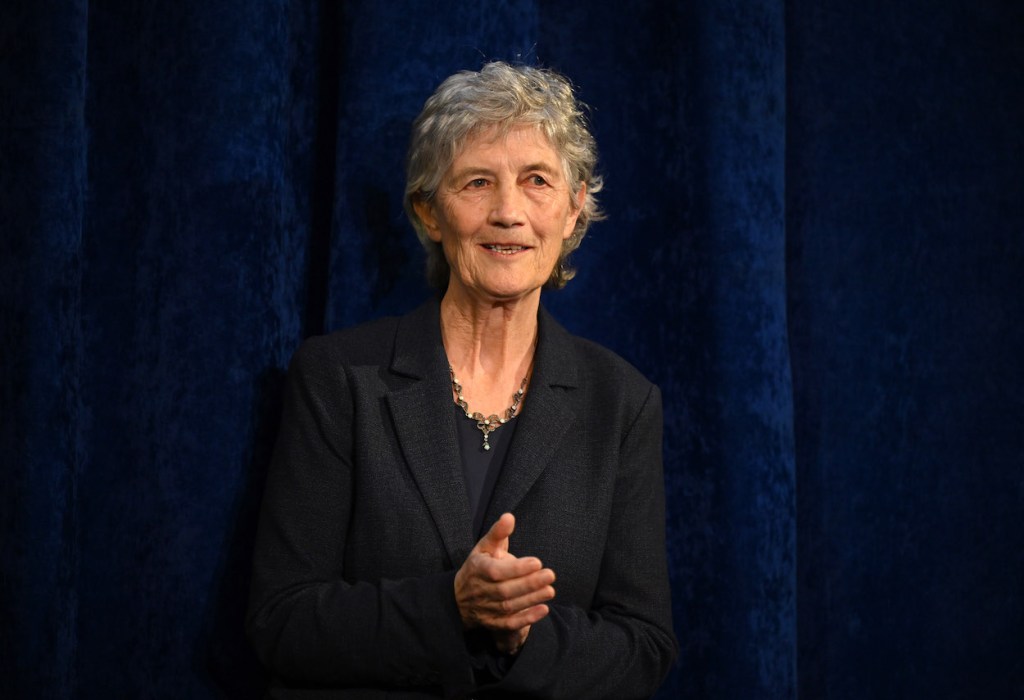

This is all overblown. Military to military communications matter. Radakin’s visit to Beijing was timely, clear-eyed and long overdue. He’s no naif, as I saw first hand in Moscow just before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. And there’s plenty on the agenda. I’m told that Washington was well aware of Radakin’s visit, and that the Americans had their own staff talks with the Chinese a week or so beforehand.

China presents us with a formidable strategic problem. UK policy says that China represents an ‘epoch defining and systemic challenge’. Starmer’s government uses the policy mantra of ‘cooperate where we can, compete where we need to, and challenge where we must’, consistent with its predecessor while also leaning into a long-term national ’tilt to the Indo-Pacific’ first set out in 2021. The forthcoming National Security Strategy is unlikely to change this assessment or national direction of travel.

Radakin has noted in the past that the UK’s small, permanent military presence in the Indo-Pacific provides the foundation ‘for [our] strategic relationships, like Aukus [a trilateral security partnership between Australia, the United Kingdom, and the United States] and GCAP [a 6th generation stealth combat aircraft with Japan and Italy], which will endure for 50 to 75 years.’ He could have added crucial relationships with India, Republic of Korea and a security pact between Australia, Malaysia, New Zealand, Singapore, and the UK. China’s coercive behaviour, military modernisation and growing assertiveness pose a challenge to all of these.

Managing the systemic Chinese challenge will remain essential for the UK national interest. Dialogue to understand China’s military thinking while explaining our own supports both mutual understanding and also strategic and regional stability. Direct, hard-headed and frank engagement allows for transparency about each other’s ambitions, national interests, and military developments. In times of tension, it also provides the means to manage escalation. Its absence risks misinterpreting each other, leading to miscalculation.

It will take time to get past the usual Chinese vitriol and make any defence dialogue functional

Critics argue such high-level visits are too conciliatory to a state guilty of human rights abuses and aggressive territorial claims. They worry that engaging China undermines the UK’s moral authority. MoD lack of transparency also fuels scepticism about its real purpose. But seeking to understand a potential adversary is not to defend how they behave. Moreover, dialogue is intrinsically connected with and can contribute to deterrence; we engaged with the USSR throughout the Cold War. That is not to say it is always successful as we know from our relationship with Russia.

Restoration of senior Sino-UK military communications after a decade should be welcomed, not slammed. Yet this reboot is likely to have been fraught, with mutual trust low and suspicion high. As an academic pointed out to me, it will take time to get past the usual Chinese vitriol and make any defence dialogue functional.

In a post on X, Radakin only said that he had discussed ‘a range of security issues’ with General Zhenli. Meaty issues could have included the UK’s Indo-Pacific tilt, nuclear stability, plus regional security issues such as Japan, Chinese encroachment in the South China Sea, Taiwan and the situation on the Korean peninsula, including the use of North Korean troops by Russia. Radakin will have sought assurances that the capture of two Chinese nationals in Ukraine does not presage direct Chinese People’s Liberation Army involvement in Russia’s abhorrent war. He will have probed the nature of Chinese defence industrial support to Russia’s war machine.

Speaking at the Chinese National Defence University, as Radakin reportedly did [although oddly we haven’t seen the speech], allowed him to set out the UK position directly to future Chinese military leaders. In turn, China will have raised Aukus and GCAP, having publicly slammed both in the past. Zhenli will have found it difficult to avoid trash talking the actions of both the US and UK, especially concerning Taiwan and naval Freedom of Navigation Operations in the region.

In particular, in the interests of safety, transparency and risk reduction, both sides will have discussed the forthcoming deployment of the UK Carrier Strike Group. This multinational group, led by the Royal Navy’s flagship HMS Prince of Wales, will sail from the UK shortly after Easter to reaffirm ‘the UK’s commitment to the security of the Mediterranean and Indo-Pacific’. In 2021, Chinese state media warned that the group’s predecessor should not ‘tempt fate’ or conduct ‘improper acts’ prior to it entering the South China Sea. Fortunately, all interactions at sea between the Chinese and Royal Navy were deemed safe and professional.

Radakin will want to keep it that way. Meeting jaw to jaw remains better than war.

Comments