Visitors to the Victoria and Albert Museum’s new storehouse in Stratford’s Olympic Park are being enthralled by an atmospherically lit chamber devoted to the display of one vast and magnificent work of art: Picasso’s 10 metre-high, 11 metre-wide drop-curtain for Le Train Bleu, a popular hit of Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, first seen in 1924. The canvas, for many years rolled up in storage, isn’t strictly the work of Picasso himself: Diaghilev’s scene painter Prince Alexander Schervashidze had meticulously expanded it overnight from a small gouache on plywood known as ‘Two Women Running on the Beach’ (1922), but Picasso was so delighted when he saw the result that he decided to endorse it with his signature on the bottom-left-hand corner.

Cocteau spotted Picasso and corralled him and Satie into a sensational project

This ‘marvel of the 20th century’ – as the critic Richard Buckle rapturously described it – serves as a pendant to an upcoming exhibition at Tate Modern entitled Theatre Picasso. Built on a base of Tate’s own holdings and centred on the masterly painting ‘Three Dancers’ (1925), it also extends to embrace Picasso’s images of ballerinas, bullfights, flamenco and saltimbanques, fashionably complemented with ‘interventions’ by contemporary artists. Documenting it all is a weighty catalogue loaded with concepts currently dominant in academia, drawing on the ‘performative’ notions of the likes of Gilles Deleuze and ‘informed by the perspectives of feminism, colonialism, ecologies and so on’. Don’t let such arcane theorising and vaporous artspeak put you off: Tate Modern’s walls will be showing Picasso at his best, freshly contextualised. (And to be fair to the curators, the catalogue will also contain illuminating essays on the roots of flamenco in the African diaspora and Picasso’s early involvement in anarchism.)

Whether ‘performative’ or not, it is undeniable that Picasso’s art is obsessed by performers: they are ubiquitous throughout his works. In his early years in Barcelona, he painted garish images of cabaret singers and can-can dancers in low smoky dives; during his subsequent rose period, he found a gentler wistfulness in travelling circus folk. Then came his hard-edged experiments with cubism in Bohemian Paris, where in 1915, he encountered the well-connected young man of the moment Jean Cocteau, and a new set of theatrical possibilities opened up.

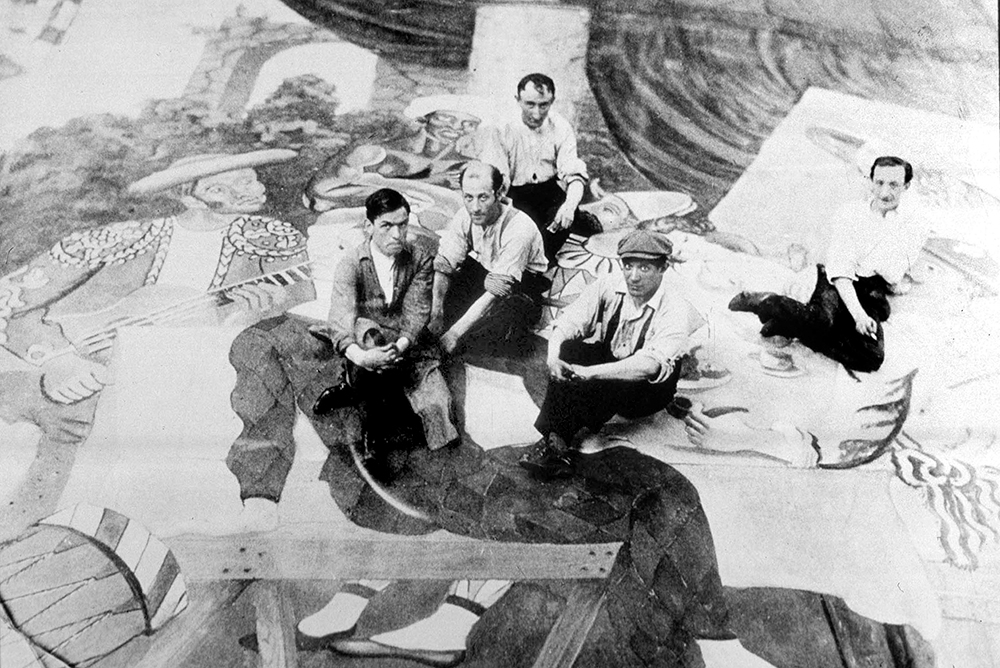

Cocteau had long been hanging around Diaghilev’s circle in the hope of winning a commission for the Ballets Russes. So far he had failed: the great Russian impresario had brushed him aside with the challenge ‘Etonne-moi, Jean’ – the implication being that Cocteau should buzz off until he could come up with something really good. He now had that in hand: he had spotted Picasso, his genius still little appreciated, and corralled him and the composer Erik Satie into a project to create an entertainment that would be both sensational and unprecedented. An étonné Diaghilev duly succumbed, introducing his own protégé, the choreographer Leonid Massine, into the mix.

