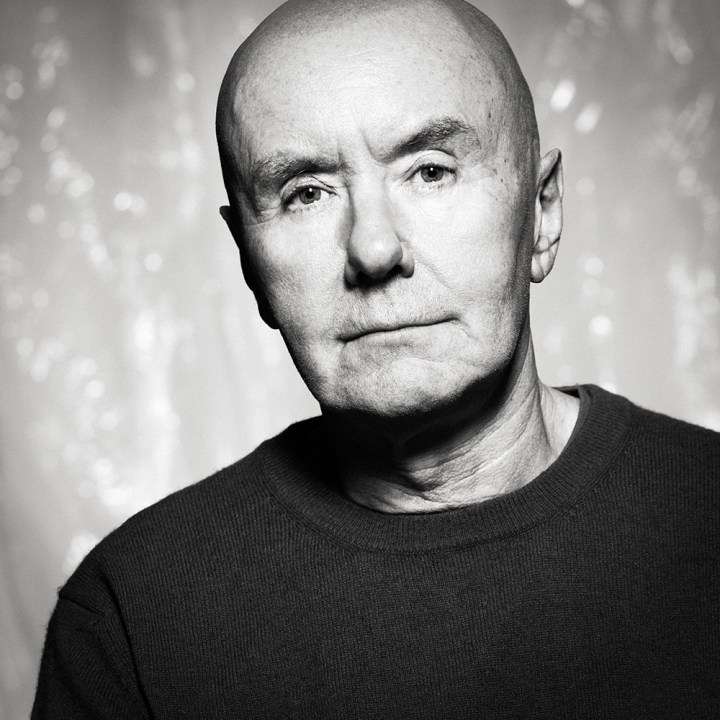

There are 32 years between the publication of Irvine Welsh’s Trainspotting and his Men in Love – a gap roughly equivalent to that between Sgt. Pepper and ‘Windowlicker’ by Aphex Twin. Perhaps three cultural generations. It is disturbing, therefore, to find Welsh still pumping out further sequels to his spectacular literary debut. But whereas that had verbal fireworks, razor-sharp dialogue, superb character ventriloquism and a fearless examination of Scottish moral rot, Men in Love is – let’s be frank – tedious, lazy, pretentious and simply bad writing.

Under the influence of American Psycho, Welsh has had characters narrating their fleeting perceptions since Filth (1998), in the hope that accumulation will create meaning. But where Bret Easton Ellis is satirising the vicious lizard-brain petulance of the 1 per cent, Welsh now simply takes you with the narrator on increasingly pointless journeys. The result is entire chapters that feel redundant and anti-plots that seem to build to something before ending in irritating anti-climaxes. (The Renton-Begbie confrontation in 2002’s Porno was so bad that I wondered whether a refusal to climax was a meta joke.)

Trainspotting vibrated with malevolent vernacular energy, but the prequels and sequels have seen Welsh lose his ventriloquial gift. This was already apparent in Porno, where Nikki’s speech at the end was pure authorial intervention as she tells us What It All Meant. From Skagboys (2012) onwards, Renton, Sick Boy, Spud and even Begbie have been articulating their thoughts in increasingly florid sentences, as if Welsh were trying to impress us with his new-found vocabulary.

But it doesn’t impress. Of course, part of the pleasure of reading Welsh was how he combined the demotic and the cerebral. But the writing in Men in Love can be as clumsy and self-regarding as undergraduate poetry. For instance, Spud thinks that ‘she should pure huv the vocabulary tae express hersel withoot recourse tae foul language’. Without recourse, aye?

The once-fearsome Begbie, meanwhile:

Now he was outside and it was Saturday, drifting into late afternoon, a time Begbie found replete with opportunities for violence. Potential adversaries were out, some since Friday after work. Many of those boys acquiring the delicious bold-but-sloppy combination that would service his chaotic outpourings.

He found them replete, did he? He had chaotic outpourings, did he? And the sex writing – ‘in languid, ethereal movements she groans in soft tones’, for example – is excruciating.

Another key weakness of Men in Love is how many earlier beats it replays. Sick Boy is involved with porn films and pimping; women magically fall under his spell; and he outplays a privileged male competitor (this time his father-in-law, a Home Office civil servant). Renton gets into nightclubs and DJ-ing. Spud is a romantic loser. Begbie is still psychotically aggressive. All of which we’ve seen in Porno, The Blade Artist and Dead Men’s Trousers. The record is stuck.

The heartbreaking thing is there’s a good novel to be written about the punk/smack generation of the early 1980s encountering the ecstasy love-buzz period as the decade progressed. But Welsh has signally failed to tackle any of that. He could have taken them to Ibiza, the Hacienda or Spike Island, or considered the achievements and failures of the Love Generation Mk II. But no. It’s another lazy retread.

The impression one gets from Men in Love is that of Fat Elvis, sweating and unknowingly self-parodic in Las Vegas. Welsh desperately needs an editor with the guts to tell him this schtick isn’t working any more. To quote Melody Maker on David Bowie: ‘Sit down, man, you’re a fucking disgrace.’

Comments