Soaring crime and a growing air of discontent means that few Brits are happy about the state of their nation. There is one man, however, who seems to enjoy this deteriorating country quite a lot: the Ambassador of Japan to the Court of St. James’s, Hiroshi Suzuki.

Paddington’s values have very little to do with what Britishness means in Northern Ireland

Suzuki’s cheery social media posts, in which he extols the virtues of the United Kingdom as seen through the eyes of an ardent Anglophile, are wildly popular. From sharing photographs of himself drinking ale in the Turf Tavern in Oxford, to making an origami daffodil to promote St. David’s Day, the Ambassador seems to be thoroughly happy with life in Britain.

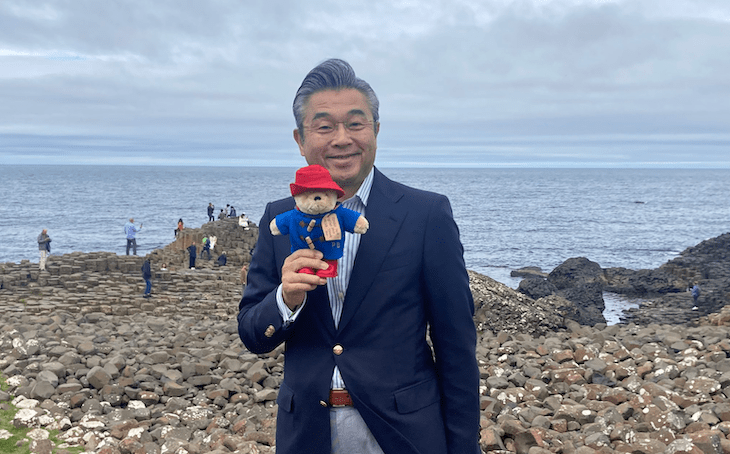

Suzuki has one quirk, however, which would make him an antagonist in World War Twee: everywhere he visits, he brings a little Paddington Bear toy with him. Much has been written in these pages and elsewhere on the cult of Paddington, about how this fictional bear has been co-opted by the great and the good as a symbol of Britain’s values in our pro-globalisation post-historical society. Paddington is kind and unfailingly polite, has a dry, witty humour, respects traditional institutions, and enjoys marmalade sandwiches. He is also an illegal immigrant, arrived in Britain by way of boat, who was recently given a passport by the Home Office. All of this, naturally, makes him appeal greatly to the lanyard class of progressives.

This week, Suzuki visited Northern Ireland, along with Paddington, to carry out his ambassadorial duties and do a little sightseeing. He shared a photograph of the ruins of Dunluce Castle on the northern coast and commented on its ‘beautiful scenery’. Over a quarter of a million people saw his post.

It was not long before the Paddington toy was whipped out for a photograph, and people gushed over the perceived Britishness of it all. However, Paddington’s values – those of a left-wing media class distilled and dumbed down through various layers of appeal-to-children – have very little to do with what Britishness means in Northern Ireland.

All of the aforementioned mannerisms and beliefs that are espoused through Paddington about what it means to be British in the twenty-first century have no cultural capital in Northern Ireland. Here, as the reader will no doubt be aware, British Nationalism is vocal, unapologetic, militant, and right-wing. It does not appease, nor does it keep quiet about the problems it faces. Those here who identify as British are proud of their history, culture, and traditions. In many areas of Northern Ireland, especially at this time of year, there are countless marching bands parading through bunting-clad streets. Historical reenactments of events in British history take place, commemorating acts which built the nation. Bonfires constructed in the national colours are topped with icons depicting people perceived to be enemies of Britain, typically Irish flags and images of Irish Nationalist politicians, but more recently controversial sculptures of small boat immigrants.

For many in Northern Ireland, this is their British identity: as they see it, they are sticking up for the honour and integrity of the nation that defended them so vehemently against Irish nationalist terror during the Troubles. This is the kind of Britishness that would make Paddington choke on his marmalade sandwich. Yet, like it or not, it is what British nationalism looks like to people here.

Indeed, Paddington is not at all representative of what it means to be British in the twenty-first century. He may accurately represent the views of the liberal democrat-voting, FBPE-in-Twitter-bio-having, middle-aged middle-managers who appear to be running this country behind the scenes. He does not, however, speak for the vast majority of Britons who believe that current levels of immigration are too high. In Northern Ireland, only a third of people who self-describe as British believe that immigrants are good for the economy and culture. Paddington doesn’t speak for them.

Suzuki’s love of Britain is infectious. There’s no doubt, too, that he is doing a better job than any tourist board in promoting the virtues of the UK. But please, for the sake of places that aren’t London: he should leave Paddington at home.

Comments