Sir Keir Starmer was alerted in the early hours of Friday by his national security adviser, Jonathan Powell, that Israel’s assault on Iran was ‘under way’. The Prime Minister got a text message while in his flat above No. 11. It was not a bolt from the blue. Downing Street has not said so publicly, but the government was told in advance what was coming.

Publicly, Starmer’s relentless emphasis has been on ‘de-escalation’ of the crisis. Privately, ministers have been expecting an Israeli offensive since December. David Lammy, the Foreign Secretary, led a cross-Whitehall tabletop war-gaming exercise into how events might unfold on Monday last week, four days before the first air strikes.

Pressure to take a tougher line with Israel over its offensive in Gaza is not confined to Labour’s backbenches

The reason for this public reticence is fourfold, involving strategy, espionage, law and politics. There is a genuine concern that the later waves of Israeli strikes, aimed at forcing regime change rather than destroying Iran’s nuclear programme, are directed towards a goal which is both un-obtainable and unknowable. ‘Be careful what you wish for,’ says one security source. ‘There is no guarantee that what would come next would be any better. You might just get a younger, more organised ayatollah.’

The second reason is that one of the British government’s priorities since the crisis began has been to keep the UK’s embassy in Tehran open. This is not because the Foreign Office has developed an uncharacteristically energetic approach to consular care for British nationals in the theocratic state. The embassy is a base for intelligence officers running what (limited) assets the UK has in Iran. ‘It is useful for us and for others who have no embassy there,’ whispers a nodding, winking official. Translation: the CIA wants MI6 to remain in business. ‘Our visibility [of what Iran is up to] is not good,’ one of those involved in crisis management admits. Without a presence on the ground, the confusion would be worse.

Part of the explanation is that the Attorney General, Lord Hermer, is again flexing his muscles. ‘The AG has concerns about the UK playing any role in this except for defending our allies,’ one official who has seen the legal advice explains. Consequently, the armed forces have not joined the efforts to shoot down Iranian missiles fired into Israel in the last week, unlike in October, when the RAF helped defend Israel against an Iranian salvo of 200 missiles. Britain has played a role in protecting Jordan from stray missiles but no more.

The final reason, however, has the most potential to determine the fate of the Starmer government. After a period of globe-trotting in which the Prime Minister was dubbed ‘never-here Keir’, Starmer’s handling of international affairs has generally been seen as a positive, continuing full-throated support for Ukraine, avoiding a run-in with Donald Trump, signing multiple trade deals and even getting US approval for the Chagos Islands deal. Until now, foreign affairs have been a refuge from his domestic travails.

But international events are throwing up problems which threaten to torch the government’s economic plans as well as widen fissures in Labour between the leadership and much of the parliamentary party. In short, foreign affairs are now a danger for Starmer where they were once a distraction or an opportunity.

The conflagration over Iran risks raising inflation and delaying cuts to interest rates. The price of oil has already risen to $76 a barrel. If the mullahs close the Straits of Hormuz, blocking shipments from the Gulf, experts think it will rise above $100 and perhaps as high as $130.

