The online speed awareness course cost £101, or a few pounds less if you didn’t want to book ‘flexible’ so you could change it if something went wrong, which it was bound to.

Quite how companies like the AA, which deliver these courses, divvy up the spoils with the police I have no idea. I don’t want to know. I just want to be left alone once they’ve all got what they want out of me.

Naturally, when I logged into this course at the appointed time I couldn’t get the camera working on my laptop. Obviously, I had to phone my IT guy and he had to get me to download a program which allowed him to access my laptop remotely.

‘Slide the slider!’ he kept saying. ‘What slider?’ ‘You’ve got your camera covered! They’ll be a slider!’ ‘There’s no slider!’ Calm down!’ shouted the course organiser, whose face I could see in a little window.

Eventually, I found a slider above the lens and slid it. I was in. The course organiser scanned my driving licence and there I sat in a rogues’ gallery with five other wretched souls who had been caught doing speeds of 30 and 40mph, and whose blank faces stared from their little windows like so many convicts in prison. All except one. One chap rather amusingly had his camera trained on the top of his forehead throughout.

This load of mugs and me, we all had one thing in common. We were going slow, but not slow enough. They ought to call it a Slowness Awareness Course.

‘Have any of you ever been involved in an accident?’ asked the course leader, who had a cheerful Brummie accent and kept saying: ‘Ow-kay!’ ‘Anyone been in an accident?’ Silence. ‘No?’ No. ‘Think how you’d feel. Ow-kay? You’d be scared, you’d panic, you’d feel guilty.’

Yes, we would. But we haven’t, so we didn’t and we don’t.

There were lots of simulations showing us how much we were hurting people in all these accidents we weren’t having.

We were shown deep breathing exercises to calm down. These would have been useful if I had been wound up, angry or excited and doing 90mph, but as I had been meandering with uncertainty at 40 on a strange dual carriageway that turned out to be a 30 while visiting my parents in Coventry, taking their car in for its MOT after my father had a stroke, I didn’t really need breathing exercises for my driving, so much as the period after it when my parents and I started getting really terrifying letters from West Midlands Police threatening us with the magistrates’ court and the confiscation of our licences, until eventually the small print of one of these letters revealed that I could do a speed awareness course.

And thankfully, given that I live in Ireland, I could do it online.

Eventually, the course got around to explaining the speed limits on dual carriageways. We were shown a series of animations demonstrating that to be a dual carriageway, it had to have a solid barrier, or raised central reservation, but the catch was that this could be a concrete strip that was only slightly raised.

To wit, the raised bit might be hardly noticeable. This was crucial because if there was a central reservation, it meant you could knock yourself out and do whatever you thought was dual carriageway speed, even if there were street lights, which normally denoted 30.

The cheerful Brummie postulated that if you weren’t sure, and while waiting to see a speed limit sign, it was probably all right to do 40 or more if there was a raised area in the middle of the road.

‘So that’s dual carriageways. Ow-kay! So are we all clear about dual carriageways?’

I put my hand up. ‘I’m sorry,’ I said, ‘but I’m not hanging my hat on a slightly raised bit of concrete that might be a central reservation or might not. I’m going with the street lights rule. I’ll be erring on the side of 30 on the next dual carriageway I go on if – and it’s a big if – I ever drive in the UK again.’

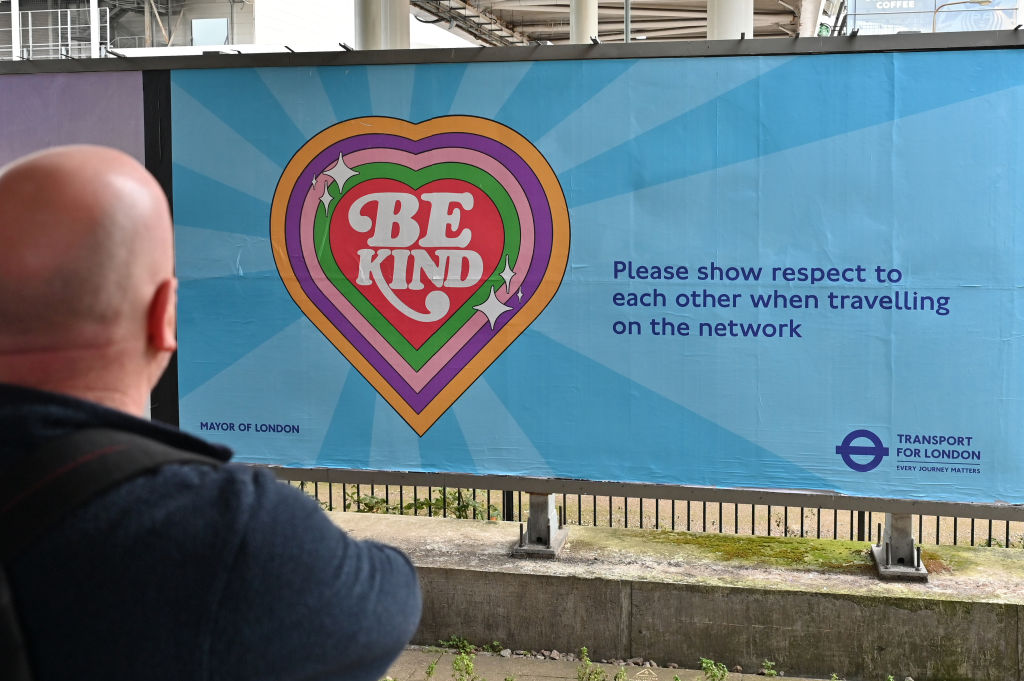

‘Ow-kay! So that’s dual carriageways! Everyone clear?’ And everyone nodded their heads. They knew that they were going back out there to get fined again, whether on a strangely slow dual carriageway or a newly 20-ised zone that had sprung up overnight in the middle of the street they were living in. Resigned, these people were. Sitting ducks. Payers of fines and penalties. The compliant majority. Shoulders hunched, heads down.

Lastly, the cheerful Brummie told us that we would all have to make an action plan to complete the course.

I started scribbling notes as he went round the group asking each person how they intended to keep to the speed limit. When he got to me I read out my notes: ‘Do not visit Britain again, or if you have to, do not drive. Do not take the ferry, do not hire a car if you fly. Use Ubers. Do not drive parents’ car, even in a dire emergency or to do your father a favour when he’s in hospital.’

‘Ow-kay!’ he said, ‘So I hope we’ve all learned something!’

And he ended by informing us that ‘99 out of 100 insurers’ would not ask about speed courses. On which chilling note, having put a whole new world of fear into me about my obviously imminent insurance hike, he brought the course to a close.

Comments