What this gang of four cooked up was the crazy Parade. Set outside a fairground ticket booth, it featured a conjuror, two acrobats and an American ingénue modelled on Mary Pickford, all vainly trying to solicit customers with their routines. They are overseen by three massive grotesque figures, conceived cubistically: one of them, for example, appeared hidden in a blue, white, green and red box representing a man in evening dress on its front and a house and a tree on its rear. Against a backdrop of higgledy-piggledy skyscrapers, the tone of the action devised by Cocteau was that of inconsequential cartoon farce, but Picasso also painted a richly whimsical front curtain depicting a winged horse and feasting musicians and harlequins.

The productions Picasso designed for Diaghilev served as living billboards for his art

The resulting clash of realist and cubist idioms proved one reason that Parade was scandalously booed at its première in Paris in 1917, and some stiff-necks found its flippancy distasteful at a time when French soldiers were being slaughtered during the catastrophic Nivelle offensive. Yet there were many who fell for it, too. Its free-wheeling originality and wit, heralding the playfulness of dada and surrealism, earn it a place among the defining moments in the development of modernism. It also brought Picasso fame beyond metropolitan coteries: in an age before colour reproduction or mass media, the productions that he went on to design for Diaghilev over the next seven years served as advertisements, living billboards, for his art.

Much to his chagrin, Cocteau was sidelined in the later stages of Parade’s rehearsal, but the bond Picasso established with Diaghilev and Massine would yield further fruit. Le Tricorne, premièred in London in 1919, was a tale of marital jealousy in a rustic Spanish setting evoked by pale ochre and pink flats, with a backdrop of a star-spangled sky and Goyaesque costumes in startlingly vivid scarlet, yellow and black. Picasso personally painted the front drop curtain and attended to every detail of prop and make-up: the entire spectacle was considered ravishingly beautiful and scored instant universal success, sparking a vogue for all things Hispanic.

Immediately after this came the Italianate Pulcinella (1920), to a score for which Stravinsky neoclassically reorchestrated music by Pergolesi. Diaghilev was aghast at Picasso’s early draft of designs for this commedia dell’arte-inspired ballet, tearing up the sheets of paper and stamping on them in a rare display of bad temper. Picasso meekly abandoned his elaborate idea of presenting a baroque theatre inside a theatre and substituted it for two houses on a moonlit Neapolitan street with a view over the bay to Vesuvius – a concept marked, in the words of Douglas Cooper, by ‘an astonishing simplicity’ that showed ‘that Cubism could be happily allied with a mood of unashamed romanticism’.

Pulcinella marks the high point of Picasso’s work for the Ballets Russes. All that followed was a flamenco show, a backcloth for L’Après-midi d’un faune and the drop-curtain for Le Train Bleu (which rose to reveal distinctly feeble décor by the cubist sculptor Henri Laurens – one of Diaghilev’s miscalculations). The odd one out is Mercure, commissioned in 1924 by Diaghilev’s rival Etienne de Beaumont, but briefly imported into the Ballets Russes’ repertory in 1927. Not so much a ballet as a series of tableaux, it reunited Picasso with Parade’s composer Satie and choreographer Massine, and allowed him to give full rein both to his fascination with the imagery of Greek myth and his desire to transcend the limited dimensions of a painted canvas. But the resort to exaggerated caricature, including bulbous female breasts, came over as mere crudity, and the piece was received with either bafflement or hostility. ‘The whole thing appeared incredibly stupid, vulgar, and pointless,’ complained the normally fawning dance critic Cyril Beaumont.

After his involvement in the artistic laboratory of the Ballets Russes had ceased, Picasso contributed little of note to the theatre. By the end of the 1920s his interest in designing for the medium had waned, reviving only vestigially in the early 1960s when he allowed work he had previously made to be adapted for another mythological ballet Icare, at the Paris Opéra. The Tate Modern exhibition doesn’t stop there, however. It interprets the word ‘theatre’ in its widest sense, relating it to the staginess of studio compositions and the artist’s self-dramatised persona. Even if this seems somewhat tenuous, it has certainly provided the curators with a good excuse to show a fine selection of marvellous art culled from a span of Picasso’s immense oeuvre. One obvious link is left unmade, however: it would lead to David Hockney, whose decade designing opera (and a new version of Parade) owes a great deal to Picasso’s pioneering example.

Theatre Picasso is at Tate Modern from 17 September to 12 April 2026. Rupert Christiansen is the author of Diaghilev’s Empire: How the Ballets Russes enthralled the World.

Comments