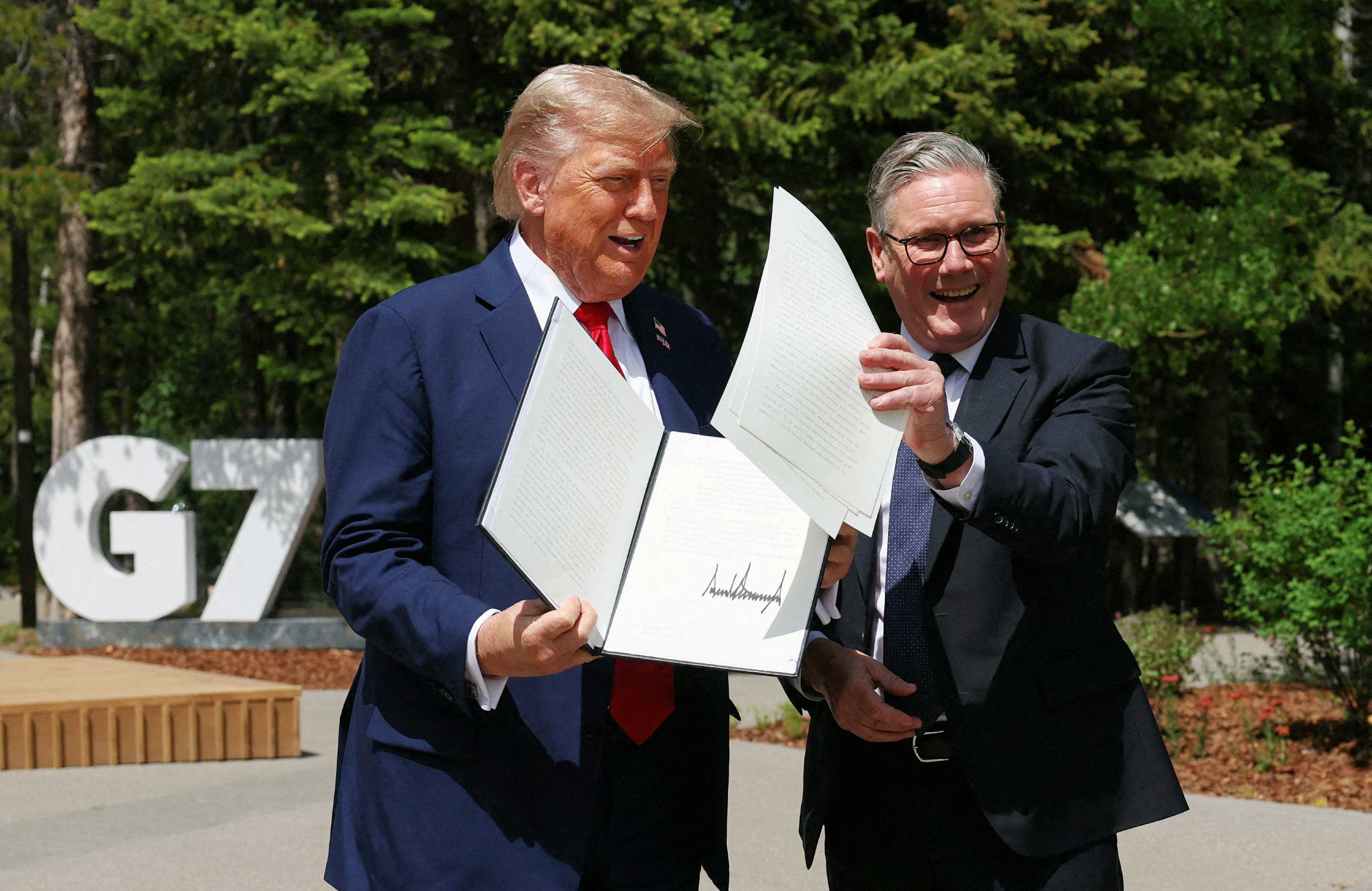

This week, at the G7 summit in Canada, Starmer was delighted to get Trump to sign an executive order enacting the trade deal with the UK which reduces tariffs on cars from 25 per cent to 10 per cent. ‘It is worth £14 billion of exports,’ says one of those involved: ‘It probably saves our car industry.’ The Prime Minister’s first move after Trump signed on the dotted line was to call Adrian Mardell, the chief executive of Jaguar Land Rover, to tell him the good news. But while Scotch whisky exporters are also delighted, Britain’s ethanol industry is warning it will be wiped out – and losers always shout louder than winners.

Problems also loom for the NHS, since Trump regards the health service’s bulk–buying of drugs for far less than US healthcare companies pay as industrial cheating – particularly given that American billions paid for the research. Anything which drives up the cost of medicine could render the 3 per cent NHS budget hike in the spending review irrelevant.

On the political front, Labour’s soft left is no longer willing to tolerate a morally neutral stance on Israel. When the French proposed a conference last week to pave the way for recognition of a Palestinian state, ‘there were strong rumblings for unilateral recognition’, a Labour MP says.

Complicating everything is the presence in the Commons of five independent pro-Gaza MPs and the fear on the Labour benches that that number could be 20 or 30 after the next election. Those whose seats are at risk include high-flyers such as Wes Streeting and Shabana Mahmood. ‘The moral–outrage politics that lie beneath Gaza are more difficult for the party in the medium term than the Iraq war was,’ an MP says. ‘Muslim voters are less loyal to the party. Iraq, at the time, was seen through the prism of government dishonesty, rather than because it was a moral outrage.’

Event

Coffee House Shots Live: Are the Tories toast?

Pressure to take a tougher line with Israel over its offensive in Gaza is not confined to Labour’s backbenches. Hamish Falconer, a former diplomat who is the Middle East minister, ‘has been pushing internally for a while’ says one MP, noting Falconer’s potential interest in the leadership one day. ‘He is trying to position himself in the PLP [Parliamentary Labour party].’

