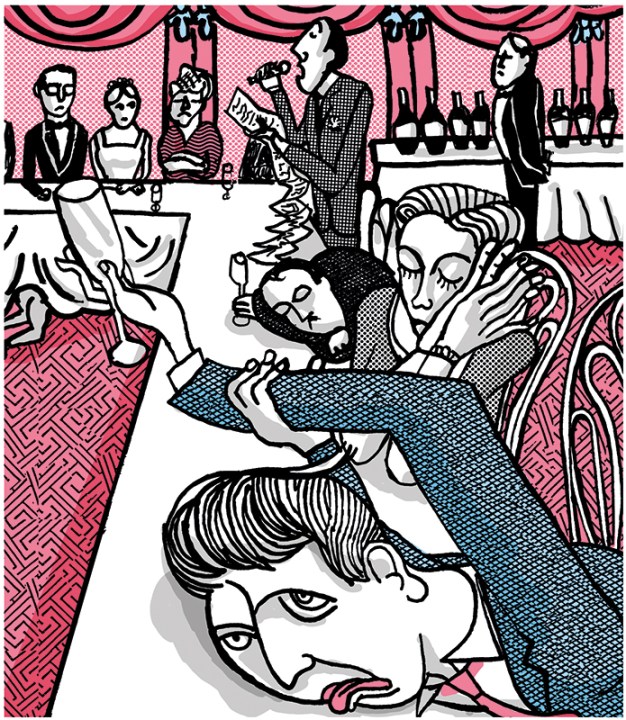

Perhaps the most traumatic part of attending an American wedding – much worse than the bridesmaids coming in the wrong way, the proliferation of dinner suits and the tendency of couples to write their own appalling vows – is the tradition of the ‘rehearsal dinner’. This, an event the night before the wedding, is where the United States of America gets to play out its full psychotic breakdown in the context of a couple’s nuptials.

It seems unfair to expect Home Counties dads to be masters of oratory

Anyone, and I mean, anyone, is allowed to stand up and make a speech. Meaning that Uncle Robert E. Lee IV from Alabama can stand up and compare marriage to the Battle of Antietam while Cousin Xi/Her from Portland, Oregon, can rise to give a polemic on how marriage is a form of oppression, but in this case she’ll let it pass. If only we’d have known that the non-conformist instincts of the pilgrims would come back to bite us in such a horrific way, we’d have sunk the Mayflower before it left Plymouth harbour. I say come back to bite us, because these American customs are now popping up in English weddings with alarming speed. Nowhere is this clearer than in the amount of wedding oration – both before and after dinner.

Indeed, one of the least consequential side-effects of the 1960s revolution has been the inflation of wedding speeches. It feels outdated – sexist, even – to limit the talking to the groom, best man and father of the bride, so now basically everyone gets to have a go: bride, maid of honour, mother of the groom, you name it. Divorce has only added to the potential rollcall. A stepfather may have had far more to do with a bride’s upbringing than a biological father, and therefore requires a speech too.

All very inclusive, but the playbill does start to look fuller and fuller. Suddenly, rather than having two parties demanding to be represented, you might have four, or even eight. Often these come in such quick succession that listeners are denied a moment in between to recharge their glass and at least dull the horror with alcohol.

All this is compounded by the rather awkward fact that many of us simply can’t make speeches. Given that the House of Commons has become a rhetorical dead-zone (e.g. ‘Does my Hon. Friend agree with me that we are moving at pace to deliver on our plan for change?’), it seems unfair to expect that generation of Home Counties dads to be masters of oratory. Rather than spare us the ignominy of having to listen, however, the modern tactic seems to be a policy of safety in numbers, as if five bad speeches are somehow better than one.

For my wedding later this month, we will be only too happy to keep speeches at a minimum. Having gone to town on the church service – full choir, four hymns plus a Te Deum, two scriptural readings and two poems – paring back the after-dinner element seems only fair. The hope is that by that time, most guests will have drunk enough to lose at least two of their five senses.

We have also been mindful that, in the grand scheme of things, having lengthy speeches – beyond a quick toast – is a fairly recent innovation. So much of modern romance owes its philosophical grounding to Jane Austen; yet despite the popular imagination of her as a doyenne of weddings, the novels yield almost no detail about the ceremonies themselves, apart from Mrs Elton’s bitchy little aside about Emma’s pared-back wedding: ‘Very little white satin, very few lace veils. A most pitiful business!’ There are certainly no speeches mentioned.

Perhaps the greatest fictional wedding oratory comes in Four Weddings and a Funeral, where Tom, played by James Fleet, tries to copy his friend Charles’s (Hugh Grant) more successful best man speech from an earlier wedding, but it all goes horribly wrong. In the film it lands badly; I happen to think it’s the single funniest minute of all. ‘When Bernard told me he was getting engaged to Lydia, I congratulated him because all his other girlfriends have been such complete dogs… Although may I say how delighted we are to have so many of them here this evening.’

This is actually an ideal best man speech because, on a day where every moment is plotted out to the second, it brings a joyous touch of anarchy – and when so much wedding time is given over to sentimentality and pleasing untruths about the perfection of the couple, it can offer a welcome moment of relief, and reality. That said, too much Dutch courage can be perilous. A best man slurring his way through five pages of pre-prepared gags and boorish anecdotes about stag-do antics is the only thing worse than the doling out of mawkish praise. So – a plea this wedding season – let’s keep the speeches short, and ideally not too sweet.

Is Maddie right that most wedding toasts are awful? She joins the latest Edition podcast to discuss alongside professional speechwriter Damian Reilly:

Comments