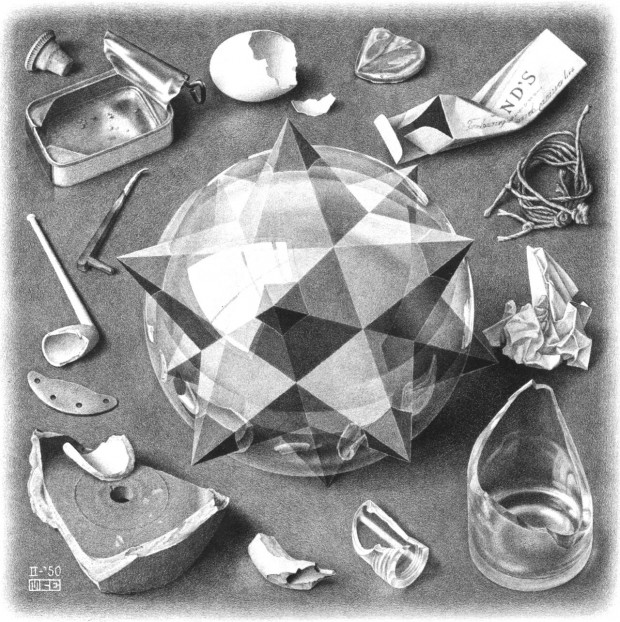

‘Surely,’ mused the Dutch artist M.C. Escher, ‘it is a bit absurd to draw a few lines and then claim: “This is a house.”’ He made a good point. That is what almost all artists since the days of Lascaux have done: put down some splodges of paint or a line or two and proclaimed, ‘This is a bison’, ‘This is a man’, ‘This is Mona Lisa’. One of the aims of Escher’s work, which is currently displayed in an exhibition at Dulwich Picture Gallery, was to undermine such pretensions to represent reality.

At first glance, his images often seem meticulously, even aridly factual. ‘Still Life with Mirror, March 1934’ shows us a bathroom looking-glass on a table, toothbrush and paste arranged in front; but the reflection in the glass is of a medieval Italian street. It takes a moment to realise that this is a Lewis Carroll state of affairs. The looking-glass is a window to a different world; the city cannot be inside this room.

In a work such as this, Escher (1898–1972) had an obvious affinity with his exact contemporary, the Belgian surrealist René Magritte. He, too, was struck by the fact that a picture of a pipe — or a dressing table — was not the thing itself. Technically, and in mood, he also had a good deal in common with Anglo-Saxon wood engravers such as Clare Leighton and Eric Ravilious.

Escher specialised in print media, almost always in black and white, and deployed with extreme precision. Even in his early years, however, his lithographs and woodcuts such as the view of ‘Castrovalva (Abruzzi), February 1930’ had an eerie atmosphere and vertiginously plunging perspectives.

Already you get the feeling that those neat little black shapes might metamorphose into something else. A few years later, they did. ‘Day and Night, February 1938’ is a landscape viewed from the air. On the left, black geese fly over sunlit fields; on the right, there are white birds and the scenery is darkening into night. In the middle, the two flocks intersect, revealing themselves as just flat, geometric shapes — which in turn merge into the pattern of fields below.

A good deal of Escher’s work was to do with this kind of duck/rabbit conundrum. He also delighted in paradoxes such as the building in ‘Ascending and Descending, March 1960’. This is roughly in the style of Brunelleschi, progenitor of Renaissance single-point perspective. But the staircase on its top storey forms an endless, impossible loop around which figures trudge up — or down — forever. Escher was interested in infinity, not just optical illusions.

Some of his work has a cartoony, kitschy quality, which may explain why — despite his popularity with the public — Escher has not been taken seriously by museums (there are hardly any of his prints in British public collections). He was limited and a bit repetitive, but this exhibition demonstrates that he deserves a place in art history. Escher fits neatly, like one of his flat tile-like forms, in the gap between Magritte and Bridget Riley.

Another figure who has yet to find a secure position in that scheme is the late John Hoyland. With the exhibition of his early painting that inaugurates Damien Hirst’s Newport Street Gallery, however, Hoyland (1934–2011) is coming posthumously back to prominence.

He was, as it happens, the first contemporary artist with whose work I came into contact. A benefactor presented my school with one of his canvases, principally featuring a large green rectangle. Presumably no one knew either what to make of this or where to put it, and it ended up hung forlornly in a remote corridor.

This could stand as a metaphor for what happens to artists when the art world can’t think quite where to place them. Hoyland, born in Sheffield, and a creator of abstract paintings on a heroic scale, was — at least in British art — one of a kind.

He began brilliantly but didn’t quite sustain that promise, which is perhaps why this exhibition concentrates mainly on the 1960s. Hoyland’s paintings from that era were made up of squares and lozenges of soft red, orange and green. There was a connection with Rothko, but they do not have the looming, spiritual quality Rothko managed to give his oblong patches of colour.

Hoylands are imposing through the grandeur of their scale, but in a more architectural way. His paintings from 1966, a peak productive year, though clearly ‘abstract’, seem like simple structures in space. They suggest a corollary to that observation by Escher: it’s hard to put down a few rectangles and not have someone say, ‘This looks like a house.’

With the opening of this big, airy and beautifully designed gallery Hirst is following his erstwhile Svengali, Charles Saatchi, in setting himself up as an independent force to the mighty Tate (which ought to mount such reassessments as this, but seldom does). What’s more, Hirst already seems to be succeeding. At the Frieze art fairs early Hoylands were shown on more than one stall and — as they do at Newport Street — looked unexpectedly strong.

Comments