The first move was to sanction two Israeli ministers who publicly backed the ethnic cleansing of Palestinians. Ministers were content with the way the decision landed. The two Israelis, from the hard right, are not popular with British Jews and neither the Board of Deputies nor the Jewish Leadership Council criticised the move. When Starmer spoke to Benjamin Netanyahu after the first air strikes on Iran, the Israeli premier did not even mention it.

Starmer is expected to have to make a decision on whether to join a US-Israeli military effort against Iran

But that direction of travel makes a nuanced position on Israel and Iran more difficult. Senior figures talk about a ‘multi-front regional war’, drawing a distinction between some fronts (Gaza) where ‘Israel needs to be restrained’ and others ‘where Iran has been the aggressor’ and Britain is prepared to see Israel act more freely. When David Lammy gave a statement to the Commons on Monday, he felt the need to point out (primarily to his own side) that Israel views Iran’s nuclear programme as a threat to its existence. ‘There are a lot of new MPs on the Labour benches who don’t know a lot about it,’ observes one party source. An MP describes Lammy’s speech as ‘Janet and John does the Middle East’.

The next flashpoint could be the government’s national security strategy, which will be published early next week, before Starmer heads to Tuesday’s Nato conference in the Hague. Insiders describe it as a ‘hardening and sharpening of our approach to national security’ which will lead to a ‘more un-apologetic and systematic pursuit of national interest’ – a far cry from Lammy’s talk of ‘progressive realism’. Its author, John Bew, who advised Boris Johnson, Liz Truss and Rishi Sunak on foreign affairs, is a Labour man but also the biographer of Castlereagh, the realist’s realist.

The review contains three pillars: ‘security at home’, ‘strength abroad’ and ‘sovereign and asymmetric capabilities’. It links economic prosperity and defence technology to the military and intelligence agencies. The bit that will have some Labour MPs clutching their pearls, however, is an acknowledgment that ‘multilateral cooperation’ and ‘institution building’ – the classic Labour foreign policy formula – ‘will not be enough [in] the current climate’.

A summary circulating in Whitehall reads: ‘We may have to act outside our comfort zone if we are to deter and defend ourselves against threats.’ One of those who has seen the review adds: ‘We’ll have to work with people who we don’t naturally necessarily share values with in pursuit of the national interest and national security.’

The challenge of multilateral cooperation will then be laid bare at Nato, where the secretary-general, Mark Rutte, is pushing for member states to commit to 3.5 per cent of national income for defence and 5 per cent in total on defence-related spending. Rachel Reeves committed Britain to 2.6 per cent by 2027, with no mention of how the UK would get to its stated target of 3 per cent. The only good news for Starmer is that Nato is taking a broader than usual definition of spending. The budgets of MI5, MI6 and GCHQ, as well as support for Ukraine and the cost of maintaining the Diego Garcia air base, can all be thrown into the pot.

Before that, British officials expect Starmer to have to make a major decision on whether to join a US-Israeli military effort against Iran, a decision which could enrage both Trump and Labour MPs. Starmer’s team, like the rest of us, spent Tuesday evening waiting for the President to reveal his plans on social media. Pete Hegseth, the US defence secretary, recently told his British counterpart, John Healey: ‘What he writes on Truth Social, that is the best indication of present thinking.’ On Tuesday, Trump demanded ‘UNCONDITIONAL SURRENDER!’ from Iran, by which the Brits believe he means it giving up its nuclear programme. ‘There is a strong likelihood that we would be asked to contribute [military assets],’ an official says.

‘There are those who would want nothing more than to just bring Iran back to negotiations and de-escalate immediately,’ says one Whitehall figure. ‘And there are those who are thinking this has been a problem for the past 20 years and maybe we should just explore the idea that you could blow up the problem and it might go away.’ Lammy is ‘on the far left of that spectrum’. Lord Mandelson, the British ambassador in Washington who attended a Cobra meeting in London on Tuesday, is nearer the other end.

What of Starmer himself? The same criticisms that have dogged him in his handling of domestic affairs (see the belated U-turn on a grooming inquiry) can now be heard about foreign policy. ‘If anyone can tell me where the Prime Minister is, I would be astonished, because it is not entirely clear,’ grumbles a senior civil servant. The answer is:no longer in his comfort zone.

Comments